The Forgotten Aviators of 1919 – December 11, 2015

Today Is The Day – December 7, 2015

December 7, 2015

Now You Know The Rest Of The Story – December 18, 2015

December 17, 2015Robert Novells’ Third Dimension Blog

December 11, 2015

Good Morning and Happy Friday,

Dozens of people had flown the Atlantic Ocean by 1927 but when Lindbergh made his historic nonstop flight we forgot about all that went before him. So what was so special about Lindbergh’s flight? Well, it was the longest, nonstop, heavier-than-air, transatlantic flight, it was the first solo crossing, and his flight finally fulfilled the difficult specific conditions of the Orteig prize of $25,000.00 which had been up for grabs since 1919. However, the first transatlantic flight was actually made in May 1919 from New York to Plymouth, England and the specifics of this event is our topic today.

The First Flight Across the Atlantic

Written by Commander Ted Wilbur

(Smithsonian Institution, National Air and Space Museum, Washington D.C., 1969)

In 1917, fully engaged in “the war to end all wars,” the United States was concerned about antisubmarine warfare. Transport of suitable bomber planes from America to Europe was a risky business. Ironically, ships carrying aircraft capable of combating U-boats were being sunk by submarines. One officer regarded the transaction as a “masterpiece of insanity.” Besides, although production of patrol seaplanes was on the upswing, deck space and shipping holds were at a premium; human cargo and essential equipment had priority. As a solution, the Navy decided to build its flying boats large enough to cross the Atlantic under their own power. Operating from European bases, they would then obviously have sufficient range to reach the center of German submarine activity. However, at this time the longest nonstop flight accomplished was about 1,350 miles, flown under ideal conditions and in the vicinity of a landing field. (In 1914, the German aviator Boehm had remained aloft 24 hours on what was actually an endurance flight.) The suggested route across the Atlantic was over 1,900 miles, over an area not well known for ideal flying weather: Newfoundland to Ireland.

The idea, even in 1917, really wasn’t far fetched. Nor was it new. The challenge had existed for years and, as early as 1910, attempts were made to cross the Atlantic by air. First, there were balloons, nonrigid airships, successful only in provoking interest. Then, prompted by foresight (and good business sense), England’s Lord Northcliffe threw down his gauntlet. With a vast string of publications, Northcliffe was the British William Randolph Hearst Possessing a taste for aeronautical events and a keen understanding of the portents of the aeroplane, the perceptive lord pronounced a prize of 10,000 pounds for the first successful trans-Atlantic flight. He published his decree and the conditions for the $50,000 competition in his London Daily Mail on April 1, 1913. The award would go to the first aviator to cross the Atlantic by plane, either way, between the North American continent and any point in Great Britain or Ireland, within 72 consecutive hours. The aeronaut was required to complete the trip in the same craft in which he started. Intermediate stoppages would be permitted only upon water and, if the pilot had to go aboard ship during repairs, he would resume his flight from approximately the same point he went on board.

Following the Daily Mail’s sensational announcement, French and Italian aviators were quick to enter the lists while, in America, Rodman Wanamaker, heir to the Philadelphia mercantile fortune, revealed a contract with Glenn Curtiss to build a large flying boat. Glenn Hammond Curtiss, who had been the first man to successfully fly an airplane from water, had harbored a consuming desire to fly the Atlantic before anyone else. To assist him in his long-awaited project, the Navy sent an advisor to the Curtiss plant at Hammondsport, N.Y. The young officer, Lt. John H. Towers, Naval Aviator #3, had been taught to fly by Curtiss. They were close friends. The craft was to be named America and, for a while, it was presumed the pilots would be Curtiss and Towers. However, under pressure from his wife, Curtiss had greatly restricted his personal flying activities. He suggested that a Navy man be placed in charge and that Towers should be plane commander. The Navy Department flatly refused. Trouble on the Mexican border might require the use of aeroplanes. Towers was put on recall alert. He would be permitted to continue in an advisory capacity, but trans-Atlantic flight was out of the question.

