Betty Skelton…..Aviation’s Sweetheart – September 16, 2022

Before The F-117, And The B-2, There Was Tacit Blue – September 9, 2022

September 9, 2022

We All know About the Lone Eagle but What About Beryl Markham – September 23, 2022

September 23, 2022RN3DB

September 16, 2022

Good Morning,

I hope all is well for everyone and hopefully the weekend will provide sufficient time for everyone to recover from a busy week. For the past few months we have talked a lot about aviation pioneers, and especially those pioneers that made the Wright Brothers successful; however, today I want to move forward in time to talk about Betty Skelton who has the nickname – “First Lady of Firsts.”

I first became familiar with Betty’s accomplishments through the National Corvette Museum. I am a Corvette guy, always have been, and always will be. As a matter of fact, I like Corvettes more than I like airplanes now that I think about it but this article is about Betty and not Robert Novell so let me get back to the business of telling my story.

Betty was the first woman inducted in to the Corvette Hall of Fame as a result of her accomplishments behind the wheel of a Corvette. Betty established a number of speed records on NASCAR’s measured mile at Daytona Beach, Florida, and also represented GM at major auto shows, in TV commercials, and national radio ads. Harley Earl at the GM Tech Center, along with Bill Mitchell, designed a special Corvette for Betty, in 1956-57, which was a translucent gold, and Betty drove the Corvette to Daytona for Speed Week and then paced all the NASCAR races with it in 1957.

A really interesting fact, that is not well known, is that in 1959 she was invited by NASA to become the first woman to undergo the same physical and psychological testing as the first seven astronauts and because she was actively promoting the Corvette line she had GM give all of the original astronauts new Corvettes – A very savvy PR move on her part.

OK, let’s move beyond Corvettes and talk about Betty’s accomplishment as an aviator, and I am going to do that by posting an article, in its entirety, on Betty from the “Women in Aviation Resource Center.”

Enjoy……………………………..

Betty Skelton – Aviation’s Sweetheart

In aviation circles there are few people who are considered “living legends.” Legends are those who have blazed trails and whose glorious exploits, impressive accomplishments and immeasurable popularity has spanned generations.

In an era where heroes were race pilots, jet jocks and movie stars, Betty Skelton was an aviation sweetheart, an international celebrity and a flying sensation. Her career and success could be pages right out of a storybook but even Hollywood couldn’t produce a picture as grand as the real life that Betty Skelton has led.

Betty’s enviable record is still recognized today by pilots, and competitors, and she is frequently referred to as, The First Lady of Firsts. She was the first woman to cut a ribbon while flying inverted and she piloted the smallest plane ever to cross the Irish Sea. Twice she set the world light-plane altitude record (29,050 feet in a Piper Cub, in 1951). The first time Betty broke the record established in 1913 in Germany. She also unofficially set the world speed record for engine aircraft in 1949. Today Betty Skelton holds more combined aviation and automotive records that anyone in history. “I have always been interested in speed,” she said. “It’s pretty fortunate when you can find something you love to do so much and it is also your occupation.” Besides winning the International Feminine Aerobatic Championship for three consecutive years, 1948 – 1950, she received honorary wings from the United States Navy and held the rank of Major in the Civil Air Patrol. She flew helicopters, jets, blimps and gliders, and participated in all U.S. major air events in the forties. Today the very spirit of Betty Skelton and her love and devotion to aviation and aerobatics is bestowed upon the top female in the field with the presentation of the coveted “Betty Skelton First Lady of Aerobatics” trophy.

As a young girl in Pensacola, Florida, Betty watched the Navy Stearmans fly their aerobatic routines from her back yard. She dreamed of someday flying too. Her parents co-owned a fixed base operation in Tampa, Florida so she literally grew up in airplanes. Betty recalls playing with model airplanes instead of dolls and soloed illegally at the age of twelve. She was a commercial pilot at eighteen and a flight instructor by the time she was twenty.

Betty’s real desire was to fly military planes as a ferry pilot in the WASP program. Her flight experience ranked among the best but she was “shot down” because of her age. The minimum was 18 1/2 and at 17 she couldn’t get a waiver. The WASP program would end four months before she reached the appropriate age. In the years while she waited, Clem Whittenbeck, the famous aerobatic pilot of the 1930’s, taught Betty how to do loops and rolls and for her, aerobatics was love at first flight.

“My first aerobatic plane was a real crate!” says Betty, “It was a 1929 Great Lakes that was sluggish and not nearly as responsive as a true aerobatic plane should be.” Its Kinner engine was usually “sick” and she had her share of serious mishaps and narrow escapes flying the old “Lakes.” She even crashed it once.

