The Quest For Speed – September 05, 2014

NTSB Faults Gulfstream for Crash – September 1, 2014

September 1, 2014

Aviation Wisdom From the Past – September 9, 2014

September 8, 2014Robert Novells’ Third Dimension Blog

September 05, 2014

Good Morning and Happy Friday,

Last year I posted two articles on the SST program and recently I was having a conversation with a friend who was totally unaware that it was President Kennedy who brought the SST program alive in the 60s so this week I want to revisit that subject. This weeks blog will have both posts dealing with the SST so sit back, relax, and enjoy the story on “The Quest For Speed.”

President Kennedy’s Quest for Speed

The Kennedy years were troubled years, sprinkled with some major accomplishments, and President Kennedy’s commitment to put a man on the moon would prove to be the crowning jewel; however, how many of us know, remember, that it was also President Kennedy who started the race to build the Super Sonic Transport?

The Kennedy years were troubled years, sprinkled with some major accomplishments, and President Kennedy’s commitment to put a man on the moon would prove to be the crowning jewel; however, how many of us know, remember, that it was also President Kennedy who started the race to build the Super Sonic Transport?

On June 5, 1963, during a speech being given at the Air Force Academy, President Kennedy announced that the government would team up with private industry to build the world’s fastest commercial airliner that would be superior to any other country. Of course what the President was saying was that the U.S. would produce a superior machine to what the Anglo-French project called the Concorde. The president later remarked off camera that “We’ll beat that bastard De Gaulle.”

So began the race for speed……………

The Kennedy administration was confronted with many difficult situations but amid the turmoil Kennedy established several milestones that would propel the U.S. forward, technologically, in an effort to maintain our position as number one. We are all familiar with the Apollo program but Kennedy was also responsible for the SST program.

The pressure was on the administration to respond to the Anglo-French Concorde, as well as the Soviet’s TU-144, in order to protect America’s leadership position in aerospace as well as the balance of payments in the international arena. Pan Am had already announced that they were taking options on six Concordes as well as BOAC and Air France had announced they would be signing options as well.

The administration’s response was to propose a bigger, and faster, version of the SST. Kennedy had already been briefed by a multi-agency committee, headed up by Vice President Johnson, that a larger, and faster, version of the SST was feasible. The proposal revealed that an airplane capable of 2000 MPH, three times the speed of jet liners introduced only a few years earlier, carrying 300 passengers was attainable; however, Kennedy proposed to Congress that this could be done for one billion dollars which would prove to be way off the mark.

Although the U.S. was getting in to the race behind the Concorde, and the Soviets, the airplane Kennedy envisioned would be faster and more efficient than that which had been proposed, and administration officials pointed out that the Europeans, in their haste to be first, had sacrificed the potential to grow in speed and size. Finally, after months of review by the FAA four companies were asked to submit final proposals. GE and Pratt and Whitney were to compete for the engine to power America’s SST and Boeing and Lockheed would compete to be the manufacturer of the airframe.

Boeing came forward with the boldest design of all. Their concept used variable-geometry wings which was unprecedented for civil aviation. Boeing had perfected the swing wing design when they were competing for the multiservice fighter contract that was awarded to General Dynamics and their F-111 concept. In addition to the swing wing GE was proposing an updated version of the YJ-93 engine that they were using on the XB-70 (see photo below). GE designated the new engine the GE4 and their engine would develop supersonic speed by being the world’s largest afterburner. While Boeing was the ultimate winner in the competition, along with GE, there were many difficult problems to overcome. However, the one problem they could not fix was the mindset of Congress.

Lockheed would put forth a design modeled after a secret reconnaissance aircraft that would later become famous as the SR-71 Blackbird. Lockheed’s design would be faster at Mach 3, as opposed to Mach 2.7 proposed by Boeing, and would also carry 300 passengers; however, their design was rejected because of the “Delta Wing.” What is ironic about this rejection is that Boeing was forced to abandon the “Variable-Geometry Wing,” because of weight, and adopted the “Delta Wing” in its final design much to the surprise of Lockheed and others.

The showdown on continuing the construction of the two prototypes by Boeing came in 1971 when Congress was asked for another eighty-three million dollars to continue the program. All of the supporters of the program argued it would be foolish to cancel the program considering the one billion dollars already invested but Washington was not listening. The program was canceled.