Work on Curtiss’ dream progressed. The $500 entry fee was posted. Towers’ place was taken by one of the finest pilots in England, John Cyril Porte, lately of the Royal Navy. Porte had been invalided out of submarine service when he contracted tuberculosis. On expectation of a short life, he had taken up flying and did very well at it. By late July 1914, Towers had gone off to Tampico, the America had completed her trials, and Cyril Porte was ready to go. August 15th would be the date. On August 3, Germany declared war on France, the next day on Great Britain. World War I was on: the America was sold to England as a prototype for 50 patrol seaplanes; Cyril Porte devoted his attention to the Royal Naval Air Service; the transatlantic flight was off; the London Daily Mail’s prize was postponed.

On September of 1917, the chief of the Navy’s Construction Corps, Admiral David W. Taylor, called in his key men, Commanders G. C. Westervelt, Holden C. Richardson and Jerome C. Hunsaker. These Naval Constructors were ordered, in effect, to create what the combined efforts of England, France and Italy had been unable to achieve in three years of war: long-range flying boats capable of carrying adequate loads of bombs and depth charges as well as defensive armament sufficient to counteract the operations of enemy submarines. After the meeting, Glenn Curtiss was summoned. Within three days of his Washington meeting, Curtiss and his engineers submitted general plans based on two different proposals: one was a three-motored machine, the other a behemoth with five engines. Both were similar in appearance, but they opposed conventional flying boats of the period in that the hulls were much shorter, vaguely resembling a Dutch wooden shoe. The tail assembly, for which there were several alternates, was to be supported by hollow wooden booms rooted in the wings and hull. This tail, twice the size of an ordinary single-seat fighter aeroplane, would be braced by steel cables and was situated high enough to remain clear of breaking seas during surface operations. It also permitted machine gun fire directly aft from the stern compartment without the usual danger of blasting the controls to pieces.

This interesting concept had been embodied in a previous Curtiss design for a “flying lifeboat.” The keys to success lay in two factors: a seaworthy hull which had good “planing” characteristics and reliable engines which provided sufficient power for their weight. The entire machine, of course, had to be relatively light, yet strong enough to withstand the severe treatment frequently encountered at sea. It was not practical to build larger and larger airplanes and keep adding more engines to keep the whole affair in the sky unless the load-carrying potential also increased. This “useful load” included crew, fuel, equipment, accessories and armaments things not part of the basic aeroplane. Thus, the plan for the smaller, three-engined aeroboat was decided upon, and the light Liberty engine solved the power problem.

In view of the immediacy of the problem, Chief Constructor Taylor knew he had to cut corners. Under normal circumstances, development of a flying war machine, the engines, hull, wings, fittings and armaments, would require study and sanction by respective divisions within the Navy, a time-consuming process. Admiral Taylor centralized the project. A design contract was let with the Curtiss Company, and Commanders Westervelt and Richardson were sent to the Buffalo plant. Without red tape, the Navy engineers would work closely with the Curtiss people at full speed. One of the first problems readily resolved was the plane’s name. At first, Westervelt applied the initials of his boss: DWT. A little reflection brought realization that Taylor might take a dim view of that, so Westervelt changed it to “Navy-Curtiss Number One,” or simply, “NC-l.” . . .

In just one year from the time they started, the Navy-Curtiss team had met with success: the Nancy flew. Richardson’s fears were allayed; he’d had a mild case of buck fever. His design was vindicated, more than he had hoped for. Soon the NC-1 would establish a record by carrying 51 men aloft, including the first deliberate stowaway in aviation history. But on the 11th of November, World War I ended, and with it the need for a long-range, antisubmarine flying boat to do battle with the Hun. Not long afterward, the $50,000 London Daily Mail enticement was revived.

