Transocean Airways – A look Back (Part Two)

Aviation Wisdom From the Past

May 29, 2014The Age of The iPad

June 3, 2014“Robert Novell’s Third Dimension Blog”

Good Morning and Happy Friday—Today we will finish up our look-back at Transocean Airlines and it is my hope that you have enjoyed this history lesson on a company who’s expertise reached all corners of the globe.

TRANSOCEAN AIRLINES

Part Five

Around the World with Transocean Air Lines

Pakistan

In November 1947, Nelson headed for India and Pakistan looking for business. While in Calcutta he met with executives of Orient Airways to sell them three twin-engine C-47s and two twin-engine Beechcraft. Through these contacts Nelson and TAL became involved in the founding of Pak-Air, Ltd. This new airline was to serve Pakistan which had recently become self-governing, yet still within the British Commonwealth.

After many months of negotiations between Pak-Air and Transocean’s Bill Rivers, a contract was forged to establish air service for Pakistan with the Haroon family, one of the ten wealthiest families in the world at the time. The agreement called for Transocean to provide Pak-Air with flight crews, operations and maintenance staffs for Pak-Air routes from Karachi to London and Singapore, and to assist in the establishment of domestic routes. TAL’s Sam Wilson was sent to Karachi to assist the young airline in its operations. Later, when the Haroons decided they needed experienced management, Transocean was given the contract to run the airline.

But a crisis was already brewing when Flight Captain Dan McCarthy arrived in Pakistan in the spring of 1949 to relieve Sam Wilson from his TAL duties. Sam had been Transocean’s first-in-command of their operations in Pakistan. The crisis began when many of the Pak-Air copilots felt they had served their apprenticeship and wanted to be checked out as captains. Some of these copilots had trained at the Taloa Academy of Aeronautics (a subsidiary of TAL at Oakland International), and some had flown in the Royal Indian Air Force. Still others had gained their experience flying domestic routes throughout India and Pakistan. Captain McCarthy was distressed to find that most of the men who had not been previously trained at Transocean’s academy were unqualified as copilots and immediately fired five of them as he feared they might cause an accident. The firing brought a swift and angry reaction from Pakistani pilots who promptly complained about their termination to relatives who were among the principal investors.

The administration of the airline had been delegated by the Haroon family to Hussain Malik, a Pakistani lawyer and a graduate of Cambridge University in London. Malik conceded that McCarthy was right in principle, but he was under substantial pressure from the Pakistani investors. Finally, he directed McCarthy to put the pilots back on flying status with the airline. Captain McCarthy immediately canceled Transocean’s management contract. An orderly transfer of management was accomplished over the next thirty days. This was with the understanding that TAL would no longer assume responsibility for the operation.

Ten days following TAL’s pullout, a Pak-Air DC-3 with a full load of passengers crashed on a mountaintop during a flight from Calcutta to Karachi, killing all on board. At the controls were two of the pilots McCarthy had fired. They had apparently miscalculated the force of the wind and descended too soon on an estimated time of arrival (ETA) over Karachi.

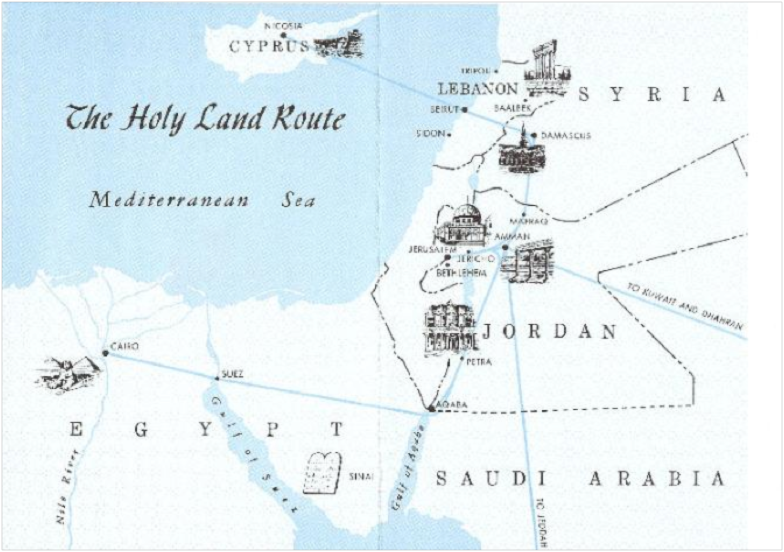

Afghanistan

Afghanistan was the next country to enlist the services of Transocean. The year was 1953. This mountainous country with a primitive transportation system relied heavily on small trucks and camel caravans to move goods over the Khyber Pass to and from distant markets. The government contracted for weekly TAL air service between Kabul and Cairo with intermediate stops at Kandahar and Jerusalem. Connections to Western Europe and the United States were made at Cairo, Egypt.

