Rumrunners, Pappy Chalk, and a Miami Airline – February 23, 2024

The Hercules…..The Four Horseman…..Fat Albert – February 16, 2024

February 16, 2024

The Day The Japanese Bombed Oregon – March 1, 2024

March 1, 2024RN3DB

February 23, 2024

Good Morning,

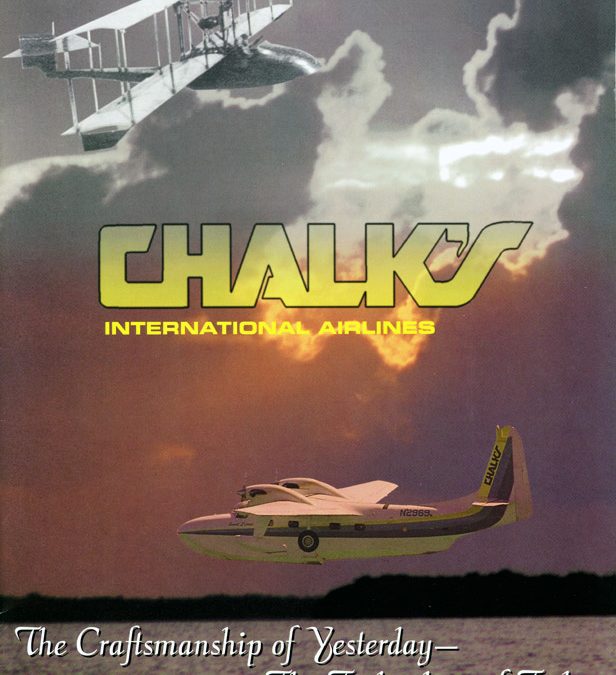

Today I want to talk about a company called Chalks and how a man named Arthur Burns Chalk became a seaplane pilot and owner of an airline.

Arthur Burns Chalk, who I will call Pappy Chalk from this point forward, was working as a mechanic in Paducah, Kentucky in 1911 when a chance encounter with a man named Tony Janus would change his life forever. Tony Janus had made a landing on the Ohio River, after developing engine trouble, outside town and was in need of repairs. Pappy Chalks agreed to fix the engine if Mr. Janus would teach him to fly and a deal was struck. I have talked about Tony Janus before, CLICK HERE, in a previous blog but to refresh your memory Mr. Janus started the first scheduled airline service in America operating from Tampa to St. Petersburg, Florida and his bio can be found here…TONY JANUS.

In 1917 Pappy Chalk went south and initially he made his living as a barnstormer, but in 1917 he founded the Red Arrow Flying Service on the dock of the Royal Palm Hotel in Miami. His office was a small table under a beach umbrella, and his reservation system was a single crank telephone hanging from a pole. Because neither Miami nor the Bahamian islands had airports Pappy Chalk equipped his three-seat Stinson Voyager with floats so that he could take off and land the aircraft on water.

In 1919, the operation, by then named Chalk’s Flying Service, inaugurated a regular schedule to Bimini, a Bahamian island 50 miles off the southern Florida coast; however, remember that in the US the prohibition era was in full swing and rum runners, and their pursuing lawmen, formed much of Chalk’s clientele. Wealthy big game hunters and fisherman, typified by Ernest Hemingway, also became regular customers after the repeal of prohibition in 1933.

Pappy Chalk, and his airline, had many accomplishments to his credit including rescuing deposed Cuban President Gerardo Machado amid of volley of bullets and operating submarine patrols during World War II; however, my space is limited here but I encourage you to do some research on your own.

Pappy Chalk retired in 1964 after the death of his wife, Lillie Mae Chalk, who had helped run the operation since their marriage in 1932. Dean Franklin, Chalk’s long-time friend, bought the airline in 1966, adding service to Key West and Fort Jefferson the following year.

Now I have a brief profile of Chalk’s history in the 70s, 80s, and 90s from an article on the web:

Chalks in the 70s/80s

In the late 1970s, Chalk’s began using 30-passenger G-111 Albatross seaplanes, a modification of the venerable HU-16, which had been produced as a military aircraft between 1949 and the mid-1960s. At the time, Chalk’s was flying about 45,000 passengers a year, and demand was increasing. No aircraft companies were then making commercial amphibious airplanes, so Chalk’s upgraded its own. Antilles Air Boats was acquired in 1979. Service between Miami, Paradise Island, and West Palm Beach began in 1981. The company upgraded the fleet of five 13-place Grumman G-73 Mallard aircraft to turboprop engines in the early 1980s, at a cost of $4 million. The TV show Miami Vice, a symbol of both Miami and the 1980s, featured a Chalk’s seaplane in its opening credits.

Chalk’s fleet was as high-maintenance as it was glamorous. It was a unique carrier, its Watson Island base being the smallest port of entry in the United States. Chalk’s revenues were about $7.5 million in 1986, when it carried 130,000 passengers. Most were staying at Resorts International properties, although island residents used the airline for shopping trips to Miami. Resorts International owner Jim Crosby was an enthusiastic supporter of the airline and began to expand its fleet with 13 thoroughly upgraded, 30-passenger Grumman G-111 seaplanes. After Crosby’s death, these planes went into storage in Arizona.

