World War II and The Piper Cub

Upset Prevention and Recovery Training

April 20, 2014

Aviation Wisdom From the Past

April 28, 2014Robert Novells’ Third Dimension Blog

Good Morning and Happy Friday. Today I want to go back and talk about an airplane that was an essential tool in WWII and was produced in larger numbers than any other airframe. The Piper Cub, military designation L-4, proved itself to be a wild card in the winning hand that brought victory to the U.S. Forces.

To begin I want to give you an overview of William Piper Sr. and then follow that with the specifics on the Piper L-4.

Enjoy………………………….

William Piper, Sr.

(Inducted in to the Aviation Hall of Fame in 1980)

Piper realized that aircraft sales were directly related to the number of people who knew how to fly. So he set up a flying school in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, at his manufacturing plant adjacent to the Lock Haven airport. Students who wanted to learn to fly paid their transportation, lodging and meals and Piper taught them to fly for $1 an hour which included the cost of the airplane and instructor. This low instruction cost also applied to his employees. At one time one out of every 90 persons in Lock Haven held a pilot’s license. It had a positive impact on the business because as long as the kids wanted to fly, they would build a good product.

William Thomas Piper, Sr. was born in 1881 at Knapp Creek, a small village in New York. There his father dabbled both in dairy farming and in the promising crude oil business.

By the time he was eight, young Bill Piper was already cast in the mold of rural America, milking cows and walking several miles to a one-room country school. At the age of nine he introduced himself to the oil business when he assisted in the grimy task of repairing well pumps. When family finances improved, the Piper family moved to Bradford, Pennsylvania.

In 1898, when war hysteria swept the country after the sinking of the battleship Maine, Piper fibbed about his age and joined the Army during the ensuing Spanish-American War. He participated in one brief skirmish with a poorly equipped and disciplined enemy platoon. After the war, Piper enrolled in the mechanical engineering program at Harvard. There, he starred in a track meet with Yale where he threw the hammer almost 129 feet. After graduating from Harvard in 1903, with honors, he worked in the building construction field. He also sang in a church choir, where he met his eventual wife, Marie van de Water. After they were married, they returned to Bradford, where Bill took up his father’s oil business, and with a partner formed the Dallas Oil Company. During World War I, Piper served as a captain in the Army Corps of Engineers. After the war he returned to the oil business, which gradually grew less profitable and presented a problem with a wife and five children to support.

Bill Piper’s entry into aviation was completely unplanned. It began after C. Gilbert Taylor, a self-taught airplane designer, built a small monoplane. Taylor convinced Bradford’s community leaders to pledge $50,000 toward building a facility to produce it at the town’s airport. Piper’s business partner, in his absence, pledged Piper to invest $400 in the new business and later told him: “Bill, you’re in the airplane business.” William Thomas Piper had very little knowledge about aviation when he invested $400 in the newly-created Taylor Brothers Aircraft Corporation, and was elected to its board and named treasurer. The Great Depression descended upon the nation and, when few Taylor biplanes were sold, the company went bankrupt.

In the ensuing public sale, Piper’s lone bid of $761 made him sole owner of the company. Though times were hard, his company designed several low cost planes. Among them was the “Cub”, a small monoplane that was destined for aviation history. It proved to be a dream to fly, and its price of $1,325 fit Piper’s philosophy of giving the most airplane for the dollar. Piper also surprises nearly everyone when he learned to fly a Cub at the age of 50.

But then skidding sales in 1932 caused him to seek out prospective dealers all over the country, pushing the Cub’s appealing low cost and free flying lessons. By 1935 he had brought the company well into the black, as the Cub enabled thousands to experience the thrill of flying for the first time. Piper constantly promoted Cubs with dealers and at exhibitions of all kinds. A Cub also stole the show at the air races, when “Mike” Murphy landed one atop a speeding car.

After the prettied-up J-2 Cub was introduced, increased sales in 1937 required a second production shift. Unfortunately, a fire swept the plant, causing great losses. But Piper soon had production rolling again. Later, his three sons: Thomas, Howard and William, help him convert an abandoned silk mill in Lock Haven, Pennsylvania, into an airplane factory, and reorganize the company into the Piper Aircraft Corporation. Soon the dolled-up Piper “Cub Sport” was introduced. By this time, Cubs were setting all kinds of records. One even stayed aloft 218 hours.

As the threat of war hung over Europe, President Roosevelt inaugurated a college pilot training program that used Cubs to turn out thousands of pilots. Even the First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt went aloft in a Cub to promote this most ambitious program. Meanwhile, Piper introduced the handsome J-4 “Coupe” and the more powerful J-5 “Cruiser”. By then, Pipers represented a third of all civilian aircraft in the United States.

