Upside Down Pangborn…..First to Fly Nonstop Across the Pacific – May 8, 2015

The Downfall of a Man Named Lawson – May 4, 2015

May 4, 2015

Shorts 330/360 – A Regional Airliner Becomes an Army Workhorse – May 15, 2015

May 16, 2015Robert Novells’ Third Dimension Blog

May 8, 2015

Good Morning and welcome back to the 3DB. This week I want to talk about a man who flew the Pacific nonstop but did so with a few not so normal modifications to his airplane. The history of this gentleman was told to me by a friend in Oregon who has visited the small museum, commemorating the crossing of Mr. Clyde “Upside Down” Pangborn and his copilot, and I think you will find the story interesting and unique.

First let’s talk a little about the man they called “Upside Down Pangborn”…………

Clyde Edward “Upside Down” Pangborn was born in Bridgeport, Washington, on October 28th, 1894, and after finishing high school, Pangborn attended the University of Idaho for two and a half years, where he studied civil engineering. In 1917, Pangborn answered a call for volunteers and enlisted in the Aviation Section of the United States Army Signal Corps as a cadet and learned to fly. After working temporarily as a flight instructor on Curtiss JN-4 Jenny, aircraft at Ellington Field in Houston, Texas, he was demobilized in March of 1919.

Pangborn, still interested in an aviation career, decided to pursue professional barnstorming. He began to make his living doing exhibition flying and aerial acrobatics at fairs, dedications, and other public events throughout the West Coast region. He was known as “Upside-Down Pangborn” because of his penchant for slow-rolling planes onto their backs and gliding upside-down. In 1921, Pangborn and partner Ivan R. Gates formed the famous Gates Flying Circus, which performed both throughout the country as well as internationally.

The show was very popular and between 1922 and 1928 Pangborn performed successfully without an accident/incident or personal injury and established the world record for changing planes in mid-air. During this period Pangborn had the good fortune to meet pilot Hugh Herndon, Jr., who would later accompany Pangborn on their famous transpacific flight.

For a complete profile on the man called “Upside Down” visit the National Aviation Hall of Fame where he was enshrined in 1995.

Now, let’s talk about the nonstop flight from Tokyo……………

Clyde Pangborn and Hugh Herndon, Jr.

(First to Fly Nonstop Across the Pacific)

Clyde ‘Upside-Down Pangborn and his co-pilot Hugh Herndon, Jr., were under house arrest in Tokyo’s Imperial Hotel. Charged with espionage and making an illegal flight, they had been detained for seven weeks since landing in Tokyo on August 8, 1931. The two American airmen had strutted onto aviation’s world stage 12 days earlier. They had taken off from New York’s Roosevelt Field in a blaze of publicity, with high hopes of beating the around-the-world speed record set by one-eyed Wiley Post and his Australian navigator Harold Gatty.

Pangborn, a daredevil stunt pilot, was well-known in American aviation circles. He had been chief pilot and half owner of the fabled Gates Flying Circus until it closed down in 1928. His playboy co-pilot, an aviation novice, was better known in society circles. A Princeton dropout who loved the good life, Herndon was the son of Standard Oil heiress Alice Boardman. Anxious to see her son make a name for himself, the socialite had not turned a hair when he asked her for $100,000 to finance the flight.

Their hopes of beating Post and Gatty’s flight time had come to an end in Khabarovsk, Siberia, where, landing in a teeming rainstorm, their Bellanca Skyrocket Miss Veedol had slid off the runway and become hopelessly bogged down. Already well behind their strict schedule, and with no hope of taking off for several days, the despondent pair abandoned their world flight. They decided, instead, to salvage something from the trip by competing for a $50,000 prize offered by Japan’s Asahi Shimbun newspaper for the first nonstop flight across the Pacific. They carried no maps of Japan, so Pangborn cabled the editor of the English-language Japanese Times, asking for a track and distance from Khabarovsk to Tokyo and requesting that the American Embassy obtain landing permission from the Japanese Aviation Bureau.