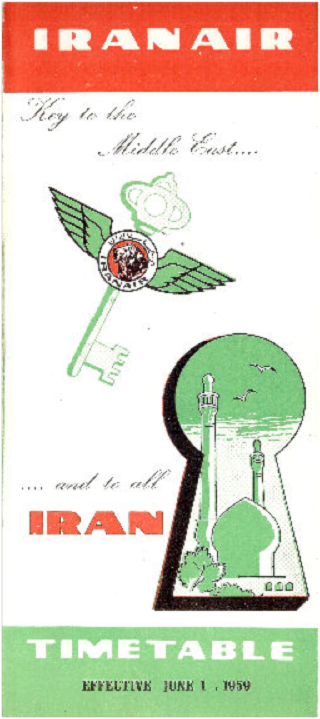

Iran

Iran was yet another country to benefit from Transocean’s assistance. TAL first began operations there in 1948 by training Iranian Air Lines pilots and providing aircraft maintenance. In addition to flying the Moslem pilgrims to Jeddah, they often flew the Shahanshah of Iran, His Imperial Majesty Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi, on journeys to Rome, Geneva, Rabat, Formosa, Japan, or other destinations. The first flight by the polar route from Oakland International Airport was made to deliver a TAL DC-4 to Iranian Air Lines in Teheran. The aircraft departed on January 7, 1955, with Orvis Nelson in command with a crew of six. On board were 8,000 pounds of cargo that included spare engines and arctic survival gear. The first stop was at Duluth, Minnesota, for final clearances and special winterizing of the plane. There, de-icing gear and special fluids to resist the cold would be installed. The polar route chosen by Nelson was similar to the one flown by Scandinavian Airlines Systems (SAS). It penetrated 200 miles north of the Arctic Circle. The course took them within twenty miles of Bluie West 8, code name of a U.S. military air base in Greenland. Their next stop was Keflavik, Iceland. Then they proceeded to Beirut via Dusseldorf, Geneva, and Athens.

TRANSOCEAN AIR LINES

Part Six

Around the World with Transocean Air Lines

Air Djibouti & Air Jordan

The year was 1949. The governor of French Somaliland was envious of Ethiopian Air Lines and the British Aden Airways flying in and out of Djibouti with big cargo loads. But French Somaliland had no money, and France gave little encouragement for the country’s future. The governor asked John Russell, a Trans World Airlines (TWA) employee then serving as operations manager for Ethiopian Air Lines, if he would form a national airline using the name Air Djibouti. “We would be the carrier for the country, and this would provide us the necessary reciprocal landing rights in foreign countries,” said Russell. “The possibilities of using C-46s for cargo were apparent to lower the ton/mile cost.”

“Bill Pearce, who was with Ethiopian in Addis Ababa, and I decided to look for financing for Air Djibouti. We found a listener in Orvis Nelson of Transocean Air Lines. “One of the reasons Nelson was willing to proceed was that our government was offering new C-46s, including spares, for $300 a month with the latest Pratt & Whitney engines and three bladed props, not the troublesome Curtiss Electra props previously used.”We started with two aircraft (one had 3.4 hours flying time, the other 4.5 hours) and modified them at Transocean’s base at Bradley Field, Connecticut. “Bill Glenn and I took the second plane over in midwinter. We had an engine change at Goose Bay, Labrador, with two feet of snow on the ground. Glenn, with the help of the military, did the job in less than two days in sub-freezing temperatures, which was an outstanding feat.

“Our next stop was at Thule Air Force Base in Greenland, and then continued to Shannon, Ireland, and on to Rome, where we picked up my wife and ten-month-old daughter and flew to Asmara, Eritrea, on the Persian Gulf. This was to be our home base as it was under the control of the United Nations and because there was no housing available at Djibouti. “Verne Shrewsbury, who had preceded us with the first C-46, had everything organized on our arrival.”From its headquarters in Asmara, Air Djibouti DC-3s ferried fresh meat and vegetables from the plentiful East African plateau country to the desert outposts of Saudi Arabia, its capital city Riyadh, and to the Arabian-American Oil Company (ARAMCO) installations around Dhahran. Air Djibouti airplanes also transported cargo and conducted (in conjunction with Nairobi Air Services of Nairobi, East Africa) big game camera or shooting safaris from Saudi Arabia to the Nairobi area. Brochures advertising the tour service stated that Air Djibouti could fly passengers to “the exciting land of safaris, trout fishing, sailing, surf bathing, underwater fishing, and glamorous evenings in just twelve hours-ten times faster than the old Magic Carpet record.” The operation also flew religious pilgrims from Kabul, Afghanistan, to Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. From Jeddah they would continue to Mecca on foot because non-Moslems were not allowed in the holy city.