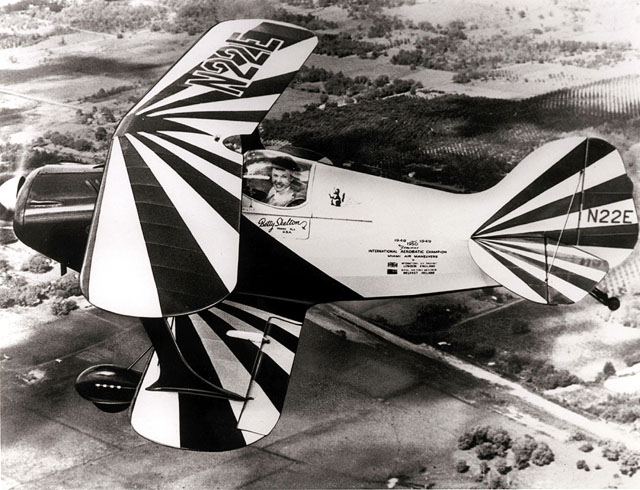

In 1948 she purchased the one and only Pitts Special, an experimental biplane hand-built, and carefully designed by Curtis Pitts himself. It was a single seat, open cockpit aircraft weighing only 544 pounds. Little did she know at the time that she and the Pitts would become a famous team that would soar to new heights. Her plane would become the most famous aerobatic aircraft in the world. Betty would teach the little Pitts a lot of new maneuvers, but not before the airplane taught Betty a thing or two.

With one Feminine Aerobatic Trophy already to her credit, Betty flew her new Pitts Special back to her home base at Tampa’s Peter O’Knight airport. A large crowd of friends and well-wishers gathered to welcome Betty and her new flying machine, and it was on that day she found a suitable name for her new partner.

Upon purchasing the Pitts, the former owner quickly checked Betty out in the plane but neglected to mention a few things about the landing characteristics. Betty made her approach into Tampa and landed nicely. Suddenly, as she brought the Pitts to a stop, it went out of control. She could not have known that at low speeds the plane’s rudder was ineffective and only the brakes would keep her going straight. As she clamored to bring the plane under control she said under her breath: “You little stinker!” The Pitts resented that rejoinder and ground-looped in front of the entire crowd. Nothing but Betty’s pride was hurt but the name stuck. From that moment on they would live forever as Betty Skelton and her Little Stinker.

Betty would practice for hours, sometimes on just one maneuver. She disciplined herself and never strayed from the hard and fast rules that she imposed. One rule was to build an extra margin of safety into all her low level maneuvers. She would compromise for nothing less than an extra ten percent of airspeed or altitude. If she had both, so much the better. This extra margin of safety would keep her out of trouble in the future. With Betty safety always came first. She routinely practiced at an altitude of 3,000 feet unless she was practicing her ribbon cutting, in which case she always had a spot picked out below in case she ran into trouble and needed to make a forced landing.

Betty had two safety belts built into the airplane at different locations in the event one broke loose during a violent maneuver. During practice she placed towels between herself and the safety harness to act like shock absorbers, but they never eliminated all the pressure. As a result, Betty was always bruised. When she worked intensely on her outside maneuvers, the forced pressure of blood to her face would cause Betty to go for weeks with black eyes and splotches on her face. During other maneuvers when the blood would drain from her body, she would experience momentary “red-out.” She slowly built up her tolerance and always knew how far she could push a maneuver and still stay in control.

Soon Betty and Little Stinker worked as one. Her movements telegraphed calm and confidence and her little friend, listening to her thoughts, reacted as an extension of Betty’s body, diving and looping to her every command.

The maneuver Betty is best known for is the inverted ribbon cut. This involves cutting a ribbon strung between two poles, ten feet from the ground, upside down. You could count the number of men on one hand that could do the stunt, and being the best meant that Betty had to learn how too. Her friends tried to talk her out of attempting the stunt because it was a dangerous maneuver that allowed for no margin of error, but Betty was determined. She would be successful at becoming the first woman to complete the feat but with near fatal results.

Betty promised her friends she would attempt the stunt scientifically, making many practice runs until she felt comfortable. She would start with a high altitude, line up the poles, roll upside down and go lower and lower until she got a feel for it. Betty’s first pass was deliberately high but right on target. Feeling confident, she set up to cut the ribbon on her second attempt, only on this try the Pitts’ engine quit just as she rolled upside down. She was only a few feet above the pavement.

Betty’s ten percent rule saved her life that day. The extra ten percent in airspeed enabled her to execute a half outside snap-roll and bring the plane and herself down to safety. An inspection of the fuel injection system found that the engine’s injector jets were clogged with dirt. After a simple cleaning her Little Stinker was as good as new.