The field at Khabarovsk had dried out before their cable was answered, so Pangborn decided to take off before it was swamped again by threatening storms. Flying a rough heading for Japan, they received a radio message giving a track and distance and advising that landing approval was being sought. After landing at Haneda to get directions, they finally reached Tachikawa airport, where they were met by angry officials demanding to see their landing papers. Japan was at war with China and, understandably, did not take kindly to foreign pilots arriving unannounced and photographing military-restricted areas. Pangborn recounted: We were arraigned on three counts. That we had flown over fortified areas and that we had photographed these areas. True we didn’t have a flight permit with us, but we assumed it would be routine for our embassy to arrange it. As for flying over fortified areas and taking pictures, we were just tourists taking what we thought were pretty landscape shots.

Their seven weeks under house arrest gave Pangborn and Herndon the time to plan their transpacific attempt. They were also able to consider the efforts of the other teams, Japanese and American, that had already unsuccessfully competed for the Asahi Shimbun prize.

The Japanese decision to sponsor a Pacific flight had been sparked four years earlier by Charles Lindbergh’s transatlantic triumph. Lindbergh’s New York to Paris solo flight had electrified the world. Overnight, the American had become an international hero–the most photographed person of his era. The Japanese believed that the first successful transpacific flight, which was a longer and more demanding undertaking than crossing the Atlantic, would help focus attention on Japan’s emergence as the industrial powerhouse of Asia–particularly if a Japanese pilot and plane were first across.

While the world still bathed in the afterglow of Lindbergh’s success, Japan announced its transpacific intentions. The Imperial Aeronautics Association declared that a Japanese pilot, flying in a Japanese-owned and -manufactured aircraft, would cross the Pacific. Shortly afterward, the Tokyo newspaper Mainichi Shimbun placed an order with T. Claude Ryan for an exact replica of Lindbergh’s long-range monoplane.

Delivered to Japan early in 1928, the Ryan NYP-2 (New York-Paris No. 2) was not purchased to attempt the Pacific flight. The original NYP had been built to Lindbergh’s specification to fly the 3,600 miles between New York and Paris–plus a few hundred extra for safety. The flight from Japan to America’s West Coast required an aircraft with a range of at least 4,500 miles.

Although the Japanese buyers may at first have thought it possible to extend the Ryan’s range, it seems more likely that the aircraft’s role was to act as a design guide for Japan’s Kawanishi Company to construct a similar but much larger, transpacific machine, designated the K-12 Nichi-Bei-Go). Two Ryans were ordered, one as a backup in case of an accident. The project folded, however, when flight testing proved that Kawanishi’s lumbering K-12 had neither the range nor the takeoff performance to make the transpacific flight. Red-faced Kawanishi officials hung one of the expensive white elephants from the factory ceiling beneath a banner proclaiming, How not to design or build a Special-Purpose Airplane.

Interest in the Asahi Shimbun prize did not diminish, even when Charles Kingsford Smith and his crew completed the first transpacific flight from Oakland, Calif., to Brisbane, Australia, in the Fokker F.VII/3m tri-motor Southern Cross in June 1928. The island-hopping flight, which did not qualify for the Japanese prize, was made in three stages; hence, it lacked the drama of a nonstop crossing.

The first nonstop Pacific attempt was made in 1930, when Canadian-born pilot Harold Bromley teamed up with Australian navigator Harold Gatty. Their aircraft was an elegant, 450-hp Wasp-powered monoplane manufactured by E.M. Smith and Company (Emsco) and named City of Tacoma–for the city that had sponsored the flight. Fully loaded, their Emsco had a still-air range of approximately 4,000 miles–500 miles less than they needed. To succeed they would require a tailwind. As this was more likely when flying east, the airmen decided to begin the flight from Japan. Taking off from a long, flat beach at Sabishiro, 370 miles north of Tokyo, they flew 1,250 miles, mostly in cloud, before headwinds forced them to turn back.

Daring young Japanese airman Seiji Yoshihara was the next to try. Yoshihara had made a sensational flight from Berlin to Tokyo in a tiny, open-cockpit Junkers A-50. He figured that the fuel economy of his airplane’s 85-hp engine would enable him to cross the Pacific. Equipping the Junkers with floats, Yoshihara took off on May 18, 1931, following the great circle route. He had covered almost 1,000 miles when the seaplane developed engine trouble, and he was forced to ditch in the Pacific. Miraculously, Yoshihara was picked up by a passing ship seven hours later.

