The First Steam Powered Airplane Was a Worldwide Success – Not Exactly. May 20, 2022

Betty Skelton…..Aviation’s Sweetheart – May 6, 2022

May 7, 2022

Who Were The First Test Pilots? – June 3, 2022

June 15, 2022RN3DB

May 20, 2021

Good Morning,

I hope the week was good for one and all and now you will have time for yourself, family, and friends. It has been a long week for me, after going off the grid on a short vacation for four four days and enjoying some quiet time, but I am slowly catching up.

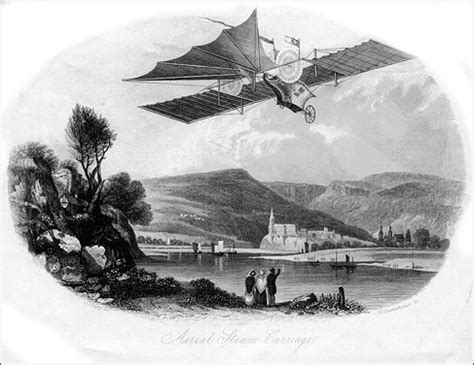

This week we are going to talk about a steam powered airplane that was patented in 1842 and sold to the public as an “Aerial Steam Carriage,” and the next step forward in connecting the cities of the world. Things did not turn out exactly as planned but the way the project was put together rivals modern day public offerings, and marketing, for a new airline.

Enjoy……………………………………

William Henson and John Stringfellow

Present -The Aerial Steam Carriage

Good Morning Steward, is this the boarding area for the flight across the Channel?

Yes ma’am. Check your luggage at the gate and proceed up the boarding ramp.

My daughter and I are so excited! It is safe to fly, isn’t it?

Absolutely, ma’am. These airplanes incorporate all the latest safety features: high-pressure steam engines, double-walled boilers and the finest canvas propellers. After all, this is 1848.

This imaginary conversation would have occurred if Henson and Stringfellow had been successful with their “Aerial Steam Carriage,” but luck was not on their side. William Samuel Henson was an engineer and inventor who was familiar with the aeronautical work of George Cayley. Discussions with his associate John Stringfellow led to his design for a large passenger-carrying steam-powered monoplane, with a wing span of 150 feet, named “ARIEL – The Henson Aerial Steam Carriage,” for which he received a patent in 1842. Henson, Stringfellow and two others, Frederick Marriott and D. E. Colombine, incorporated the Aerial Transit Company in 1843, and fully intended to construct the flying machine.

Henson had demonstrated a model of his design, which may or may not have made at least one tentative steam powered flight as it lifted, somewhat, off a wire guide. Numerous attempts to actually fly the large model (and an even larger model with a 20 foot wing span) were made between 1844 and 1847, but none of the attempts were successful.

Now, let’s travel back to the very beginning and try to put the pieces together………………………………

In the small English town of Chard, evidence of the burgeoning industrial revolution could be heard every day in the chattering machinery of the lace mills during the 1840s. Festooned with endless racks of brass bobbins and intricate levers, these mechanical marvels produced all kinds of goods, from curtains and ornamental lace for ladies to mosquito nets for hardy explorers. Automatic looms wove the threads, commanded by a system of computer like punch cards. John Stringfellow, master lacemaker and skilled mechanic, knew how every swinging bar and meshing gear worked in these great machines. After all, he had designed them.

A man of his age, Stringfellow found himself drawn to the new advances in science. With his trousers hiked up, he waded through the shallow waters of the Chard canals, chipping fossils from their chalky banks to help him investigate the ancient past. In a makeshift laboratory behind his home, he produced flickering sparks using the new science of electricity. And he was fascinated by the steam engines that powered his mills and were transforming his world.

William Henson, also a lacemaker, knew Stringfellow through family connections. Henson was captivated by the new methods of travel then being introduced, including steamboats, railroads and the first road carriages. He also marveled at the hot-air balloons that floated majestically over the countryside.

