If Amelia Earhart was Considered the “First Lady” of Aviation Who was Considered Second? – November 14, 2014

Aviation Wisdom From the Past – November 10, 2014

November 10, 2014

Dell Smith, CEO of Evergreen International, Has his Final Flight – November 17, 2014

November 17, 2014Robert Novells’ Third Dimension Blog

November 14, 2014

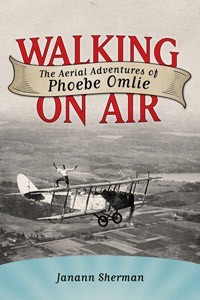

Good Morning and welcome to the 3DB. This week I want to introduce you to a lady whose accomplishments were second only to Amelia Earhart. Aviation pioneer Phoebe Fairgrave Omlie was once one of the most famous women in America. In the 1930s, her words and photographs were splashed across the front pages of newspapers across the nation and the press labeled her “second only to Amelia Earhart among America’s women pilots.” Her accomplishments were many, her contribution to aviation, as we know it, is indisputable, and her life ended tragically in a hotel room at the age of 73. Come with me now as we look back at a part of aviation history that most have forgotten, or never knew.

Enjoy……….

Phoebe Fairgrave Omlie

Aviation pioneer Phoebe Fairgrave Omlie, a contemporary of more famous women flyers like Amelia Earhart, Jacqueline Cochran and Florence “Pancho” Barnes, began her career in the early 1920s when barnstorming was one of the few ways to make a living by flying. She progressed beyond this daring and dangerous aspect of aviation to become one of the field’s most ardent supporters and innovators, a central participant in the move to legitimize and eventually bureaucratize commercial and private aviation in America.

She contributed much of it through her work in the federal government – working with the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and the Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA). Throughout her career, Phoebe used her influence to give other women a chance to prove themselves as capable as men.

Phoebe Fairgrave was born in Des Moines, Iowa in 1902. One day just before her high school graduation, she saw her first air show and fell in love with aviation at first sight. She thought about it; she dreamed about it. She began hanging out at the local airfield, begging the manager until he finally agreed to let one of his pilots take her up for a ride. The pilot’s instructions were to give the girl “the works” – a few loops, maybe a nosedive or two – and get her good and sick. Then maybe she would leave them alone. But the pilot’s efforts to discourage Phoebe were counterproductive, to say the least. She loved it!

Not long after, Phoebe showed up at the airfield with a small inheritance from her grandfather and bought herself an airplane, a Curtiss JN-4D, a “Jenny.” Then she dropped into the local offices of the Fox Moving Picture Company and proposed a bold deal to recoup her investment: Fox could film her wing-walking and making parachute jumps. Phoebe came away with a contract to do stunts for such Fox films as the Saturday matinee serial, The Perils of Pauline. Then she hired a young pilot to fly her Jenny for her. He was Vernon Omlie, a 25-year-old veteran of the Great War. He’d been a military flight instructor and dreamed of making his fortune in aviation. In the meantime, the best he could do was fly for the Curtiss Company for $25 a week. After working for Phoebe for a few weeks, Vernon quit his job with Curtiss to become her personal pilot.

In 1920, there were few opportunities for men in aviation and fewer still for women. So Phoebe did the only things she thought she could do: she learned to walk wings, hang by her teeth below the plane, dance the Charleston on the top wing, and parachute. After a couple months of intensive practice, the Phoebe Fairgrave Flying Circus was born. It was the first flying circus owned by a woman.

The thrill show featured the daring Phoebe, wearing riding breeches, a silk shirt, a goggled leather helmet and basketball shoes with suction soles. Once airborne, Phoebe would climb to the top of the upper wing, the wind whipping her clothes, and ride there while Vernon put the plane through a couple loops. She told the press that wing-walking wasn’t much different than climbing up on a table: “You just shimmy up the strut, grab hold of something on the top wing, throw your knee up there, and climb up.”

Phoebe had a special mouth-piece attached to the end of a rope, which she gripped between her teeth as she dangled and twirled in the plane’s slipstream while Vernon swooped low over the crowd. The showstopper, though, was her own invention: a double parachute drop.