Following Yoshihara’s gallant attempt, the Imperial Aeronautics Association announced additional prize money of $100,000 for a successful flight by a Japanese team. In the United States, a group of Seattle businessmen added a $28,000 sweetener to the $50,000 Asahi Shimbun prize. Their only stipulation was that the flight starts in Seattle and finish in Japan. This meant that prize money totaling $78,000 was now offered for non-Japanese teams–a fortune in those Depression days. It attracted Texan barnstormer Reginald Robbins and oilman Harold S. Jones, who had twice attempted a Seattle-Tokyo flight in their Lockheed Vega Fort Worth. Unfortunately, their shrewd plan to refuel from a Ford TriMotor tanker in the air over Alaska failed to work on both occasions. Another westbound attempt ended when a flier named Bob Wark was forced down near Vancouver, barely 100 miles from his starting point.

Following their aborted flight in 1930, Bromley and Gatty had left the Emsco in Japan to be sold. It was subsequently used in two further American transpacific attempts. The first ended when pilot Thomas Ash failed to get the Emsco off the sands at Sabishiro. For the second attempt, Los Angeles salesmen Cecil Allen and Don Moyle renamed the Emsco Clasina Madge. They took off from Sabishiro on September 8, 1931, while Pangborn and Herndon were still under house arrest in Tokyo. Long on courage but short on experience, Allen and Moyle got lost and, after flying aimlessly for more than a day, landed on Siberia’s Kamchatka Peninsula. The pair eventually headed on toward the United States with stops in the Aleutians and Alaska. The Clasina Madge finally reached Tacoma on September 25, 1931.

Pangborn and Herndon already had been tried in Tokyo’s district court. Found guilty, they were sentenced to 205 days hard labor or fines of $1,050 each. After paying their fines, Pangborn and Herndon revealed their plan to attempt the Japan to United States flight. Because of the recent failures, Japan’s Civil Aviation Bureau had restricted future flights to only approved aircraft. After days of haggling, approval was reluctantly given for Pangborn to attempt one overloaded takeoff from Japan.

They flew Miss Veedol to Sabishiro Beach on September 29 and made final modifications for the flight. Pangborn had worked out a clever plan to reduce drag and extend the Bellanca’s range. The idea had previously been used in 1919 by Australian Harry Hawker in an unsuccessful attempt to cross the Atlantic. The scheme involved removing the bolts holding the landing gear to the fuselage and replacing them with a series of clips and springs attached to a cable. By pulling on the cable following takeoff, Pangborn would jettison the whole structure. For the landing he attached steel skids to the Bellanca’s potbelly.

Pangborn explained: We determined that to make the trans-Pacific flight we would have to take off with the heaviest wing loading [fuel load] we had ever attempted with the Bellanca. Even then it was marginal that we would have enough fuel to take us the 4,500 miles to the U.S. west coast even at the most economical cruising speed. Studying the problem I calculated that we could increase our speed [by] approximately 15 miles per hour if we could rid ourselves of the drag of the fixed landing gear. On a forty hour flight that would be the equivalent of adding 600 miles to our range, and that might make the difference between success and failure.

At Sabishiro Beach the two Americans were guests of the nearby town of Misawa City. The mayor had publicly announced that fliers of any nation seeking such an honorable goal should be hosted in friendship. Not all Japanese were so friendly, however, as the airmen discovered when their painstakingly prepared flight charts were stolen. It appeared likely that the culprits were members of the radically patriotic Black Dragon Society, who for weeks had been violently speaking out against the Americans and their proposed flight.

Pangborn and Herndon obtained new charts and were finally ready to go on October 2. To save weight, they carried no radio, no survival equipment, not even a seat cushion, and limited their food to hot tea and some fried chicken. Even so, with 915 gallons of fuel and 45 gallons of oil on board, the Bellanca was still exceeding its allowable maximum operating weight by 3,400 pounds.

As Pangborn prepared to climb on board the Bellanca, a small Japanese boy rushed out of the crowd and presented them a gift of five apples from his father’s orchard. Pangborn appeared deeply touched. Misawa City, like his hometown of Wenatchee, Wash., was famous for its apples.