Piper’s big break to demonstrate the military potential of his planes came during the 1941 Army war games. At these games, Cubs directed armored columns and artillery fire from the air, and acquired the military nickname “Grasshopper”. Only hours after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Piper said of his Cubs: “They will have their place in the war.” His statement proved correct, for the Army Air Forces quickly ordered 1500 Grasshoppers, and training of field artillery pilots began, giving birth to Army ground force aviation in which a single man in a tiny plane could influence the course of battle.

Improved Grasshoppers soon flowed from Piper’s factory, including ambulance planes for the Navy, and glider trainers. The Grasshoppers first went into combat during the invasion of North Africa, when three took off from a carrier for reconnaissance flights. After this, they operated with the Army in every campaign and on every front of the war. In the invasions of Sicily and Italy, Grasshoppers really won their spurs directing Naval fire over the beaches, as General Mark Clark used his Grasshopper to inspect the seething battlefront at Anzio. In the drive up the Italian boot, Grasshoppers showed the way.

In the invasion of Europe, Grasshoppers directed broadsides against fortifications along the beaches of Normandy. Then, as the Allies swept inland, pilots added bazookas to their Grasshoppers to knock out tanks and entrenched artillery. Meanwhile, Eisenhower inspected the raging battle areas in his personal Grasshopper, as Patton’s tanks raced into the heart of Germany.

In McArthur’s struggle in the Pacific, Grasshoppers went ashore to direct artillery against Japanese strongholds and provided vital support in campaigns from New Guinea to the Philippines. In the end, Piper’s planes played a vital role in winning the war, having helped train four out of five American pilots, and revolutionizing almost every aspect of land warfare.

When peace came, prospects for light planes seemed bright, as Piper’s “family cruiser” is added to the pre-war “Cub” and “Cruiser”, followed by the “Super Cruiser”. Then, as the post war boom fade, the low-cost, stripped-down “Vagabond” was added to spur sales. Soon the Piper “Pager” was introduced to the line, as is the popular “Super Cub”, which replaced the old faithful Cub after 20,000 had been built.

In the early 1950s, Piper made Grasshoppers which it produced for the Air Force and NATO countries. Also Piper’s first crop duster was introduced for the agricultural market. Meanwhile, the newly-created “Tri-pacer 135″ became an instant success. In 1954, the twin engine “Apache” became the cornerstone of Piper’s postwar growth, meeting the needs for an above-the-weather airplane, and amazingly, at the age of 73, Bill Piper soloed in an Apache.

In 1957 Piper opened a new plant in Florida, where the “Cherokee”, the world’s best selling low-wing monoplane, is produced, along with the high-styled “Comanche”. Then came the “Colt” trainer and the “Pawnee” agricultural plane, followed by the “Aztec”, one of which was purchased by the Arthur Godfrey Foundation for the African Research Foundation in Kenya. Next came the “Twin Comanche”, as well as the luxurious pressured “Navajo” for the executive market, and finally the “Seneca”, the world’s lowest-priced multi-seat twin.

In the decade of the ’60s, Piper had a third of the light plane market and new plants had been added in Pennsylvania and Florida, while engineering and administration buildings were dedicated to carry on the company’s heritage of continuing innovations and quality and building the very best airplane for the dollar. In 1968, Piper finally relinquished his presidency to his son, Bill, while he retained board chairmanship.

His death in 1970 brought to an end a career that added immeasurably to the role of the private airplane in the great transportation revolution.

Piper L-4 Grasshopper

(Nicknamed the “”Maytag Messerschmitts”)

(Italy, 1943. A.W. Schultz, artillery spotter plane pilot of Piper L-4 confers with an enlisted tank commander in a temporary field. Piper L-4’s were wartime “Cubs,” built by the thousands for liaison and artillery spotting.)

(Italy, 1943. A.W. Schultz, artillery spotter plane pilot of Piper L-4 confers with an enlisted tank commander in a temporary field. Piper L-4’s were wartime “Cubs,” built by the thousands for liaison and artillery spotting.)

“The Piper L-4 Grasshopper of WW2 was the military version of the highly popular pre-war J3 Cub, by which name it was more widely known to service personnel. Of the 5,500 L-4 variants produced between 1942 and 1945, some went to liaison squadrons and of the USAAF, but the vast majority went to US Army Ground Forces, for use as Air Observation Posts (Air Ops) with the Field Artillery. In both air and ground forces, the L-4 was also used as a flying Jeep, among other things carrying priority mail and personnel between HQs and command posts. Its Continental engine produced only 65 hp, yet the L-4′s excellent short field performance enabled it to operate from the smallest of improvised airstrips, including roads, adjacent to command posts.