The folded parachute was tied to a wing strut. She would crawl out on the wing, put on her harness and jump, the chute opening as she fell. To keep the lines from tangling, the parachute had been interleaved with newspapers. A safety precaution, it was also a crowd pleaser as the newspapers fluttered out like confetti. Once free of the plane, she would cut the lines of her chute loose and free fall. With the crowd holding its breath – thinking her chute had failed- Phoebe would wait until the last possible minute, then pull the cord on a second chute just in time to prevent her descent to certain death.

In many ways, it’s remarkable that Phoebe survived the 1920s, given the chances she took. After a year of so, she and Vernon teamed up with an accomplished stunt flier named Glenn Messer. Phoebe had ideas for newer and tougher stunts; one of them involved changing from plane to plane in the air. She talked Messer into working with her on it. They found a barn in Iowa that had a central runway from end to end. They rigged a trapeze bar hung from the rafters with Messer hanging by his knees and extending his hands. Phoebe stood on the seat of an old buggy as Vernon piloted the team of horses. As Vernon drove the buggy through the barn, Phoebe would grasp Messer’s hands and be pulled up alongside him on the trapeze. Gradually they increased the speed of the horses to a fast trot until she could connect with Messer on every pass. When they had it perfected, they alerted Fox who sent along a camera crew to film it. There were three planes: the upper plane for Messer, Vernon flew the lower plane, and the movie man was in the third.

Messer was hanging from the axle of the upper plane, hands down, ready to grasp Phoebe’s hands, as the two pilots jockeyed into position, trying also to get in a good position for the camera. Suddenly the lower plane hit an up-draft. Phoebe, standing near the right wing tip of the upper wing on the lower plane, with her toes hooked under two guy wires, saw the upper plane’s propeller coming rapidly toward her. She dropped to her knees, reached under the leading edge of the wing, and grabbed a strut. Then she flipped forward and over the edge and shinnied down to the lower wing, safely out of the range of the whirling prop. The turbulent air continued for a few moments, and the propeller of the upper plane sliced into an aileron of the Omlie plane. Fortunately, Vernon was able to land safely and quickly fixed it.

The movie people were still eager for a picture, so they went up and did it all again, this time successfully. Talking it over later, they agreed to make the stunt a bit less dangerous. After that, Messer hung by his knees from the lowest rung of a 20-foot rope ladder to grab Phoebe’s hands, leaving a margin of unoccupied air between the planes. The act became one of the most spectacular and exciting for the Phoebe Fairgrave Flying Circus.

Thousands would come out to see Phoebe’s show, but it was difficult to ensure that all of them paid to see it. The real money was made in encouraging the crowd to take rides at $5 or $10 a trip. It was a tough way to make a living and sometimes the Phoebe Fairgrave Flying Circus would make less than $10 profit a week.

Phoebe and Vernon headed south, hoping to stay one jump ahead of the coming winter weather. By December, they landed in Memphis, where Phoebe spent much of the winter doing speaking engagements about her life in aviation and in the movies.

Phoebe married her pilot in February 1922 and changed the name on the side of her plane to read the Phoebe Fairgrave Omlie Flying Circus. But they continued to struggle. The circus needed to do something spectacular to get the publicity they could not afford to buy.

They came up with the perfect stunt, and on July 10, 1922, Phoebe Omlie was ready. Vernon lifted the plane’s nose and climbed steadily to over three miles up. Then Phoebe crawled to the end of the wing, strapped on the parachute, stood up, hesitated a moment, and jumped. To her dismay, the chute did not open properly in the thin air, and she was in free fall for at least the first 5,000 feet. When she reached the ground a few minutes later, she was a world record holder for a woman’s parachute jump at 15,200 feet. She had gotten sick on the way down, she told reporters, adding, “It was terrible; I never want to try it again.” But there were few things Phoebe would not try at least once.

Phoebe’s flying circus continued for several more summers, but Vernon was eager to settle down and build himself a business around aviation. Memphis was warm, it had no aviation facilities, and he saw that as opportunity. He set up operations first in the middle of a horse track and began offering rides and lessons. He and Phoebe put on shows for the locals. Gradually the Omlies attracted and trained a group of flying enthusiasts who eventually built Memphis’s first real airport.