Miss Veedol used the takeoff ramp that local villagers had built for Bromley and Gatty’s earlier attempt. A hill of sand had been packed down by a steam roller and then covered with a runway of planks that led down to the beach. Working like a ski jump, its purpose was to give the overloaded airplane an initial burst of acceleration. Even so, the Bellanca had trouble gaining flying speed as it rolled down onto the wet beach.

With its 425-hp Wasp engine screaming at full power, the monoplane was only up to 60 mph with two-thirds of the beach gone. Pangborn had estimated that he required 90 mph for liftoff. As Miss Veedol approached a pile of logs that marked the end of the makeshift runway, Pangborn could be seen rocking the aircraft from wheel to wheel in an attempt to break the drag of the wet sand. He later recounted: I was determined to get off, or pile into those logs. We had permission for only the one attempt and in no way was I going to spend any more time in Japan.

The aircraft staggered into the air with 100 yards to spare. Flying straight ahead, wallowing near a stall, the fuel-bloated Bellanca inched up above the waves. When they had a safe margin of height, Pangborn turned slowly onto a heading of 072 degrees–heading toward the Aleutians.

Three hours out, on track and approaching the Kurile Islands, Pangborn was satisfied that everything was operating normally and jettisoned the landing gear. The main structure fell away but two of the gear’s bracing rods did not drop clear. Pangborn realized that they posed a real threat to a safe belly landing and that he would have to work them free during the flight. Devoid of 300 pounds of landing gear and its drag, Miss Veedol climbed to 14,000 feet, where it picked up a good tail wind.

The sun went down and they began to encounter airframe icing in the clouds. To stay clear of clouds, they climbed to 17,000 feet where conditions were smooth and ice-free. Pangborn decided this was the ideal time to try to get rid of the two dangling struts. Handing over control to Herndon, the steel-nerved airman put his flying circus wing-walking skills to good use. Struggling against the frigid 100-mph slipstream, Pangborn eased out of the cockpit and placed his feet on the broad strut that supported the Bellanca’s wing. Holding on for dear life with one hand, with the other he removed one of the offending brace rods. Pangborn clambered back into the cockpit, warmed himself, and then repeated the procedure on the other side. Through the night it was bitterly cold and he recalled that the water in our canteens, and even our hot tea, froze.

The first real position check was a volcano in the Aleutians, and the two men were delighted to see it loom directly below them. Pangborn remained at the controls, with Herndon responsible for keeping the main wing tanks topped up from the huge auxiliary cabin tank. This required him to transfer fuel with a hand-operated wobble pump. Twice he forgot the task. The first time he was able to pump fuel fast enough to keep the spluttering Wasp engine running. On the second occasion, Herndon’s carelessness nearly cost the men their lives when the propeller stopped dead.

The Bellanca was not equipped with an electric starter. Pangborn had no alternative but to dive the airplane in the hope of getting the propeller to windmill. Yelling at Herndon to start pumping, Pangborn steepened the dive, desperately trying to turn the propeller in the rarefied air. They had lost 13,000 feet and were only 1,500 feet above the ocean when it finally began to windmill and the engine burst into life again.

The only word of their progress during the whole flight came from an island in the Aleutians where an amateur radio operator radioed to America that he had heard an airplane passing over above the clouds. No one was quite sure of their final destination, though Pangborn’s mother was adamant that her son would choose his hometown Wenatchee, Wash., as his landing site. She was among 30 locals who maintained a vigil at its little airfield.

Pangborn sighted the tip of the Queen Charlotte Islands, off the northwestern coast of Canada and knew the worst of the navigation was over. He had been at the controls for more than 30 hours. Aware that the tricky job of belly landing lay not too far ahead of them, he decided to catch a few hours of sleep. He instructed Herndon to hold the current height and heading and to wake him when he saw the lights of a big city. That will be Vancouver, British Columbia, Pangborn yelled.

Once again Herndon’s inattention let them down. When Pangborn awoke some hours later, his cavalier co-pilot had wandered off course and missed both Vancouver and Seattle. Ahead of them was Mount Rainier. Pangborn decided to carry on inland to Boise, Idaho, which would also give them a new world’s nonstop distance record. However, two hours later, when it became evident the Boise area was covered in fog, they turned toward Spokane, Wash. When that destination appeared to be covered by low clouds, Pangborn decided to head for Wenatchee.

