The Man Who Was Lindbergh’s Equal In Talent And Accomplishments – January 21, 2017

Imperial Airways and Pan Am – Their Business Plans Were Very Similar – January 13, 2017

January 13, 2017Nunc a pretium velit

February 3, 2017Robert Novells’ Third Dimension Blog

January 20, 2017

Good Morning,

I hope the week was good for you and you will have some time off over the weekend to relax and unwind. This week we are going to revisit aviation in South America and specifically Argentina. Argentina considers Jean Mermoz the “Father of Argentine Aviation,” as well as a national hero, and this is the focus of the blog today.

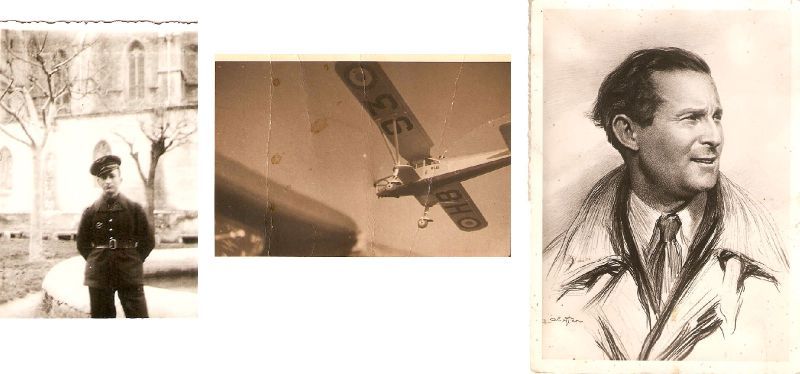

Jean Mermoz, who was born in France in 1901, is a national hero in France as well as being nicknamed “France’s Lindbergh” by the press. I wrote an extensive article on the life of “France’s Lindbergh,” and to view that article please click here Jean Mermoz; however, for today I want you to view an article from the Smithsonian titled “10 Great Pilots.” I hope that you enjoy the brief details presented and you will possibly have time, later in the weekend, to do some research on your own so that you, as Paul Harvey would say, will know the rest of the story.

Enjoy………………………….

Jean Mermoz

In January 1921, on his third try, Jean Mermoz got his pilot’s license. Three years later, he signed up as a pilot with Lignes Aeriennes Latécoère, and set out to attain the goal of aircraft designer for Pierre Latécoère: to create an airmail line linking Europe with Africa and South America.

In 1926, Mermoz had engine trouble over the Mauritanian desert and made an emergency landing. He was captured by nomadic Moors and held prisoner until a ransom was paid—a common practice and one of the many torments on the Latécoère airmail routes, which linked Toulouse to Barcelona, Casablanca, and Dakar. Mermoz was lucky—five Latécoère pilots were killed by Moors. Other hazards: the hostile Sahara, impenetrable Andes, and 150-mph winds that roiled over the southern Argentine coast.

In 1927, Lignes Aeriennes Latécoère became Compagnie Général Aéropostale, and Mermoz took charge of the South American routes. He made Aéropostale’s first South American night flight in April 1928 from Natal in Brazil to Buenos Aires in Argentina, along a route unmarked by any sort of beacon. After he showed the way, mail delivery was no longer restricted to daylight-only operations.

Mermoz next tackled shortening the Argentina-to-Chile route; pilots had to make a thousand-mile detour to get around the Andes. With mechanic Alexandre Collenot, Mermoz set out in a Latécoère 25 monoplane and found an updraft that carried them through a mountain pass, but a downdraft smashed the aircraft onto a plateau at 12,000 feet. After determining that they could not hike out, Mermoz cleared a crude path to the edge of the precipice and removed from the aircraft anything that wasn’t bolted down. He and Collenot strapped themselves in, and Mermoz got the airplane rolling down the path. In effect, they dove off the mountain, and Mermoz pointed the nose straight down, hoping to gain flying speed. Again, luck was with him. And in July 1929, with the acquisition of Potez 25 open-cockpit biplanes that had a much higher ceiling than the Laté 25, Mermoz and Henry Guillaumet opened a scheduled route between Buenos Aires and Santiago.

In early 1930, Aéropostale looked to bridge the Atlantic. Mermoz, in a new Latécoère 28 float-equipped monoplane, took off on May 12 from St. Louis, Senegal, with a navigator, a radio operator, and a load of mail. As night fell, they flew into a series of waterspouts that rose into stormy clouds. In Wind, Sand and Stars, published in 1940, fellow Aéropostale pilot Antoine de Saint-Exupéry wrote: “Through these uninhabited ruins Mermoz made his way, gliding slantwise from one channel of light to the next, flying for four hours through these corridors of moonlight. And this spectacle was so overwhelming that only after he had got through the Black Hole did Mermoz awaken to the fact that he had not been afraid….”

Mermoz flew 1,900 miles in 19.5 hours, and landed in the Natal harbor the next morning. “Pioneering thus, Mermoz had cleared the desert, the mountains, the night, and the sea,” Saint-Exupéry wrote. “He had been forced down more than once…. And each time that he got safely home, it was but to start out again.”

The U.S. press called Mermoz “France’s Lindbergh.” On December 7, 1936, Mermoz departed Africa in a four engine seaplane, bound for Brazil, on the weekly mail run. It was his 28th Atlantic crossing. Neither he nor his crew was seen again.

Have a good weekend and thanks for letting me be a part of your day. Fly safe, be safe, and join me next week when we continue our look back at the pioneers of aviation.

Robert Novell

January 20, 2017