Vernon was happy to settle down. But Phoebe still craved excitement. She gave up wing-walking and took up piloting. In 1927, she became the first woman to receive a transport pilots license and the first woman to earn an airplane mechanics license. In 1928, when Vernon moved his fixed-base and charter operation to the new Memphis Municipal Airport, Phoebe won new fame on her own. She was flying for the Mono Aircraft Company of Illinois, builders of monocoupe racers. They provided the planes, and she provided the publicity. In the summer of 1928, she took her little 65-hp monocoupe up to an astonishing 25,400 feet, trying to set a new altitude record. She was still climbing when a spark plug blew out and the main oil line gave way. The spraying oil blinded her and she began fumbling with her oxygen mask, gasping for breath because of the leanness of the oxygen mixture. Almost unconscious she swung the plane once around the field and landed, then collapsed. A physician was waiting when she landed and hurried to check her. Coming to, she remarked, “I feel all right now. I can make the attempt again if I need to.” She didn’t need to-she had set a new world altitude record for women and light aircraft.

Her real passion was air racing, and during the late 1920 she entered dozens of races. She finished first or in the money most of the time. In 1928, she was the only woman competitor in the National Reliability Air Tour for the Edsel Ford trophy. The 6,000-mile tour reached 32 cities in 15 states over regions rough enough to test the stability of any plane and the skill of any pilot. In the tiny black and orange monocoupe she named “Miss Memphis,” Phoebe traveled alone, taking neither navigator nor mechanic. She told reporters: “If I take a mechanic, they’ll say that he flew the ship over the bad spots! No. I’ll be my own mechanic, and I’ll fly my plane myself!”

Reporters eagerly followed her progress. They seldom failed to mention that she was one of the few women who made her living flying, and they found her petite size and reputation for fearlessness charming. During the race, she became the first woman to cross the Rockies in a light aircraft.

She ground-looped and flipped the monocoupe in Texas but finished the race with only a few minor injuries and close calls. America staged its first ladies’ race in 1929. It began in Santa Monica, California and ended in Cleveland, Ohio, eight days later. The requirements for entry were a license and a minimum of 100 hours solo experience. Press coverage was flippant. They called it the Powder Puff Derby and the entrants were labeled Petticoat Pilots, Ladybirds, Angels, even Flying Flappers. But the race was by no means all fun. Blanche Noyes was forced to land in a desolate area of Texas when she discovered that the back end of her plane was on fire. She landed, put out the fire and took off again.

At Pecos, Texas, “Pancho” Barnes overshot the runway and hit a car, wrecking both it and her plane. Louise Thaden beat out Amelia Earhart in the DW class, and Phoebe won the light plane division in “Miss Memphis.” She made the 2,723 miles in 25 hours 10 minutes. Then she won a closed course beat-the-clock event at 112.38 mph. That same year, Phoebe was a charter member of the inner sorority of women flyers who founded the Ninety-Nines, an International Organization of Women Pilots initiated by Amelia Earhart to foster sisterhood along with friendly competition.

Phoebe crossed the finish line first in the Dixie Derby of 1930 and took the purse of $2,000. In 1931, after she was the overall winner in the 1931 Transcontinental Handicap Air Derby, besting some 55 other entrants including 36 male pilots, she received a telegram from Eleanor Roosevelt asking her to campaign for her husband. Phoebe took “Miss Memphis” over 20,000 miles to champion Franklin D. Roosevelt across the country.

The Roosevelt camp, in its success, was grateful. After the inauguration, Phoebe received an appropriate appointment: Special Advisor for Air Intelligence to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics [NACA was the predecessor of the National Space and Aeronautics Administration (NASA)]. Phoebe was the first woman in the federal government to hold an official post in connection with aviation. From her desk in Washington, she made more contributions to women in aviation than she could have from the cockpit. Phoebe thought that “if the aviation industry was to grow as large as the automobile industry” then the private pilot, and particularly women, needed to be trained and encouraged.

But she had no illusions about women’s chances of building careers out of aviation. She said, “While I have a transport pilot’s license, I don’t fool myself. The pilots on our airlines are and will continue to be men… I don’t believe there is a future for women flying commercial planes for the same reason that we do not see women at the throttle of express train engines, at the helms of our ocean liners, or driving our big transportation buses.” She didn’t feel it necessary to elaborate what that “same reason” was-that the men wouldn’t let them!

Among her achievements on the NACA was the air marking program she conceived and initiated in 1935. This navigational aid program called for 12-foot black and orange letters to be painted on the roofs of barns, factories, warehouses and water tanks. Visible from 4,000 feet, they identified the locale, gave the north bearing, and indicated by circle, arrow and number the distance and direction of the nearest airport. The air markers were to be placed across the country at 15-square-mile intervals. As part of the Works Progress Administration, air marking provided thousands of jobs for unemployed men.