At 7:14 a.m. on October 5, 1931, the big red monoplane swooped in over the hills and circled Wenatchee’s little airfield, dumping fuel to reduce the chance of fire. Approaching slowly, Pangborn sent Herndon to the rear of the cabin, hoping that his weight would help hold the tail down during the landing. At the last moment he cut off the fuel and ignition switches and, as the Bellanca flared close to stalling, lowered it gently onto the ground. For a moment it was obscured by a cloud of dust; then, decelerating rapidly, Miss Veedol slithered to a stop, teetered for a moment and fell onto its left wingtip.

After being hugged by his mother and brother, Pangborn was amazed to discover that a representative of Asahi Shimbun was there to present the fliers with their $50,000 check. By some quirk of fate, the newspaper’s emissary had selected Wenatchee as their most likely landing point.

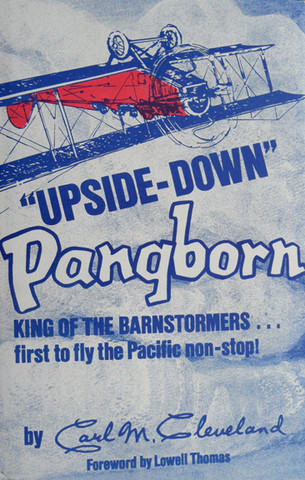

Among the little group that had waited through the night was Carl M. Cleveland, then a young reporter for the Wenatchee Daily World. He had commandeered the only telephone in hopes that he might get a world scoop. He was not disappointed: PANGBORN-HERNDON SPAN PACIFIC….BOY ARE WE GLAD TO GET HERE: PANGBORN PUTS IT….IT’S LIKE A DREAM COME TRUE. Cleveland’s hometown headlines were mirrored around the continent as he passed the story to his editor, who relayed Cleveland’s words to the wire services and the world.

The Asahi Shimbun prize was the only money awarded for the epic flight. As foreigners, Pangborn and Herndon were not eligible for the Imperial Aeronautic Association’s prize, nor did they qualify for the Seattle businessmen’s prize. From Pangborn’s point of view, worse was to follow. His relationship with Herndon was already strained, and their partnership quickly dissolved. Bickering between the two came to a head when Herndon and his mother, as financial backers for the transpacific flight, claimed the prize money and the cash realized from the sale of Miss Veedol. They gave Pangborn a paltry $2,500 for his efforts.

Pangborn vented his feelings in the Albany Times Union. “HERNDON INCOMPETENT SAYS PANGBORN,” blared the headlines. In the story that followed Pangborn disclosed that his co-pilot had known nothing of navigation because he had been romancing a girl instead of studying prior to their flight. He disclosed that Herndon had been little more than a passenger in Miss Veedol, stating, Out of the 200 hours we were in the air [since leaving New York], Herndon flew at most ten of those hours.

The nonstop transpacific flight eventually brought Pangborn other, more lasting rewards. He was honored with American aviation’s prestigious Harmon Trophy–joining other greats such as Charles Lindbergh and Jimmy Doolittle. And news came from Japan that, forgiven for his earlier transgressions, Pangborn had been awarded the Imperial Aeronautical Society’s White Medal of Merit.

The most lasting memento of Miss Veedol’s flight was a gift from Clyde Pangborn to the people of Misawa City. Remembering the touching gift of five apples from the little Japanese boy on Sabishiro Beach, Pangborn arranged for the mayor of Wenatchee to send to his counterpart in Misawa City five cuttings from Washington State’s famed Richard Delicious apples. They were grafted onto trees in Misawa City and, within a few years, cuttings and seedlings were distributed to apple growers around the country. Today, Richard Delicious apples are grown throughout Japan.

A unique story that history has forgotten but if by chance you are ever in Wenatchee, Washington take some time to go into town and visit the museum, dedicated to “Upside Down” Pangborn and his copilot, and the next time you are Japan and the apple you are eating has a familiar taste – take a minute to remember the contributions of Clyde “Upside Down” Pangborn’s contribution to the world of aviation.

Enjoy the video below and have a good weekend; however, remember that life is short. Keep friends and family close, stay true to your profession, and to those Aviators who will follow in your footsteps.

Robert Novell

May 8, 2015