Much of the blame for the cancellation was given to the environmental groups who had lobbied hard for their cause. These groups had taken out ads declaring the SST would shatter windows in homes, stampede cattle and other range animals, and would hasten the end of the “American Wilderness.” However, in the final analysis Washington concluded that the project just didn’t make sense. With air travel in a slump, and fuel prices soaring, even Boeing, GE, and most airlines had doubts about the success of the airplane.

Considering the lack of success by the Concorde the decision by Congress seems to have been the right one.

Cancelling the SST program idled over 13,000 aerospace workers and years later Boeing’s CEO admitted that they came very close to declaring bankruptcy; however, they did survive, as did GE who had to idle more than 1600 employees, and both companies maintained their leadership role in the industry.

That is it for this week. I hope everyone has a good weekend and will enjoy some free time away from work. Please join me next week when I will talk about commercial aviation after the SST.

**********

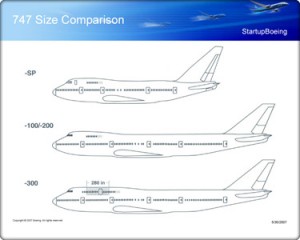

Lockheed went on to build the C-5 Galaxy, which was a money loser for them, and Boeing brought the 747 to life. So, let’s talk about Boeing and one of my favorite airplanes.

Boeing Rebounds From The SST Debacle

“Oh my gosh. How are we going to get an engine big enough to carry that weight?” That was Joe Sutter’s, father of the Boeing 747, reaction when tasked with the challenge of building an airplane 2.5 times bigger than the 707 that could hold 350 to 400 passengers. It was the 1960s, and commercial aviation was growing. Sutter led “The Incredibles,” a group of 50,000 Boeing construction workers, mechanics, engineers, secretaries and administrators, which brought the behemoth to life.

The gigantic, efficient and ubiquitous Boeing 747 transport is a symbol of the most important aspects of progress in civil aviation: the democratization and globalization of travel. At this instant, thousands of airline terminals around the world are crowded with millions of people representing every nation, all taking advantage of the availability of long-distance travel via flight.

Although modern, the Boeing 747 also symbolizes another era, when individuals like Juan Trippe of Pan American Airways and Bill Allen of Boeing could decide to undertake a venture of giant size. and great risk, and do so on their own, certain that their decisions would be approved by their boards of directors.

It was on December 22, 1965, that Trippe and Allen signed a letter of intent committing $525 million, for 25 aircraft, launching the largest airliner in history – the Boeing Model 747. The initial specifications called for a gross weight of 550,000 pounds, room for up to 400 passengers, a cruise speed of Mach .9, and a range of 5,100 miles.

It was a fantastic challenge, one whose failure had the potential to ruin both companies. New engines had to be designed and built as did a huge new factory that would house the largest building in the world in terms of volume. Even the world’s airport runways, taxiways, and terminals had to be redesigned to handle the aircraft.

Jack Waddell was pilot on the first 747 flight, on February 9, 1969, and as all test pilots must do, he publicly called the giant new airplane “a pilot’s dream.” There would be delays in getting the 747 into service, primarily due to problems with the Pratt & Whitney JT9D engines, but it was soon apparent that the Boeing 747 was the new world standard in transportation.

Fast, comfortable, and reliable, Boeing 747s began racking up one record after another. By 1975, it had carried its 100 millionth passenger, signifying the beginning of the revolution in air transport. That revolution was confirmed by the year 2000, when 3.3 billion passengers had been carried, and 747s had flown over 33 billion statute miles.

Now we all know that the 747 was a success, and began the widebody revolution, but let’s talk about how Boeing managed to lose a contract that made them the winner in this new era.

The old saying “Be careful what you ask for – you may get it” holds true in the highly competitive world of aviation. In 1964 Boeing, Lockheed, and Douglas were players in an intense competition to win a contract for a very large military transport. It became apparent early on that Douglas was not going to win, the Boeing entry was favored by the Air Force, but the Lockheed bid was $250 million lower in price.

Lockheed was delighted when it was awarded the contract to build the C-5A, and Boeing was furious. However, the C-5A contract was a brand-new contractual instrument termed Total Package Procurement. It was an unfair arrangement that was essentially a firm fixed-price development program. The terms of the contract were harsh enough to cause Lockheed to lose hundreds of millions of dollars. Boeing, on the other hand, used the development experience to design the 747, and went on to make billions of dollars in the process.

Now you know the rest of the story…………………………………

Have a good weekend, enjoy the videos below, and remember that all aviators are “Gatekeepers,” and we all must protect the interest of those who will follow in our footsteps.

Robert Novell

September, 04, 2014