Within the Navy, there had been growing interest in the trans-Atlantic flight. On the 9th of July 1918, Lt. Richard E. Byrd, a Naval Aviator engaged in the study of crashes at Pensacola, had written to Washington, “It is requested that I be detailed to make a trans-Atlantic flight in an NC-1 type of flying boat when this boat is completed.” His request had been forwarded, with approving endorsement, by Byrd’s commanding officer. Two weeks later he was in Washington where, with mixed emotions, he accepted orders sending him to Nova Scotia as Commander of U.S. Naval Air Forces in Canada. His disappointment at not being assigned to the trans-Atlantic flight was tempered by instructions to seek out, on the coast of Newfoundland, a rest and refueling station suitable for the handling and maintenance of large seaplanes! With the help of a close friend, Ltjg. Walter Hinton, Byrd spent every spare minute on navigational problems associated with a flight across the Atlantic. He thought there might yet be a chance to join the team. But someone else was ahead of him.

John Henry Towers was the third officer to be designated a Naval Aviator. Going into flying at a time when air- planes were regarded as toys dangerous to both life and a Navy career, Towers was a pioneer. As a passenger in 1913, while ticking around at 1,500 feet in a primitive contraption of bamboo, cloth and wire, he encountered a violent gust which threw the machine out of control and hurled its pilot to his death. As the frail little seaplane plummeted earthward, Towers was caught in the wires. He clutched the wooden frame, hanging on for dear life. Somehow, just before striking the waters of the bay, the wings levelled, and the fledgling aviator found himself emerging from the wreck, wet but unhurt. His suggestion that safety belts be used in aeroplanes was noted and approved. Towers’ career covered the early period of aviation development in the Navy. As a close associate of Glenn Curtiss, he had been a natural choice for participation in the abortive 1914 plans for the trans-Atlantic flight of the America. In 1916, after diplomatic duty in London, Towers was ordered to Washington where he had little time to think about flying the Atlantic, that is, until the design for the NC boat came to his attention. At first, he didn’t care for its unconventional appearance. The short hull looked a little queer and he disliked it. But the fire was rekindled; Commander Towers requested assignment to the project as officer-in-charge. . . .

All told, there had been nine British entries posted for the Daily Mail’s prize, but the two already at St. John’s seemed a good bet. Harry Hawker and Royal Navy LCdr. Mackenzie Grieve had a Sopwith; Captains Raynham and Morgan a Martinsyde. Both aircraft were single-engined biplanes. They announced their intentions to fly directly to Ireland. The only thing delaying them was poor weather. Foreign skepticism greeted the Navy’s insistence that its interest was solely of a scientific nature. To the Europeans it was obvious that America wanted to be first, in spite of the diplomatic overtures about sharing ships and whatnot. The Navy’s statement that the NC program was simply a “development of a wartime project” was derided by the press. Actually, when Lord Northcliffe re-established the prize after the war, the rules had changed a bit. No longer were “ocean stoppages” permitted and “machines of enemy origin” were barred. Thus the NC’s and the giant German bombers, respectively, were neatly eliminated. Furthermore, the United States had made no attempt to file an entry fee, and the American crews were forbidden to accept any possible prize money, even if offered – or earned. It was to be just a well-organized, all-Navy endeavor.

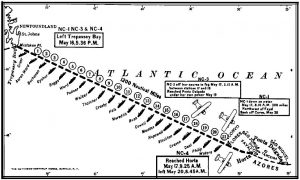

Credence was lent to this announced policy when, in an unprecedented ceremony on the third of May, the three flying boats were placed in regular Navy commission, just as if they were ships of the line. John Towers formally assumed command of NC Seaplane Division One. His orders, signed by Franklin Delano Roosevelt, acting Secretary of the Navy, gave Towers a status roughly equivalent to that of a destroyer flotilla’s commander. Towers chose the NC-3 as his “flagship” and then made the crew assignments for which so many had waited so long. Richardson was to be chief pilot of the NC-3. Naval Aviation pioneers Patrick N. L. Bellinger and Albert C. Read were detailed to the NC-l and NC-4 respectively. Walter Hinton was to be one of the pilots of the NC-4. A lieutenant commander named Marc Mitscher, who had originally been slated to command the NC-2, was to be a pilot of the NC-l. LCdr. Richard E. Byrd was ordered to go aboard the NC-3 with Towers, but to proceed only as far as Newfoundland. Meticulous as the planning had been, the Navy was taking no chances. There was an extra card up its sleeve – a long-range airship. The C-5, a non- rigid gas bag with an open-cockpit, power/control car slung beneath, may have been ungainly in appearance, but it was capable of travelling long distances through the air. Recent experience had indicated it could easily reach the Azores and, likely enough, the continent of Europe. The C-5 was ordered to proceed to St. John’s where her commander would be joined by LCdr. Byrd who would navigate her across the Atlantic. . . .

