Lindbergh’s Success and The Forgotten Aviation Pioneer Who Made It All Possible – January 17, 2020

Otto and the Wright Brothers – January 10, 2020

January 10, 2020

Airborne Navigation/Avigation Began With Concrete Arrows – January 24, 2020

January 27, 2020RN3DB

January 17, 2020

Good Morning,

One of the next big events in aviation history is the flight of Lucky Lindy and this week I want to talk about the man who was responsible for many aviation first. His name was B.F. Mahoney and he is responsible for the first scheduled airline to operate on a published schedule, the man behind the “Spirit of St. Louis,” and many other items.

Benjamin Mahoney, who died in 1951 at the age of 50, was often referred to as the mystery man behind the Spirit of St. Louis. He was continuously on the cutting edge as an aviation pioneer and his contributions have never been portrayed in a way that gave him the credit he was due. Take some time to look beyond this article and discover more about the “Mystery Man of Aviation.”

Enjoy…..

The Mystery Man Behind the Spirit of St. Louis

Written by Joseph D. Tekulsky

Left to right: Ryan Aeronautical Company owner B.F. Mahoney, Col. Lindbergh

and aircraft designer/builder David Hall

Charles A. Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis probably is the best known airplane in the world. The airplane’s transatlantic flight brought fame to T. Claude Ryan, whose name is connected to the company that built it–Ryan Airlines, the original Ryan company. But, although the names ‘Ryan and Ryan Airlines appear on the plane, history has overlooked the other name closely intertwined with the legend of Lucky Lindy and his Spirit–Benjamin Franklin Mahoney, owner of Ryan Airlines.

Mahoney was born on February 8, 1901, in Wilkes-Barre, Pa. His success spanned the Jazz Age–he drove a Stutz Bearcat and flew a Thomas-Morse Scout. Well-dressed, affable, energetic, with a quick mind but little prior business experience, he was attracted by the excitement of aviation. Mahoney had confidence in the future of commercial airlines and transoceanic flying, and he was willing to make a commitment to those goals.

Mahoney’s father, the owner of a retail store chain, died while his son was still in school. Mahoney attended Bordentown Military Institute in New Jersey and Mercersburg Academy in Pennsylvania. In 1919, he and his mother moved to San Diego, where he became a bond salesman.

T. Claude Ryan, a former U.S. Air Service pilot, taught Mahoney to fly. In addition to his aviation school at San Diego, Ryan ran sightseeing and charter flights. For these he used World War I Standard J-1 open-cockpit trainers he had modified by replacing the front cockpit with a four-passenger, closed cabin. He also substituted a 150-hp Hispano-Suiza engine for the original Hall-Scott.

Mahoney came up with an idea for an airline. You’ve got the airplanes here doing a lot of local flying, he said to Ryan. Did you ever think about running a schedule to Los Angeles back and forth on a daily schedule basis? Ryan had doubts. Undeterred, Mahoney pointed out that people are more ready to accept flying than you may think. And he offered to put up the money for an airline for a share of the profits.

Ryan agreed, and the Los Angeles San Diego Air Line came into being on March 1, 1925. The fare was $14.50 one way, $22.50 round trip. It was claimed to be the first airline in the United States to operate all year on a regular schedule.

On April 19, 1925, Mahoney bought a half interest in Ryan’s operations–the airline, aviation school and the charter and sightseeing business–for $7,500. The two became partners under the name Ryan Airlines.

In the same year, the partners bought a Cloudster (for Cloud Duster), the first airplane built by Donald Douglas, for $6,000. The huge, open-cockpit, 56-foot-wingspan biplane with a 660-gallon fuel capacity had failed in an attempt to make the first nonstop transcontinental flight in 1921. Ryan and Mahoney converted it for the Los Angeles to San Diego run by building a carpeted and lighted cabin for five passengers, with plush seats on each side of a center aisle. A two-place open cockpit for a pilot and co-pilot was located in front of the cabin.

Ryan Airlines built its first airplane in the fall of 1925. It was named the M-1 (M for monoplane, 1 for first series), and was based on a sketch by Claude Ryan. The fabric-covered M-1 had a tubular-steel fuselage. Its 36-foot wood wing, set above the fuselage and supported by outside braces, resulted in an unobstructed view. Doors on the left side gave access to the open front mail-and-passenger cockpit and to the open rear cockpit for the pilot. The burnished, dappled effect of the metal cowl and covered wheels became a feature of later aircraft. The first M-1, powered by a 150-hp Hispano-Suiza engine, flew in February 1926.