Exactly how these two inquisitive men joined forces to design an airplane is not known. We do know that both frequented the Chard Institute, a lecture hall where the intellectually curious came to witness demonstrations on scientific topics. There is a story that Stringfellow was fond of tossing sheets of cardboard’ (possibly model airfoils) across the empty gallery between lectures. Perhaps that’s how their partnership began.

By 1840, the men were working together on a study of bird flight. Using Stringfellow’s taxidermy models, they measured the wingspans of different species. Through spyglasses, they also observed birds flying across the countryside.

Soon they reached a momentous conclusion. While flapping wings was fine for the birds, they decided that a flying machine should have stationary wings, set at a slight angle to the wind and propelled through the air at great speed, just like Stringfellow’s cardboard sheets at Chard Hall. What they needed was a dependable way to experiment with this new idea. In the summer of 1841, Stringfellow boarded the Great Western Railway, bound for London, intent on doing some research along the way. Imagine their surprise when his fellow passengers spied wings of different shapes and sizes floating just outside their car windows. The inventor had somehow secured the conductor’s permission to perform tests during the journey (we might think of them as wind tunnel tests).

Both men agreed that steam was the means to propel their airfoil. The steam engines of their day were ponderous affairs, however, with great cast-iron cylinders weighing hundreds of pounds for each horsepower produced. But Stringfellow had already begun designing miniature engines, jewel-like machines with tiny, soldered fittings. He fired their conical boilers with methylated spirits, burned in thimble-size reservoirs. One of his masterpieces was so light that he could even send it through the mail. Coupling those advances with the new Ericsson screw-type propeller, Henson and Stringfellow created a now-classic aeronautical design: the fixed-wing, propeller-driven airplane.

Certain they were on the right track, the team began drawing up plans for a full-size flying machine. Dubbed Ariel, the craft they envisioned would be colossal. A fixed wing spanning 150 feet would provide 4,500 square feet of sustaining surface. A streamlined cabin, fitted with glass windows, would accommodate passengers and crew. Specially designed high-pressure steam engines would operate twin six-bladed propellers to create the necessary thrust. A pilot-operated tail and rudder system would guide the great craft, while vertical stabilizers would steady the machine. A tricycle landing gear fitted with shock-absorbing wheels would facilitate takeoffs and landings.

With each pound of weight supported by two square feet of wing surface, Ariel would hopefully reach a cruising speed of about 50 mph. To achieve takeoff, the inventors planned to accelerate the machine down a launching ramp, with the wing fabric reefed back to reduce drag. Once perfected, the craft was to carry sufficient coal and supplies to complete a 500-mile flight.

Surprisingly modern features were incorporated in the design. The wing would gain its strength from hollow laminated spars that supported 26 gracefully curved ribs. Using the latest technology from bridge-building, the inventors would employ pylons, strategically placed across the span, to carry wire trussing out to the wings. The inventors also devised oval-section bracing wire to reduce drag during flight.

The wings of the airship would be delicately cambered and double-surfaced for maximum lift. Their long span and narrow chord would make them among the first high-aspect-ratio wing designs in history. Both wings and fuselage were to be covered with oiled silk, to provide a sealed skin for landing on water.

In more than a thousand experiments, using whirling arms and other apparatus, the inventors correctly identified the center of pressure and other key features of aircraft design. It is believed that they also secured the services of a mathematician who performed calculations using differential calculus to verify that each piece of the craft was as light and strong as possible.

Such complex innovations might seem impossible for a pair of Victorian inventors. But a set of moldering engineering drawings, purchased at auction in 1959, proves that the story is true. Meticulously prepared plan views and isometric drawings depict an exquisitely detailed, surprisingly modern-looking aircraft. And in the records of the British Patent Office there exists a complete patent application for ‘a locomotive apparatus for flying through the air,’ submitted by William S. Henson and John Stringfellow. Their patent was granted on September 29, 1842.