A native of New Hampshire, LCdr. Albert Cushing Read was an observant man, small of stature, conservative in his ways and economical with words. Friends called him “Putty,” an unlikely nickname of obscure origin. One story has it that the monicker was earned when he came back from a summer vacation sporting a pallid complexion instead of a suntan. At any rate, the five-foot-four, 120-pound New Englander certainly knew how to express himself with effect; in January 1918, he had married Bessie Burdine, a young lady whose family owned Miami’s largest department store. While quiet to the point of reticence, he could be articulate when necessary. Graduated from the Naval Academy with honors, he soon became one of the Navy’s best officers. As Naval Aviator #24, he was known as a brilliant pilot and navigator. The Navy was his life, the NC-4 a pivot point. The trio of giant flying boats had departed Rockaway in a “V” formation beneath leaden clouds: the “flag- plane” NC-3 was flanked on the right by the NC-l and on the left by the NC-4. As the group made a sweeping turn around the air station and took up heading for Montauk Point, in the flight suit pocket of each crewman was a somewhat withered gift, a four-leaf clover – farewell gestures from Aviation Director Irwin. The gruff old Captain had brought them to the station on the 3rd of May. Now he stood below, sternly watching a year and a half’s work drone slowly out along the coast, headed for the jump off point in Canada. Soon they were lost to view. . . .

As the formation moved eastward, the navigators busied themselves with Byrd’s inventions and made computations. At noon Read made a note in his log: “Passing Montauk Point. Sun came out.” He was feeling pretty good. From his position in the bow, he could see Towers in the lead plane and, several hundred yards beyond, Pat Bellinger in the NC-l. Both seaplanes stood out clearly, yellow wings shining brightly against the blue waters of the ocean below. Looking aft along the hull, he could see the helmeted heads of his pilots, Stone and Hinton. Lt. Elmer Stone was the pioneer aviator of the Coast Guard. During the war he had been a test pilot, his performance earning him a place on the trans-Atlantic list. Ltjg. Walter Hinton was formerly an enlisted man. His skill in handling flying boats qualified him for the NC-4. Normally the two pilots would take turns at the controls, each spelling the other at half-hour intervals. But when rough air was encountered, it would take the strength of both men to keep the massive plane on course. Hinton had made the takeoff from Rockaway, and it was agreed to swap positions for each leg of the trip. The first landing was to be at Halifax. From there they’d go to Trepassey Bay, near St. John’s, the jumping-off spot for the big effort. They had turned a little northward after Montauk Point, heading toward Cape Cod. At 12:30 Chatham Naval Air Station out on the Cape radioed a message:

“DELIGHTED WITH SUCCESSFUL START. GOOD LUCK ALL THE WAY.” – ROOSEVELT.

Assistant Secretary of the Navy Roosevelt had long considered the NC’s his pets. He had encouraged the project every step of the way and had given all possible support. In April, while Josephus Daniels was in Europe, accompanying President Woodrow Wilson at the disarmament talks, Roosevelt had made a quick trip to Rockaway, eagerly seeking a ride in one of the big boats. The weather was not the best that day, the men were nearly worn out from constant work, but Richardson took him up in the NC-2. It was a rough, bumpy flight, with FDR crouching just behind the pilot. When he got back on land, he was slightly green but full of enthusiasm. And now, on the NC-4, one of his school classmates and boyhood friends was the engineer, Jim Breese. Lt. James Breese had also been a test pilot during the war. But it was his experience as a power plants expert, especially on the Liberty engine, that put him on the team. His assistant was Chief Machinist’s Mate Eugene Rhoads. “Smokey” Rhoads, who had replaced the unfortunate Chief Howard, was reputed to be one of the best engine men in the Navy.