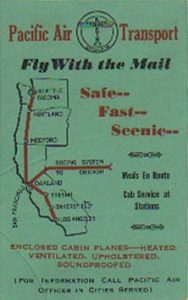

Pacific Air Transport (later absorbed into United Airlines) ordered six M-1s with 200-hp Wright Whirlwind radial engines for airmail service between Los Angeles and Seattle. The partners paid $200 per month to rent part of a vacant fish cannery at the San Diego waterfront for their factory. Twenty-three M-1s were built in the first production year.

The M-1 was followed by the M-2 (a faster version of the M-1 by virtue of a lighter wing) and the Bluebird. The latter was a closed-cabin version of the M-2 that accommodated a pilot and four passengers. Powered by a 200-hp Hispano-Suiza engine, the Bluebird–the only one ever built by Ryan–closely resembled the future Spirit of St. Louis.

The partners discontinued the Los Angeles San Diego Airline in September 1926 after its traffic began to decline. In its 18-month existence, the airline had a perfect safety record.

Unable to agree upon a plan to raise new capital, Ryan and Mahoney terminated their partnership on November 23, 1926. Mahoney bought out Ryan for $25,000 and an M-2. For the time being, Mahoney continued to use the name Ryan Airlines.

Claude Ryan stayed on temporarily as general manager. He later formed Ryan Aeronautical Corp. (now Teledyne Ryan Aeronautical), which built the low-wing, metal, open-cockpit S-T sport trainer. Its military successors were the PT-16, -20, -21 and -22 primary trainers.

Several months after Frank Mahoney became sole owner of Ryan Airlines, in early February 1927, Lindbergh, an airmail pilot familiar with the good record of the M-1 with Pacific Air Transport, wired, Can you construct Whirlwind engine plane capable flying nonstop between New York and Paris…? Planning to compete for the Orteig Prize for the first nonstop flight between the two cities, he had approached several major aircraft manufacturers without success.

Mahoney was away from the factory, but Claude Ryan answered, Can build plane similar M-1 but larger wings…delivery about three months. Lindbergh wired back that due to competition, delivery in less than three months was essential. Many years later, Jon van der Linde, chief mechanic of Ryan Airlines, recalled, But nothing fazed B.F. Mahoney, the young sportsman who had just bought Ryan. Mahoney boldly telegraphed Lindbergh back the same day: Can complete in two months.

Lindbergh arrived in San Diego on February 23. He toured the factory with Mahoney and met factory manager Hawley Bowlus, chief engineer Donald Hall and sales manager A.J. Edwards. After further discussions between Mahoney, Hall and Lindbergh, Mahoney offered to build the plane for $10,580, restating his commitment to deliver it in 60 days.

Lindbergh was convinced: I believe in Hall’s ability; I like Mahoney’s enthusiasm. I have confidence in the character of the workmen I’ve met. He then went to the airfield to familiarize himself with a Ryan plane–either an M-1 or an M-2–then telegraphed his St. Louis backers and recommended the deal, which was quickly approved.

Mahoney lived up to his commitment. Working exclusively on the plane and closely with Lindbergh, the staff completed the Spirit of St. Louis 60 days after Lindbergh arrived in San Diego. Powered by a Wright Whirlwind J-5C 223-hp radial engine, it had a 46-foot wingspan, 10 feet longer than the M-1, to accommodate the heavy load of 425 gallons of fuel. In his 1927 book We, Lindbergh acknowledged the achievement of the builders with a photograph captioned The Men Who Made The Plane, identifying B. Franklin Mahoney, President, Ryan Airlines, Bowlus, Hall and Edwards standing with the aviator in front of the completed plane.

After test flights, Lindbergh flew the new airplane via St. Louis to Curtiss Field, Long Island, arriving on May 12. Mahoney followed by train to join him in final preparations.

