Who Was the First Pilot to be Shot Down During the Vietnam Conflict – January 29, 2021

Jim Raisbeck – Innovator – January 22, 2021

January 23, 2021

The Stratofortress is Like the Energizer Bunny….It Just Keeps Going, Going, and Going – February 5, 2021

February 7, 2021RN3DB

January 29, 2021

Good Morning,

For most people the Vietnam War is a distant memory, much like the Korean War, but today I want to go back to 1954 and tell you the story of “Earthquake McGoon……a man who always had a warm smile for all he met and a dedicated aviator who gave his all to the cause.

Enjoy…..

The Shootdown of “Earthquake McGoon”

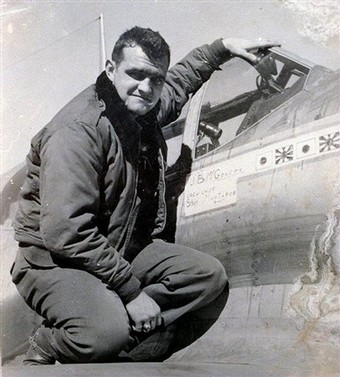

James B. McGovern, Jr. was born on February 4, 1922, in Elizabeth, New Jersey. Growing up, his brother recalled in a 1999 interview that, “I didn’t know what I wanted to be, but all he ever talked about was becoming a pilot,” he said. Having graduated high school in 1940, the young McGovern got a job working at Wright Aircraft Engineering Company in Patterson, NJ, and trained at the Casey Jones School of Aeronautics. After the United States entered World War II, the five-foot nine-inch tall, then-180 pound, aircraft mechanic enlisted in the Army Air Corps on May 21st, 1942, to learn to fly.

Arriving in China in November of 1944, James McGovern joined the 14th Air Force – 23rd Fighter Group’s 75th “Tiger Shark” squadron, part of the Flying Tigers volunteer group. He was credited with shooting down four Japanese Zero fighters and destroying five on the ground.

At war’s end in 1945, Major General Claire Chennault, founder of both the Flying Tigers and the 14th Air Force, recruited McGovern and other veteran pilots for his next enterprise, a commercial airline called Civil Air Transport (CAT). Under contract to Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalist regime, CAT flew civilian and military missions during China’s civil war, and would later help evacuate thousands of refugees to Taiwan before the Communist victory in 1949.

Having bulked up during the war to 260 pounds, the ex-fighter pilot liked the roomy cockpits of CAT’s war-surplus C-46 transports but still sometimes used a wicker chair instead of the standard pilot’s seat.

A saloon owner and ex-sailor, Ed F. Gingle, but known to most in the Orient as “Pop”, dubbed the big aviator “Earthquake McGoon”, after a hulking hillbilly wrestler character in the then-popular “Li’l Abner” comic strip. “It didn’t bother him. He was a character himself, and I think he thrived on it,” John McGovern, his younger brother, said.

However, during a flight in December of 1949, McGovern ran out of fuel, made an emergency night landing in a riverbed and was captured by Chinese Communist troops. When he turned up safe six months later, other pilots joked that his captors “got tired of feeding him.” But McGovern had argued his way out, saying “You keep saying you’re going to release me but you haven’t, so I don’t believe anything you say. You’re liars.” So, the Chinese soldier let McGovern go free in May of 1950.

Civil Air Transport moved to Taiwan in 1949 and a year later was secretly acquired by the CIA, which continued its commercial service as a cover for clandestine activities.

The First Indochina War…

In 1953, France asked the administration of President Dwight Eisenhower for American help in fighting a Communist rebellion in colonial Indochina. Soon, CAT was there, flying supply missions with French insignia painted over the company logo.

Wallace “Wally” Buford, who had flown B-24 bombers during World War II and C-119s in Korea, and a recipient of two Distinguished Flying Crosses and the Purple Heart, was studying for an engineering degree in 1953 when he saw a notice that the government was seeking experienced C-119 pilots. So, he signed up.

A year later, McGovern and Buford, 28, were among two dozen Americans who earned about $3,000 a month air-dropping supplies to the besieged French garrison at Dien Bien Phu. On May 6, 1954, their unarmed C-119 Flying Boxcar, #149 (originally U.S. Air Force tail number 49-149, as it was on loan to the French Air Force from the USAF’s 314th Troop Carrier Wing), and five other C-119s, took off from Haiphong’s Cat Bi Airport. McGovern’s plane was carrying a parachute-rigged Howitzer artillery piece to aid the French soldiers at Camp Isabelle – the southernmost firebase of Dien Bien Phu.