Filling out the crew was Ens. Herbert Rodd, an experienced radio operator who had helped in the development of the direction-finding compass. The ensign was a good man with a radio; he was now getting remarkable results with the long-range transmitter. But he was having trouble talking with the man 30 feet away. Read’s intercom was out. Standing in the bow, he was waving futilely at his pilots who seemed not to understand what it was he wanted. The NC-4 was falling far behind the other two planes, and he’d been motioning for more speed. They had passed Cape Cod and were now over open sea on the way to Nova Scotia. Read lowered himself into the hull to go back to the pilots when Jim Breese arrived to tell him they’d had to kill the center pusher engine owing to dropping oil pressure. The plane could fly well on the three remaining engines, so they decided to continue, informing Towers of the situation. At 2:05 P.M., they passed through hazy air over the first of the “station” destroyers, the McDermut.

Right on course, Read could barely make out the other NC’s miles ahead. He had a slightly uneasy feeling as he headed for the next ship, 50 miles further on. Halfway there, a geyser of water and steam suddenly erupted from the forward center engine, and Read watched a connecting rod sail out of the crankcase and off into space. Now they’d have to go down. Crawling to the pilots, Read yelled to turn into the wind and land. Rodd was busy with his radio. The distress call got through. Towers and two destroyers heard it. Although the other planes continued on, they had seen the flash of wings as Hinton made the turn and assumed Read was going back to Chatham. They had not seen the NC-4 descend. The water surface was calm enough for a safe landing but, once down, Rodd couldn’t get through to anyone; the destroyers were too busy talking to each other. He couldn’t be heard on the long-range radio, and the short-range transmitter was on a frequency different from the ships’ receivers. In the haze, a searching destroyer passed within ten miles of the floating seaplane without spotting her. A little discouraged, Read soon found himself in the middle of an empty sea, about 80 miles from the nearest land, with night coming on. There was nothing else to do but start taxing with the two good engines left. He hoped they would hold out. After dark the moon came up and they had a fairly pleasant ride. The engineers and pilots took turns at the controls and Read even got a little sleep. Towards dawn they tried to chase a passing steamer but only succeeded in losing another engine. For 20 minutes Breese and Rhoads worked on it while the NC-4 made circles in the ocean. Finally finding the right combination of cuss words to unlock the secrets of a recalcitrant Liberty, they were underway again. At dawn they were just off Chatham as two seaplanes took off from the air station to join in the search. They didn’t have far to look.

Read’s “shakedown” had turned into a breakdown. Headlines announced the incident which, when added to the NC-4′ S past misfortune, gave rise to her new name: the “Lame Duck.” Within two days one bad engine was replaced, the other repaired. But once again the elements were against them; a gale set in and a 40-knot northeaster held them in the Chatham hangar till the 13th. Public indignation was aroused. A lot of taxpayers’ money was supporting a vast fleet of station ships waiting idly at sea. Read was frustrated, but during this period he received some encouragement from the northern weather dispatches. Conditions on the Newfoundland-Azores route were so bad that the NC-l and NC-3 weren’t going anywhere, either. When the NC-4 had been lost to sight and its distress call intercepted, Towers assumed it would either land by the McDermut for repairs or return to Chatham, so he kept on. During the afternoon, he and Byrd kept busy in the NC-3’s cramped forward compartment, trying out the sextant, dropping smoke bombs and making calculations with the drift indicator. During the trip north, both planes were in and out of squalls. Hot and cold air rushing over headlands toward the sea combined to form a vicious mixture. The strain of handling the big boats was taking its toll on the pilots, especially Dick Richardson who was over 40 years of age. Buffeted by gusty winds, the Nancy’s pitched and yawed, and it took the constant efforts of the pilots to remain on course. The final three hours were the most severe but, upon arrival over Halifax, they were rewarded with a wondrous view. A beautiful rainbow extended from a hilltop to the clouds 6,000 feet above. Beyond the brilliant band, a rich red sunset tinted the fading colors of the rolling landscape with a crimson glow. Cheering crowds and factory whistles added to the glamour as the NC’s taxied to their moorings.