Mahoney was with Lindbergh and a few friends in New York City on the evening of May 19 when they learned from the weather bureau that conditions over the Atlantic had suddenly improved. They rushed back to Long Island to watch the next morning as Lindbergh barely cleared the trees on his takeoff.

Mahoney cabled Lindbergh in Paris, Of utmost importance that I join you in Paris…before you sign any contracts…. Lindbergh cabled back, Signing no contracts before reaching America therefore useless come over. But Mahoney and sales manager Edwards favored the trip to publicize Ryan Airlines and the Mahoney name. On May 25, Mahoney sailed on the liner Mauretania and met Lindbergh in Paris. At Lindbergh’s request, the Navy Department granted Mahoney permission to accompany the flier on the cruiser Memphis that was ordered by President Calvin Coolidge to bring Lindbergh and the Spirit of St. Louis back to the United States.

On the evening before boarding Memphis, Lindbergh and Mahoney dined with Ambassador Myron T. Herrick at the U.S. Embassy in Paris. A photograph of Lindbergh’s arrival in Washington, D.C., on June 11, 1927, shows him descending the gangplank followed by his mother, Mahoney and several cabinet members.

Mahoney finally discontinued the name Ryan Airlines in July 1927, incorporating as B.F. Mahoney Aircraft Corporation. Lindbergh’s flight had created great demand for the new AB-1 Brougham developed from the M-2 and the Bluebird. The five-place (including the pilot), closed-cabin plane was equipped with the same 223-hp Wright Whirlwind J-5C engine as the Spirit. It had a 42-foot wingspan, a fuel capacity of 83 gallons and a 750-mile range. The Brougham was advertised as a sister ship of the Spirit of St. Louis with an interior completely upholstered in mohair…roomy, comfortable seats, perfect visibility and…easy access. The initial price of $9,700 was later increased to $12,200.

Racing pilot Frank Hawks flew his B-1, the first production Brougham built, in the Detroit News Air Transport Trophy competition at the National Air Races in September 1927. He finished first in speed and third in efficiency.

On December 31, 1927, Mahoney sold his company, reportedly for $1 million to a group of St. Louis investors, including some of Lindbergh’s original backers. A new company, Mahoney Aircraft Corporation, was formed, with Frank Mahoney named president and a director.

Mahoney Aircraft gave Lindbergh a custom-built Brougham to replace the Spirit he was about to donate to the Smithsonian Institution. Its Whirlwind engine was trimmed with nickel. Other special features included a 46-foot wingspan, a 115-gallon fuel capacity, landing lights in the leading edge of the wing, larger tail surfaces and ailerons, and an electric self-starter. Mahoney flew with Lindbergh on his first flight. Lindbergh’s reaction was: It’s just right. I like it.

The corporation changed its name to Mahoney-Ryan Aircraft Corporation later that year. It closed the San Diego factory where all 150 B-1 Broughams had been built and moved to St. Louis. Eventually, 78 more Broughams would be built there.

Mahoney sold his interest to a member of the St. Louis group in late 1928, ending his association with Mahoney-Ryan Aircraft. Detroit Aircraft Corporation acquired Mahoney-Ryan in June 1929, renaming it Ryan Aircraft Corporation (unconnected with Claude Ryan). Detroit Aircraft ceased business during the depression-ridden 1930s, ending the enterprise originated as Ryan Airlines.

Mahoney suffered financially in the 1929 stock market crash. He later was active in the aviation industry, but he never approached his earlier success. He died of a longtime heart ailment at the age of 50 in 1951.

One of Mahoney’s advertisements for his Ryan Airlines proclaimed the Spirit of St. Louis, The Most Famous Plane in the World. That fame continues, but Mahoney’s does not. However, if he had changed the name of his business to his own a few months earlier, he would probably be remembered today as an important aviation pioneer.

The author wishes to acknowledge the help of the Ryan Aeronautical Library at the San Diego Aero-Space Museum and the Missouri Historical Society in preparing this article.

I hope you enjoyed our look back at what I refer to as, the rest of the story. In addition, I have a photo taken in 1967 at the end of this post that may surprise you. Click on the photo and enjoy a look back at Delta’s history.

Enjoy time with family and friends and hopefully the weekend will allow you to recharge your spirit and prepare you for a new week as a “Gatekeeper of the Third Dimension.”

Robert Novell

January 17, 2020