On May 6, 1954, their unarmed C-119 Flying Boxcar, #149 (originally U.S. Air Force tail number 49-149, as it was on loan to the French Air Force from the USAF’s 314th Troop Carrier Wing), and five other C-119s, took off from Haiphong’s Cat Bi Airport. McGovern’s plane was carrying a parachute-rigged Howitzer artillery piece to aid the French soldiers at Camp Isabelle – the southernmost firebase of Dien Bien Phu.

The first aircraft in the flight, flown by Steve Kusak, safely dropped its load on Isabelle. But as McGovern approached the drop zone, however, his aircraft was hit twice by 37mm anti-aircraft fire, in both the left engine and stabilizer. “I’ve got a direct hit,” other pilots heard McGovern say.

Immediately, the French crew of “kickers” in the aircraft’s rear, named Jean Arlaux (on his first combat mission), Bataille, Moussa (a Malayasian), and Rescouriou, dropped their cargo, as McGovern shut down the burning engine, and climbed over the mountains surrounding the fort.

With one engine afire, McGoon nursed the aircraft another 75 miles southward, into Laos. Approaching 4,000-foot mountains, he radioed fellow C-119 pilot Steve Kusak for help in finding level ground. “Turn right,” said Kusak, who was directing McGovern towards an airstrip near the Nam Ma River.

Forty minutes after being hit, McGovern made his last radio transmission, “Looks like this is it, son.” His crippled C-119 Flying Boxcar cartwheeled into a Laos hillside near the Sang Ma river in Houaphan Province. The crash killed McGovern, Buford, and two of the French crewmen instantly. But two of the cargo handlers, French Lieutenant Jean Arlaux and Private Moussa, were thrown clear and survived, but were captured by the Vietminh. Moussa died a few days later of his injuries.

McGovern & Buford were the first two Americans to die in combat in Vietnam. The day after the crash, the garrison at Dien Bien Phu surrendered, ending the 57-day siege. No effort were made to recover McGovern or Buford’s remains then.

In the May 24, 1954, edition of Life magazine, an article called “The End for Earthquake” ran, detailing the pilot’s shoot-down, and displaying photographs that would become all to common in the years of conflict that would follow.

Years of Silence…

After a French officer learned from Ban Sot villagers in 1959 about three graves in the area, CIA officials stifled his report. “They indicated in a vague way that they feared a lawsuit if they gave the relatives false information. Therefore, no one notified McGovern’s or Buford’s relatives,” according to Felix Smith, a retired CAT pilot.

Smith recalled McGovern as being “a real big-hearted guy,” but not the “wild man” as the press widely reported. “He was a bon vivant, happy-go-lucky. He loved kids, and he was the guy who in a tense situation would come out with some joke.”

The search for McGovern’s remains came to light again in October of 1997, when a “Joint Task Force-Full Accounting” team investigating an unrelated crash near Ban Sot saw an old C-119 propeller in the village. It was assumed to be French in origin, until William Forsyth, the agency’s top researcher, heard about McGovern from a former pilot, and began to search for old news clippings about the crash.

A year later, Forsyth, whose specialty is aerial photo analysis, spotted three “probable graves” in a 1961 photo of the Ban Sot area. But with Vietnam War MIAs taking precedence, officials moved “Case 3036”, as it was called, to the back burner with other “Cold War losses.”

There it stayed until a group of ex-CAT pilots, led by Felix Smith, launched a letter-writing campaign, and lobbied Congress and former intelligence officials, to have the case upgraded for immediate action. Retired spy Dudley Foster, who once served in a liaison role with CAT, persuaded George Tenet, then the director of the CIA, to back the effort.

With “Case 3036” given new priority, task force investigators revisited Ban Sot, where in July of 2001, they interviewed four witnesses to the 1954 crash and three who pointed out burial sites. Skeletal remains were discovered in an unmarked grave in northern Laos in December of 2002.

Phimpha, a 65-year-old Laotian farmer, recalled that he was fishing in a river when the plane came down, and later saw three bodies, among them a “very large Caucasian with a round face, still strapped in the pilot’s seat.”

A few days later, Phimpha noticed fresh grave mounds near a road. His wife, Thok, 67, recalled that as a girl she “always ran past that location because of the ghosts thought to be there.”

Belated Honors…

On February 24, 2005, James McGovern was posthumously recognized by the French government, along with his co-pilot Wallace Buford, for their sacrifice. Seven of the other surviving pilots of the Civil Air Transport were awarded the Legion of Honour with the rank of Knight by the President of the Republic of France for their actions to supply Dien Bien Phu during the siege.

The skeletal remains found in 2002 were positively identified in September 2006 as McGovern’s by laboratory experts at the U.S. military’s Joint POW/MIA Accounting Command. He was interred in Arlington National Cemetery on May 24, 2007, in Section 8-M4, Row 11, Site 6.

Enjoy the weekend, take some time to kick back and do nothing, and always keep friends and family close…..life is short.

Robert Novell

January 29, 2021