Being number one meant Betty had to work twice as hard as everyone else. Perfecting the artistry of aerobatics and taking her routines to the level of flawless perfection was a skill Betty worked at constantly. Betty attributes her success in the sport to having had the coolness of a champion bullfighter, the fighting spirit of a cornered cobra and the dedication of a priest.

One of the hardest things about flying the aerobatic circuit was enduring the pain of watching many friends die. Each fatality occurred while trying to out fly Betty or while trying to imitate maneuvers that only she could do in her Pitts. (Death was a constant reminder that all aerobatic pilots fly in the shadow of death.) “At times it felt like a waiting game,” says Betty, “wondering who would be next.” Betty looked on death as one of the risks of the business. “Learning to fear death without actually being afraid was something you had to do to make it through.”

Betty didn’t just “luck” into her accomplishments and achievements because of her good looks, although she was every bit the glamour gal that the press made her out to be. Betty didn’t believe in luck, good or bad, just great timing. Betty has, however, become partial to the number “2” over the years.

Betty first laid eyes on her little Pitts on the 2nd of the month. It was serial number two and the aircraft registration number was 22E, (a number that is still reserved for Betty today.) Even the old Taylorcraft she first soloed was NC 22203 and her Great Lakes was numbered NX 202K. Being born at 2:00 a.m. and wearing Channel No. 22 perfume is probably just a coincidence, but number “2” would have special meaning to Betty as the years and her career flew by.

Besides setting altitude records and flying aerobatics, Betty felt the need for speed and loved to race. “Some of my fondest memories are of the flying at the Cleveland Air Races in the late forties.” Betty remembers, “Every big name pilot in the country would be at the races, all the old gang, and it was easy to get caught up in all the excitement.”

Being a champion meant Betty was always in demand and maintaining the hectic schedules was physically exhausting and emotionally draining. Air shows and appearances were scheduled one after another, sometimes three in the same day and all in different cities. Betty’s life was anything but normal and she tired of her nomadic lifestyle. She realized early that it would be impossible to handle a career as well as a family. “During those years more than one engagement ring was returned.”

With all the accomplishments Betty had made in aerobatics, there didn’t seem much left for her to do. For all the fame and glory, there was little money to be made in the sport Betty loved so much. It was no secret, flying was an expensive undertaking and there weren’t many alternatives for women in aviation. She had been born too late to qualify for the military WASP program and too early to try for the airlines. Staying in aviation would have meant going back as a flight instructor or flying at a fixed base operation, “hardly a suitable challenge.” So on October 2, 1951, at the age of 26, Betty retired from professional aerobatic flying.

Although Betty would leave her first love of flying, she would be instrumental in forever changing how women were viewed in the competition level of aerobatics. She challenged the Professional Race Pilots Association and made changes that today allow women to race in closed course pylon races with the men. This set up a chain reaction that would open many doors to women at the competition level of aerobatics.

As for her Little Stinker, it was enshrined in the Smithsonian’s Air and Space Museum on August 22, 1985. “It is tremendously gratifying to know that children may see the tiny plane for decades to come and hopefully be inspired and seek a future in the sky and space.”

Being a person who thrived on challenges and with the open road ahead, it seemed only natural that Betty moved on to auto racing. Her records in this field would become as impressive as those in her aviation career. Betty broke the world land speed record for women four times, and became the first woman to officially drive a vehicle over 300 mph, (315.72 to be exact)! She won nine sport car records for speed and acceleration, and became the first woman test driver as well as the first woman to drive an Indianapolis race car. She toured for the National Safety Council, appeared in national advertisements and TV commercials and co-wrote and produced an award-winning motion picture movie entitled, “Challenge.”

Betty was inducted into the Florida Hall of Fame in 1977, The International Automotive Hall of Fame in 1983, The International Aerobatic Hall of Fame in 1988 and The Tampa Bay Walk of Fame in 1991. Betty married Donald Frankman, a TV director/producer, on New Year’s Eve in 1965. They make their home in Florida where they own a real estate business and consider themselves semi-retired. As a woman who has set more combined aviation and automotive records than anyone in history, Betty can still be found flying in her airplane or driving her red Jaguar, but now it’s purely for pleasure.

When Betty decided to fly Little Stinker she shared with her little friend her beliefs. “If you are to fly with me you must believe in yourself. Pay no attention to what others say, what they think, what they do. Let your free spirit take you where you will, and when it falters, let your soul demand that you not give up, but only aspire to climb higher and higher.

“As you soar into the heights, never forget the others or look down upon them. Remember, you were once there and needed help, understanding, and love. Direct your free spirit to helping your fellow man…and you will know heaven on Earth.