Upon arriving in the Canadian port, Towers was disturbed to hear of the apparent loss of the NC-4, but he knew the sea conditions had been good and had no fear for the safety of Read and his crew. Hence the news of their “rescue” the next morning came to report their activities. Some reporters lived in remodeled railroad car (right). Had conditions improved sooner, either at the Azores or over the north Atlantic route to Ireland, U.S. or British teams would have been on their way and the delayed “Lame Duck,” NC-4, might have lost its chance to be first across Atlantic. It was no surprise, and he set about repairing minor damage to his own plane. Cracked propellers were a problem, but with the help of wartime friends of Byrd, exchanges were achieved.

On the 10th of May they were off again. Still the air was rough and now quite cold. To his annoyance, Richardson aboard the NC-3 found his arms muscle-bound from the exertions of two days before, and he was slow in his reaction on controls. His copilot, McCulloch, assumed the load until he had the kinks worked out. Following the line of station ships, the NC-3 passed Placentia Bay and the men sighted their first icebergs. From 3,000 feet, Richardson noted they had the appearance of majestic steamships, but that their intense whiteness gave betrayal. “Around each berg,” he later wrote, “the water was illuminated by reflected light from submerged portions, presenting a particularly arresting appearance – like that of the sun shining through the back of high breakers running in on the beach.” Dick Richardson always enjoyed things like that.

As they approached Trepassey Bay, a gradual descent was made. The air was gusty and the shocks were more violent as they neared the surface and came closer to the barren land. Strong swells were rolling as they touched water near Powell’s Point. To get within the bay, Richardson kept the NC-3 skimming at high planing speed – careening, bouncing, slipping through “an avalanche of wind which rushed across the harbor from the bluffs.” With goggles fogged by salty spatter, he couldn’t see the water clearly and consequently mistook the spraying wake of a speeding boat, which raced beyond in welcome, for an iceberg. He had visions of floes all around him and “would not have been surprised had one come crashing through the hull at any moment.” Bellinger experienced the same conditions. By evening both NC’s were safely tied up near the base ship, USS Aroostook.

It had been an interesting day. Dreary windswept Trepassey Bay hadn’t seen so much activity since the times when sinister ships made use of the harbor’s haven. To the British teams, 60 miles across the hills, over at St. John’s, it might well have seemed that pirates were again abroad in those waters – with Lord Northcliffe’s prize at stake. The members of the press enjoyed the situation. North Atlantic weather was still delaying an English start so, once the reporters realized the Americans meant business, they for- sook their favorites, Hawker and Grieve, and moved their camp from the comfortable surroundings of the Cochrane Hotel in St. John’s to the windy, forlorn wastes of Trepassey. Not that it was all that bad. They acquired a railroad dining car, outfitting it with a stove, table, cots and a cook. This they had hauled down to Trepassey as living quarters. On its side they painted the name, NANCY-5. The Aroostook was the mother ship of Seaplane Division One. Since each NC crew member was limited to five pounds of personal luggage, the Aroostook, carrying all their clothes and extra articles, would follow them to Plymouth. Towers and Richardson, being the senior officers, were assigned the ship’s pilot house as sleeping quarters. It had even been fitted out with two brass beds. Towers noted that since the room was mostly glass-sided, they had the privacy of the proverbial goldfish bowl. Nevertheless, while waiting for the Atlantic weather to clear up, they had a comfortable time of it.