(John Stringfellow)

Now that we know the history let’s talk about the marketing……………………

The public would soon learn about Henson and Stringfellow’s plans in a big way. Frederick Marriot, a newspaperman and publicity agent, joined the team. In a spirit that seems to foreshadow modern marketing tactics, the flamboyant Marriot unveiled a full-blown public relations campaign.

One can only imagine the public’s reaction when, flanked by their confident promoter, Henson and Stringfellow announced the formation of the Aerial Transport Company–in effect, the world’s first airline. Subscriptions were sought to raise funds to finance the construction of the fleet’s first airship. ‘An invention has recently been discovered,’ announced a glowing prospectus, ‘which if ultimately successful, will be without parallel even in our present age.’ Readers were informed, ‘In furtherance of this project, it is proposed to raise an immediate sum of 2,000 pounds, in 20-pound sums of 100 pounds. Applications can be made to D.E. Columbine, Esquire, Regent Street.’ It’s unclear just how much was raised, but a sheaf of papers discovered among the effects of a businessman who died in 1854, included some 45 pages of reports ‘prepared for the financial backers to Ariel Project.’

To raise additional funds for the project, Marriot hit on the enterprising idea of selling promotional lithographs showing Ariel in flight. Within months, images of a great flying machine soaring over the capitals of the world were decorating homes and businesses all over Europe and America.

Now, back to the final pieces of our story………………………………………………..

On March 24, 1842, J.A. Roebuck, a member of Parliament for Bath, moved in the House of Commons for ‘the incorporation of the Aerial Transport Company, to convey passengers, goods, and mail through the air.’ Within a week, the widely read Mechanics Magazine published the full specification from the patent.

The English press was quick to offer its views. Sharp-tongued critics reminded their readers that no flight attempts had succeded thus far. More scientifically minded writers speculated about the Aerial Steam Carriage’s stability in stormy weather. Technical journals agreed or took issue with the inventors’ calculations for necessary power and their provisions for control. Debated by gentlemen in their clubs as well as workingmen in the pubs, air travel had become a topic of the day.

According to Marriot, the Aerial Steam Carriage would not only achieve the dream of human flight but also commence regular service from London to outlying cities. Special ‘aerial stations’ would be erected at each destination, equipped with smooth landing fields. Station houses, patterned after railway depots, would serve the passengers, while coaling stations, machine shops and other mechanical facilities would maintain the aircraft. Legions of workers, from boilermakers to stokers to porters, would service the aircraft and its passengers.

In times of war, Marriot argued, it might also be used in an air force. Fleets of Aerial Steam Carriages, strengthened to carry the added weight of munitions and armor, could assist the British empire in moving troops around the globe.

The firm’s grandiose plan unleashed a whirlwind of controversy and speculation. While some admired its foresight and boldness, others dismissed the idea as hucksterism. Some journalists offered mocking praise, pointing out that shipwrights and wagon makers would go bankrupt once everyone began traveling by air. Satirical cartoonists had a field day, depicting Ariel on improbable flights to places like China, with the passengers becoming embroiled in ludicrous adventures.

The Aerial Transit Company never built the large version of the Aerial Steam Carriage, perhaps because of the disappointing experiments with the model craft and, perhaps, because of the expense involved. Henson, Stringfellow, Marriott and Colombine parted company.

In 1848 William Henson and his wife, Sarah, left their native England and moved to the U.S., settling in Newark, New Jersey, where he spent the last 40 years of his life. Henson had apparently ceased his aerial research for good, and never again took up the matter. Henson, along with his wife and children, and other members of their family are buried in Orange, New Jersey.

Stringfellow remained convinced that human flight might still be within his grasp. He returned to his workshop with plans for a small aircraft, which he hoped might carry a single pilot, but age and circumstances conspired against John Stringfellow who was a man who that had been born too early to realize his dreams. He died in 1883, more than 40 years after beginning his quest, but still many years short of the day when air travel would become a reality.

I hope everyone has a good weekend and you have time to contemplate your past, and future, plans for happiness. Remember – “Gatekeeper” – and remember that aviation is suppose to be fun regardless of the airplane you fly.

Robert Novell

May 20 2022