“Never believe your own press, nor take your accolades too seriously. It matters not what you did yesterday. Only what you do today, and tomorrow, is meaningful to your freedom and spirit.

“Challenge and perfection is the greatest gift of life. Embrace it and use it well. To turn your back on the challenge of perfection is to close the door on your spirit, your freedom… your very existence.

“It is not easy to be the best. You must have the courage to bear pain, disappointment, and heartbreak. Our dedication must help lift the other up when one of us is down. You must learn how to face danger and understand fear, yet not be afraid. You must establish your goal, and no matter what deters you along the way, in your every waking moment you must say to yourself, `I can do it.'”

Betty died at the age of 85 and below is part of an article from the NY Times, as well as the link, should you want to read the article in its entirety:

Betty Skelton, Air and Land Daredevil, Dies at 85

(DENNIS HEVESI

The “inverted ribbon cut” was one of Betty Skelton’s most daring maneuvers, in which she flew her single-seat, open-cockpit biplane upside down at about 150 miles per hour, maybe 10 feet above the ground, and sliced through a ribbon stretched between two poles.

In a race car, Ms. Skelton set women’s land-speed records; in one 1956 event she hit 145.044 m.p.h. in her Corvette on the sand flats of Daytona Beach, Fla. (The men’s record at the time was just 3 m.p.h. faster.)

Whether in the air or on land, Ms. Skelton, who died on Aug. 31 at the age of 85, was a celebrated daredevil who shattered speed and altitude records. She was a three-time national aerobatic women’s flight champion when she turned to race-car driving, then went on to exceed 300 m.p.h. in a jet-powered car and cross the United States in under 57 hours, breaking a record each time.

“In an era when heroes were race pilots, jet jocks and movie stars, Betty Skelton was an aviation sweetheart, an international celebrity and a flying sensation,” Henry Holden wrote in his 1994 biography, “Betty Skelton: The First Lady of Firsts.” Her “enviable record,” he added, “is still recognized today by pilots and competitors.”

She also broke gender barriers.

“Betty proved that women were capable of professional aerobatic flight competition,” said Dorothy Cochrane, curator of general aviation at the National Air and Space Museum of the Smithsonian Institution, where Ms. Skelton’s Pitts S-1C plane, Little Stinker, hangs, upside down, near the entrance. “She paved the way for women like Betty Stewart, Mary Gaffney and Patty Wagstaff, who in 1991 became the first woman to win the national championship competing against both men and women.”

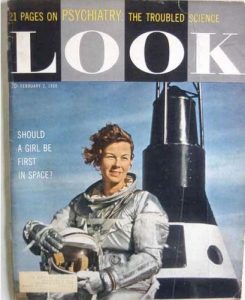

In 1960, Ms. Skelton appeared on the cover of Look magazine, in an astronaut’s flight suit, next to the headline: “Should a Girl Be First in Space?”

Ms. Skelton, who never grew beyond 5-foot-3 and about 100 pounds, acquired her passion for speed as an 8-year-old redhead perched on her porch in Pensacola, Fla., finding herself riveted by the pilots from the nearby Navy base swooping overhead. Entering competitive flying, however, she was matched against only other women, winning the United States Feminine Aerobatic Championship in 1948, 1949 and 1950.

While the gender divide has disappeared — men and women both compete in what are now known simply as the United States National Aerobatic Championships — the maneuvers required to win the title are essentially the same as those in Ms. Skelton’s day.

One is the hammerhead, in which the pilot soars vertically to a certain altitude, snaps the plane 180 degrees and roars straight down before pulling up. Judges also rate precision in the triple snap roll, which requires three horizontal 360-degree rolls while maintaining altitude. Another feat is the outside loop, a circle flown around a point in the sky with the cockpit facing outward.

“Difficult in an open-air cockpit like Betty’s Pitts,” Ms. Cochrane said. Difficult, too, on the day in 1949 when Ms. Skelton became the first woman to perform the inverted ribbon cut at an airfield in Oshkosh, Wis. In an oral history for the National Aeronautics and Space Administration in 1999, she recalled how risky the maneuver was.

The first time she tried it, she said, “I misjudged slightly and flew underneath the ribbon, which put me even closer to the ground.”

“I never made that mistake again,” she added.

During six years as a competitive pilot, Ms. Skelton set a series of women’s records for light planes, among them reaching 29,050 feet in a Piper Cub at an airfield in Tampa, Fla., in 1951. She traveled the air-show circuit around the country, performing what she declined to call stunts.

Have a good weekend, enjoy time with friends and family, protect yourself, your profession, and the “Third Dimension” for those who will follow in your footsteps.

Robert Novell

September 16, 2022