The crews had to carry five-gallon or thirty-gallon drums of gasoline to have fuel for the return leg to Asmara after delivering the hajjis home, which was quite a logistic problem. “In the middle of this operation I received a cable stating that the government of French Somaliland had been overthrown and that the governor had been assassinated. It closed with the command: DO NOT LAND IN DJIBOUTI. “Three countries – Egypt, Lebanon, and Jordan – were considered as possible bases from which to operate our charter business since we were no longer able to land in Djibouti. In December 1951 Libya attained its independence as a constitutional monarchy after years of rule by Italy and after the end of World War II by a British mandate. This North African desert country with a coastline on the Mediterranean Sea is inhabited mainly by wandering Bedouin tribesmen. In the extreme south live the veiled Tauregs. Air Jordan was called upon by Libya for assistance in its race to develop its oil fields. Its services were used by Mobil oil of Canada, Continental Oil Company, Caltex, Standard Oil of Indiana, and Robert Ray Geophysics, Inc., in addition to ARAMCO. Scheduled flights by Air Jordan provided supplies and services to the desert oil camps. In addition to the cargo, Air Jordan carried oil crews who were given one-week furloughs in Tripoli or Benghazi at the end of every four weeks of work in the desert.

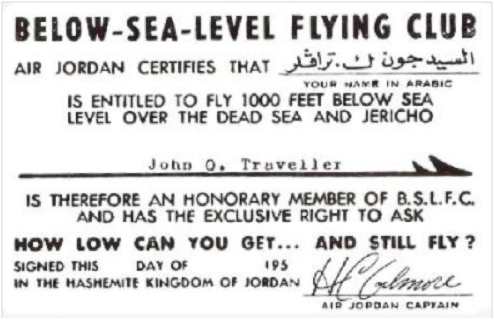

Publicity for Transocean Air Lines often took creative turns as well. For example, Transocean’s Dave Gregory capitalized on the fact that the air route from Cairo to Jerusalem passed over the Dead Sea at 1000 feet below sea level. Dave founded the “Below Sea Level Flying Club.” Several hundred bright yellow membership cards were printed with the Air Jordan logo which certified that the card holder was a qualified member of the exclusive club and had the right to ask: “How low can you get …and still fly?” The club’s cards were the topic of conversation among flight crews and seasoned travelers of other airlines transiting the Middle East. Surprisingly, this club generated considerable business for Air Jordan.

TRANSOCEAN AIR LINES

Part Seven

Around the World with Transocean Air Lines

Japan

By 1950, Transocean was prominent in the Orient, and Nelson finally had his chance to set up the first operation of a scheduled Japanese airline during October of 1951. TAL’s operation was established under an agreement with Northwest Airlines, which had been awarded the original contract by the Japanese. But at the time, Northwest was unable to furnish the equipment and crews, and Transocean had both. Therefore, TAL was given a subcontract and started the service with four Martin 202s and in February of 1952, flew out two more Northwest airplanes to supplement the operation. The flights linked the main island of Honshu with the industrial centers on the other islands and the Martins carried about 80 percent load capacity. On October 23, 1952, the corporation entered into a contract with Japan Air Lines whereby TAL would furnish all flight crew personnel and dispatchers, plus seven instructors, under the direction of Gene Cohan, Director of Far East Operations for Transocean, to train crews for the JAL domestic routes. Among the station managers at JAL were Dick Laskelle and Larry Bovat, with Dispatcher Vic Lakin. The contract also called for a maintenance facility, Japan Air Lines Maintenance Company (JAMCO) to be established, with mechanics and instructors to be supplied by Transocean. Within the year, TAL also furnished flight crews for JAL’s international operation, with a minimum of twenty-four additional TAL flight crew members assigned to the operation.

On September 15, 1953, Captain Claude Turner, Japan Air Lines’ chief pilot, delivered the first DC-6B to Japan to inaugurate JAL’s international service on November 1, which would provide two flights a week between Tokyo and San Francisco.