Donald Trump acquired Resorts International in 1987. He owned it for a year before selling it to Merv Griffin Enterprises. Chalk’s signature seaplanes were restricted to daylight operations due to the difficulty of ascertaining landing conditions on water at night. In March 1989, Resorts launched another airline, Paradise Island Airways, to handle increased vacation traffic from Florida to the Bahamas. Its three 50-seat, STOL (short take-off and landing) Dash-7 planes were operated by Chalk’s personnel to land-based airstrips. The two brands were carrying more than 60,000 passengers a year, only a quarter of them on Chalk’s seaplanes. A handful of other small South Florida airlines, like Aero Coach, plied the skies between Miami or Fort Lauderdale and Nassau or Freeport.

Crossing Stormy Seas in the 1990s

The 1990s began with the near-closing of the airline and its sale in early 1991 to United Capital Corporation of Rockford, Illinois. This venture capital group was owned by Seth and Connie Atwood, two seaplane enthusiasts. The legal entity was called Flying Boat, Inc., but the airline continued to do business under the Chalks name. Chalk’s passed an interesting milestone on June 28, 1991, when it flew its first scheduled domestic flight, connecting Miami directly to the Florida Keys. The company had nearly 30,000 passengers in 1991.

Chalks became licensed to perform maintenance for other seaplane operators in 1993. After 75 years of flying, Chalk’s experienced its first fatal accident in March 1994 when one of its seaplanes crashed upon take-off from the Florida Keys. Two crewmembers were killed. A group of investors then acquired Chalk’s–known as Chalk’s International Airlines at the time–for about $5 million in January 1996. The partners included Miami developer Craig Robins; Chuck Slagle, owner of Alaska’s Seaborne Aviation; and Chuck Cobb, who held rights to the Pan Am name.

Chalk’s began operating as Pan Am Air Bridge on March 1, 1996. However, the airline was not a feeder airline for the new Pan Am, which had returned to operations along the East Coast. The legendary trademark evoked the massive Clipper flying boats that the original Pan American had flown to exotic destinations. Pan Am Air Bridge was then operating a fleet of five Grumman seaplanes. The former Chalk’s was up for sale again by September 1997. By this time, it was breaking even. Aircraft leasing company Air Alaska acquired a 70 percent share in the company from Craig Robins in January 1998 for $2 million, at the same time signing notes for another $8 million for five of the company’s planes. Pan Am Corp., through its Pan American World Airways unit, retained a 30 percent holding in Pan Am Air Bridge. Air Alaska also acquired land rights to its Watson Island base. A few months later, Guilford Transportation Industries acquired a 30 percent holding in Pan Am Air Bridge via its purchase of Pan American World Airways.

An involuntary bankruptcy temporarily grounded Pan Am Air Bridge in February 1999. It soon restarted operations under its former name, Chalk’s International Airlines. Chalk’s was rebranded again in December 1999, as Chalk’s Ocean Airways. That month, the company relaunched service, opening a new route to Paradise Island, in the Bahamas, whose airport had been closed and was directly accessible only by seaplane. Chalk’s planes were refurbished and repainted for the opening; the company’s terminals were also being upgraded. Paradise Island Airways, Chalk’s land-based air service, closed in May 1999. Miami entrepreneur and former Eastern Airlines pilot Jim Confalone acquired Chalk’s out of bankruptcy on August 2, 1999, for $925,000. By this time, it was operating just two leased aircraft and had only 35 employees. After buying the airline, Confalone agreed to buy 14 30-seat Grumman G-111 seaplanes from Chalk’s former owner, Seth Atwood of Chicago.

Hope on the Horizon in 2000 and Beyond

The tremendous growth of the Bahamas as a tourist destination, particularly among the affluent, boded well for Chalk’s niche, a blend of transportation, convenience, and entertainment. In 2000, Chalk’s began flying from Fort Lauderdale to a Freeport resort, called “Our Lucaya,” which was being overhauled by Hong Kong developer Hutchinson & Whampoa Ltd. Like most airlines, Chalk’s was affected by the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks on the United States. It cut schedules by up to 25 percent, and reduced its operations from four full-time aircraft to three flying part-time. The schedule was soon restored, however. While major carriers such as United and American Airlines were dealing with bankruptcy issues, Chalk’s was beginning to grow again, though the 2003 war in Iraq prompted another temporary slowdown. Confalone described his “CEO” business model to the Miami Herald: “Customer is first, the Employee is second, and the Owner is last.” To ensure the promptest service, employees were discouraged from talking to each other on duty, a practice Confalone borrowed from The Car Wash, one of his successful service-driven enterprises. In 2003, some industry analysts speculated that Chalk’s might return to profitability in the coming year. With its long history of weathering financial turbulence, Flying Boat and Chalk’s seemed likely to remain a leader in its niche market.

In 2005 a Chalk’s Turbine Mallard snapped a wing leaving Miami killing all eighteen on board. The NTSB report is on the web for those of you who are interested, but this accident marked the beginning of the end for Chalks. The FAA revoked their certificate in September of 2007 and the airline ceased operations before year’s end.

Chalks International Airline was a good company, with good people, and a loyal clientele that made them a unique entity in the history of US aviation.

That’s it for this week, enjoy the photos/video below, enjoy your weekend with family and friends, and from all of us at the 3DB we wish you, and yours, the best that life has to offer in the coming weeks, months, and years.

Robert Novell

February 23, 2024