Commander Towers had been, since 1914, the driving force and guiding genius of the plan to cross the Atlantic in an American airplane. NC-3 entered harbor of Ponta Delgada in the Azores on May 19, 1919, after Towers and his crew had sailed 205 miles through varying sea conditions. On the 18th, weather was still so bad that Read and his men were forced to stay in Horta. In spite of gala celebrations and congratulatory messages from around the world, Read was concerned. There had been no word of Towers. On top of that, disturbing news came through from Canada. The British had made their move. Stampeded by Read’s successful flight to the Azores, Hawker and Grieve set out to head off the Americans. During the afternoon, they had taken off from St. John’s, jettisoning their Sopwith’s landing gear to gain speed for the run to Ireland. An hour later, Raynham and Morgan tried to follow but their Martinsyde couldn’t make it off the field. They crashed and Morgan was seriously injured. By the next day, Hawker and Grieve had vanished over the North Atlantic. In view of the gallant effort, all England mourned and Lord Northcliffe donated the $50,000 as a consolation prize to the flyers’ widows. On the 19th of May, a U.S. Marine battery stationed in the hills west of Ponta Delgada sighted something out to sea. As the destroyer Harding moved to lend assistance, John Towers stood in the heaving remnants of the NC-3 and shouted, “Stand off! We’re going in under our own power!” He and his crew had sailed the cracked and broken boat 205 miles, backwards, through violent seas to their destination. He didn’t need help now. In spite of Towers’ fantastic achievement, LCdr. Read was the popular hero. And so it came to be that when the NC-4 continued on to Lisbon and thence to England, Towers was not on board. Now, when a fleet commander has his ship shot out from under him, he transfers his flag to another. The circumstance was parallel in Towers’ case. Roosevelt thought so. But Josephus Daniels did not agree. Even when the question was raised on the floor of Congress, Secretary Daniels stood fast in his conviction that since Read had made it to the Azores in the NC-4, he should continue as her sole commander. Towers was forbidden even to ride along as a passenger; he was ordered to proceed to Plymouth aboard a destroyer. It was a bitter pill for the man who was Commander of U.S. Seaplane Division One, a chief planner and organizing genius of the expedition, and it was a keen disappointment to the other members of the group, including Albert Read.

“We are safely across the pond. The job is finished!” – LCdr. Albert C. Read

The rest is history. Read arrived in Lisbon harbor at twilight on May 27, 1919, the first man to cross the Atlantic by air. He “finished the job” four days later as the NC-4 landed at Plymouth. The last leg had been planned for “sentimental” reasons. Later, in London, he was pleased to grip the hand of Harry Hawker. The two British flyers had been forced down in the mid-Atlantic but managed to ditch near a passing ship. Lack of a wireless had postponed news of the rescue for several days. The excitement over the flight of the NC-4 soon faded. Within two weeks the British team of Alcock and Brown accomplished what Hawker had set out to do. A month later, the dirigible R-34 flew from Scotland to New York – and then returned to England. More flights followed, including Dick Byrd’s, his dream of flying the Atlantic finally come true. And for the men involved with the NC project, the future held divergent paths. Glenn Curtiss, who had done so much for the development of aircraft in America, wearied of his courtroom battles with attorneys of the all- encompassing Wright aero patents. He moved to Florida where his investments in such holdings as Hialeah and Opalocka paid handsome dividends: in five years, more than he had ever made in building airplanes. Jim Breese, too, became a successful businessman, and Walter Hinton left the service to find adventure on the Amazon. Most of the others stayed with the Navy, completing lengthy and, in some cases, illustrious careers. Bellinger, Byrd, Mitscher, Read and Towers all achieved flag rank. During World War II, Mitscher’s work with Task Force 58 earned him the title of “Admiral of the Marianas.” Later, Towers became Commander of the Pacific Fleet.

Lots of information in today’s post and yes, it was a little longer than usual; however, I hope you enjoyed this trip back in time and when time permits view the video below which recaps the events we have talked about today.

Have a good weekend, enjoy time with family and friends, and remember to use the following two words often during the coming days – MERRY CHRISTMAS – because these words are about family and friends…..not politics or religion.

Robert Novell

December 11, 2015