Unlike most other combat aircraft, the L-4 was unarmed and unarmored. It was one of the smallest aircraft of WW2 and, with a cruising speed of only 75 mph, it was the slowest. Nevertheless, it has been claimed that a single L-4, directing the fire power of an entire Division, could bring a greater weight of explosives to bear on a target then any other aircraft of that period. With the exception of the atomic bomb carrying B-29 Superfortress, no other single aircraft had the destructive capability of the diminutive L-4.

It was most widely used in Europe, where more than 2,700 served with the Field Artillery, and of these nearly 900 were lost through enemy action or in accidents. Of those that survived the war, about 150 were shipped back to the US, most of the remainder eventually being sold to civilian purchasers in Britain, France, Switzerland, Denmark and elsewhere in Europe. More than 60 years on many of these are still flying with, in recent years, an increasing number being restored to their original military configuration and markings.

So successful was the L-4 that it’s military use continued on through to the Korean War, and as recently as Vietnam. Today, hundreds still fly on as civilian light aircraft, some as meticulously restored military aircraft and others in colorful civilian schemes

(A Piper Cub snags a message from a patrol on New Britain’s north coast during WWII)

(A Piper Cub snags a message from a patrol on New Britain’s north coast during WWII)

Piper developed a military variant (“All we had to do,” Bill Jr. is quoted as saying, “was paint the Cub olive drab to produce a military airplane”), variously designated as the O-59 (1941), L-4 (after April 1942), and NE (U.S. Navy). The L-4 Grasshopper was mechanically identical to the J-3 civilian Cub, but was distinguishable by the use of a Plexiglas greenhouse skylight and rear windows for improved visibility, much like the Taylorcraft L-2 and Aeronca L-3 also in use with the US armed forces. Carrying a single pilot and no passenger, the L-4 had a top speed of 85 mph (137 km/h), a cruise speed of 75 mph (121 km/h), a service ceiling of 12,000 ft (3,658 m), a stall speed of 38 mph (61 km/h), an endurance of three hours, and a range of 225 mi (362 km). 5,413 L-4s were produced for U.S. forces, including 250 built for the U.S. Navy under contract as the NE-1 and NE-2.

All L-4 models, as well as similar, tandem-cockpit accommodation aircraft from Aeronca and Taylorcraft, were collectively nicknamed “Grasshoppers”, though the L-4 was almost universally referred to by its civilian designation of Cub. The L-4 was used extensively in World War II for reconnaissance, transporting supplies, artillery spotting duties, and medical evacuation of wounded soldiers. During the Allied invasion of France in June 1944, the L-4’s slow cruising speed and low-level maneuverability made it an ideal observation platform for spotting hidden German tanks waiting in ambush in the hedge-rowed country south of the invasion beaches. For these operations the pilot generally carried both an observer/radio operator and a 25-pound communications radio, a load that often exceeded the plane’s specified weight capacity. After the Allied breakout in France, L-4s were also sometimes equipped with improvised racks, usually in pairs or quartets, of infantry bazookas for ground attack against German armored units. The most famous of these L-4 ground attack planes was Rosie the Rocketeer, piloted by Maj. Charles “Bazooka Charlie” Carpenter, whose six bazooka rocket launchers were credited with eliminating six enemy tanks and several armored cars during its wartime service.

(L-4 Piper Cub, France. Nov. 1944.)