Phoebe hired female pilots to establish and administer the program in each state. The marker program was an unqualified success. Within a year it was 58 percent completed. Phoebe and her flying staff received well-deserved credit for both an innovative idea and effective execution. The program, however, was short-lived. As World War II loomed on the horizon, panicky civil defense officials feared that the markers might help invading enemy airplanes find their targets. Many were painted over, although a few traces remain visible today. In 1935, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt honored Phoebe Omlie along with a host of women achievers, whom she said had been a constant inspiration to her and to the country and “whose achievements make it safe to say that the world is progressing.”

Unfortunately, personal tragedy soon over-shadowed Phoebe’s triumph. On August 5, 1936, Vernon Omlie and seven others aboard a commercial airliner died when it crashed while trying to land in fog in St. Louis. The plane cartwheeled and blew apart. A devastated Phoebe resigned her post with the NACA and rushed home to Memphis. She did not return to Washington for several years, but she never abandoned aviation. In 1937, Phoebe co-authored the state’s new aviation act, which provided for an aviation fuel tax to be divided between maintenance and improvements to state airports and aviation education for Tennessee’s youth. Phoebe helped establish a system of state supported schools for training civilian pilots that would become a model for the national Civilian Pilot Training Program. Under this program, Phoebe introduced the first vocational courses in aviation in public schools that became part of the curriculum in Memphis city schools.

When it was apparent that the United States would be involved in the war, Phoebe returned to Washington in 1941 as Senior Private Flying Specialist of the Civil Aeronautics Authority, to coordinate aviation activities for the WPA, the National Defense Commission, and the Department of Education. During the first months of that year, she traveled some 12,000 miles and established 66 schools in 46 states.

One of these, in Tuskegee, Alabama, was the only school that trained black pilots. She returned to Tennessee to establish a model program intended to alleviate an anticipated pilot shortage by training women as primary flight instructors for both the Army Air Forces and the Navy. From over 1,000 applicants, Phoebe chose the top 15. The training was tough, and Phoebe expected a lot. She kept it deliberately Spartan and resisted the press’s attempts to talk about her women as glamor girls. The training had to be tough and rigorous, because in such non-traditional arenas, women had to be better schooled, better trained, better skilled and beyond reproach. In all, her school graduated 10 women, who ultimately trained more than 500 men.

When it was inaugurated, the program was expected to train hundreds of women, but the military was reluctant to use them, and when the anticipated shortage of flight instructors did not materialize, the program was disbanded under charges that the women were taking men’s jobs.

After the war, Phoebe worked on research in Washington on flight training methods, including installing photographic and sound recording devices in training planes to record the stresses of students learning to fly.

Phoebe became increasingly unhappy about changes in the Civil Aeronautics Administration as President Truman appointed more non-aviation people to the hierarchy. She abruptly resigned in 1952, complaining about government over-regulation of aviation. She would remain out of aviation for the rest of her life.

Back home, Phoebe bought a cattle farm in Como, Mississippi, something she and Vernon had planned for retirement. Five years later she traded it for a hotel and cafe in Lambert, Mississippi, but that didn’t work out either. She began to withdraw from her friends, started drinking heavily, and moved out of Memphis.

In 1970, Phoebe checked into a fleabag hotel in Indianapolis and never checked out. She lived there for five years, a victim of poverty, lung cancer, alcoholism and old age, too proud to let anyone see her in what she described in letters to friends as her deteriorated condition. She died on July 17, 1975 at age 73. The city of Memphis brought her back for burial next to her husband in Forest Hill Cemetery.

In June 1982, 60 years after Phoebe and Vernon landed in Memphis and brought the city into the air age, a new control tower was erected at Memphis International Airport. It was named in honor of Phoebe and Vernon Omlie.

At the dedication, the focus was on Phoebe’s achievements: “Her place in the pages of aviation history is unchallenged. A woman of daring, courage, intelligence and devotion to the ‘air age,’ she ranks as one of the greatest participants in American progress.”

Have a good weekend, keep family and friends close, and remember that tomorrow your life/my life is one day shorter. Don’t settle for second best.

Robert Novell

November 14, 2014