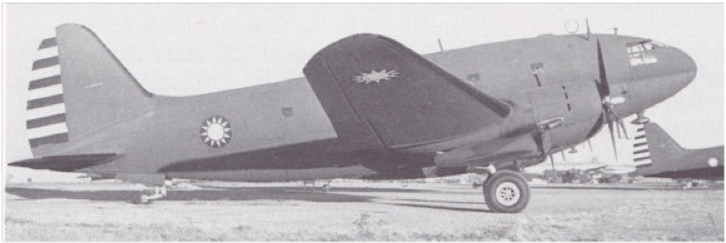

China

The largest, most daring, ferry operation ever undertaken by a civilian airline was accomplished by Transocean flight crews and maintenance men during the spring of 1948. It began when the Chinese Nationalist Air Force purchased 150 Curtis C-46 twin-engine aircraft from the U.S. government and asked Transocean to bid on the “de-mothballing” of the stored surplus aircraft, the overhauling of the planes and the engines, and their delivery to Shanghai, China. They were to be used by General Chiang Kai-shek’s air force. Transocean lost the contract for the overhauling of the engines but presented such a daring and ingenious plan for the transfer of the airplanes to Shanghai that Nelson and his associates won the ferrying contract.

Transocean’s idea for solving the transportation problem was to fit the C-46 Commandos with auxiliary long-range fuel tanks and fly them across the Pacific to China. All the other bidders had insisted on dismantling the overhauled aircraft and shipping them across the Pacific by steamship. Heavy odds were placed against the success of TAL’s projected sky ferry operation. Experts estimated a loss of at least 7 aircraft, so Transocean acquired 157 to fill the contract. But this was exactly the sort of challenge that Nelson and his staff enjoyed.

The special cabin tanks to extend the range from 1,500 to 2,600 miles were installed in each C-46 at Transocean’s Oakland maintenance base. Then test flights were made to determine the fuel consumption of the modified transports. Detailed arrangements were then made to station mechanics at the Pacific island bases on the route. At these intermediate points would be spare parts, engines, and fuel. The flight plan called for a zigzag route originating in Los Angeles, then to Oakland, and on to Honolulu, Wake (or Midway), Guam, Okinawa, and finally to Shanghai. The C-46s were dispatched in groups of 5, and a Transocean DC-4 was later flown to China to bring the crews back to Oakland.

On April 20, 1948, Captain Frank Kennedy, flew the first C-46 (C46320) into Shanghai, but not without incident. The long-range fuel tanks (formerly cabin tanks in DC4s picked up from military surplus) installed in the C-46 cabins, consisted of a metal shell with a neoprene rubber bladder inside. The metal container was not leak-proof, the bladder was supposed to be – or rather, would have been – had it been allowed to maintain its form (more on that later!). These auxiliary fuel tanks were connected to the aircraft fuel system with turn-on valves – some of them common water faucets. A vent from the bladder to the exterior of the aircraft was installed in order to allow air to flow into the bladder as fuel was used by the aircraft. This was to maintain the shape of the neoprene and prevent collapse. The vent was cut off at a 45 degree angle as many exterior vents are.

Captain Kennedy reported, “After a 12½ hour flight from the mainland to Honolulu Airport, gasoline was found to be running out the rear door of the aircraft. The combination of fuel consumption and the 45 degree angle on the bladder vent put negative pressure on the bladder, allowing it to collapse within the metal shell. This caused cracks within the wall of the neoprene to leak fuel into the shell and then flow into the aircraft. I realized what was happening and rotated the exterior vent in order to obtain a slight positive pressure, thereby keeping the bladder inflated within the metal shell.”

“We informed maintenance of our fuel experiences and how we fixed it. No other aircraft then experienced this fuel problem and Transocean safely ferried 157 C-46s to Shanghai.” According to Captain Kennedy’s log book, he flew 9 more C-46s to Shanghai, ending with his last trip on September 6, 1948. Transocean logged over a million and a half miles over the Pacific Ocean en route to China. There was only one later incident. The 148th Commando lost an engine 400 miles offshore from Oakland but returned on its remaining engine for repairs before completing the trip.

Transocean’s pilots were modern day swashbucklers. Young and daring, most were in their 20s, yet they were tough and capable, with professionalism unequaled by their contemporaries of the scheduled airlines. Most had been seasoned by war. They took on any challenge, blazed new air routes, sometimes landing where no other large aircraft had been, and set speed records as a matter of course.

I hope you have a good weekend and remember to keep family and friends close. Life is unpredictable and as I have said before: “Job security as a professional pilot is a myth even in the best of times.”

Robert Novell

May 30, 2014