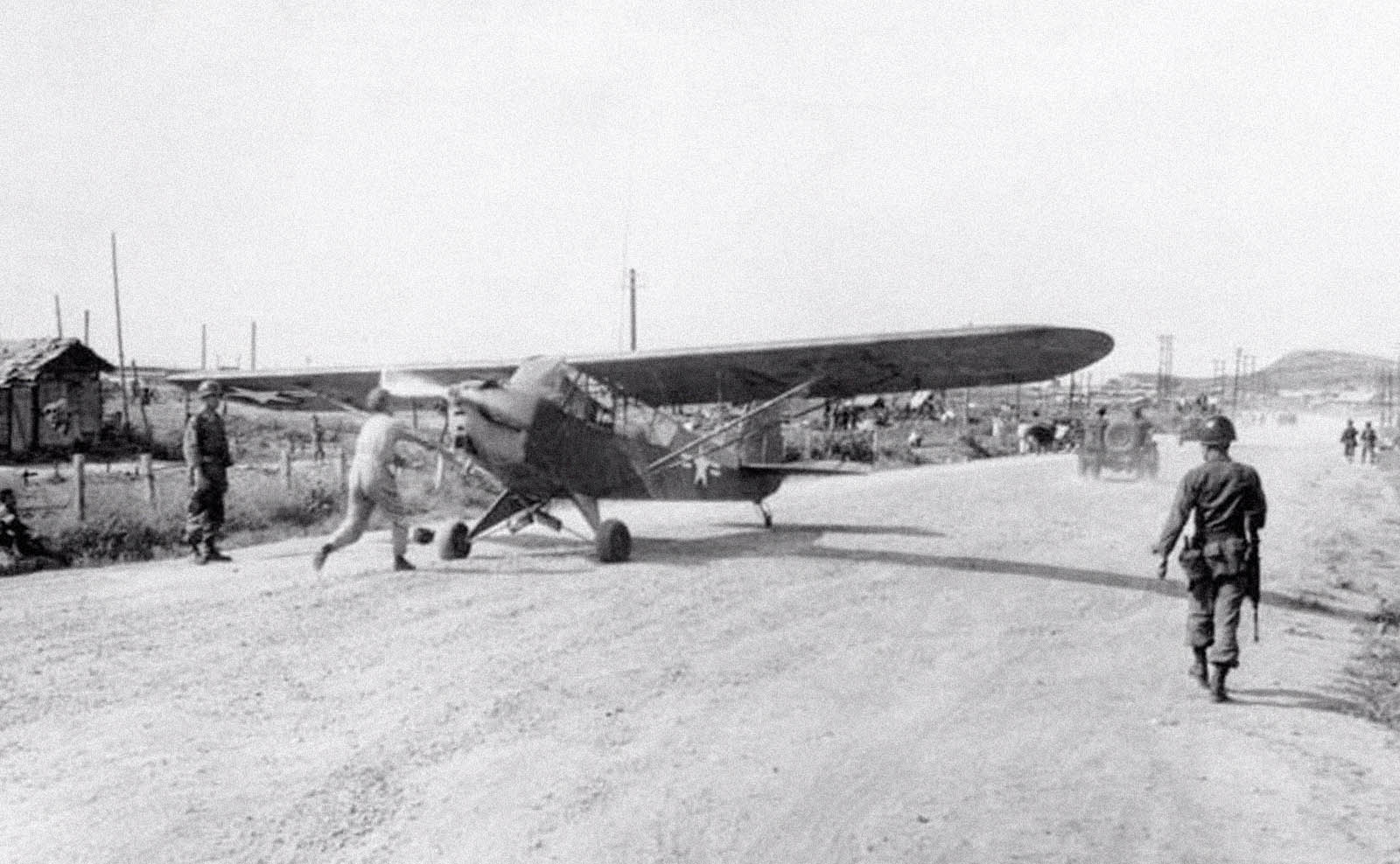

(A Piper L-4 Grasshopper gets hand-propped to start near the front lines.)

(A Piper L-4 Grasshopper gets hand-propped to start near the front lines.)

(Major Charles “Bazooka Charlie” Carpenter, US Army, poses with his Piper L-4 Grasshopper, “Rosie the Rocketeer”. Photo Credit: Mrs. E. Carpenter)

(30th Infantry Division L-4 Grasshopper – January 1945)

When allied forces were planning the invasion of Sicily they needed a way to have the L-4 Grasshoppers participate because of their effectiveness at setting up artillery strikes; however, the range of the L-4 made it impossible for them to fly from allied bases so they built an aircraft carrier just for the Grasshopper. They converted a Navy LST into a mini carrier and aboard each LST there were able to carry four aircraft. The LST was fitted with a flight deck made of timber and pierced metal runway mats and the usable length of the area for take-off was 12 feet wide and 216 feet long.

A very interesting fact about the L-4, and LST operations, was the introduction of the Brodie Device. A cable was suspended between two outriggers mounted to the side of a LST. Dangling from the setup was a harness with a loop that could slide down the cable. The plane would be suspended from the harness, the pilot would climb a rope ladder to the cockpit, apply full power, and the plane would fly down the cable. When it reached the end of the cable, the plane would detach from the harness and take flight. To “land,” the pilot would fly the plane into the harness, where it would catch on a hook mounted on the top of the wing. The plane would then slide down the cable until it hit the end and come to a swinging halt. It would then be brought onboard, serviced and be readied for another flight. The video below shows how the system worked.

I hope everyone had a good week and the weekend will provide all of us with a little time away from work and aviation. Enjoy time with friends, and family, and remember life is short. Take some time to enjoy the world around you.

Robert Novell

April 25, 2014