The Golden Years and Technology – Part One – The Boeing 247 Airliner – July 14, 2023

The Snecma C.450-01 Coléoptère….A Truly Strange Craft – July 7, 2023

July 7, 2023

The Golden Years and Technology – Part Two – The Douglas Airliners – July 21, 2023

July 21, 2023

RN3DB

July 14, 2023

Good Morning,

This week I want to begin a series called “Golden Years and Technology”. This article, which is a four part series, is a reprint from a few years ago and it is well worth another look by all of us. This article is important to me, because it details how a few specific models made commercial aviation, as we know it, possible. As always, I would like all aviators to connect with their roots and one of the ways they can do that is by using the “Third Dimension Blog” as a resource.

Quote of the Week

“The desire to fly is an idea handed down to us by our ancestors who, in their grueling travels across trackless lands in prehistoric times, looked enviously on the birds soaring freely through space, at full speed, above all obstacles, on the infinite highway of the air”

Wilbur Wright – circa 1925

The Boeing 247 Airliner

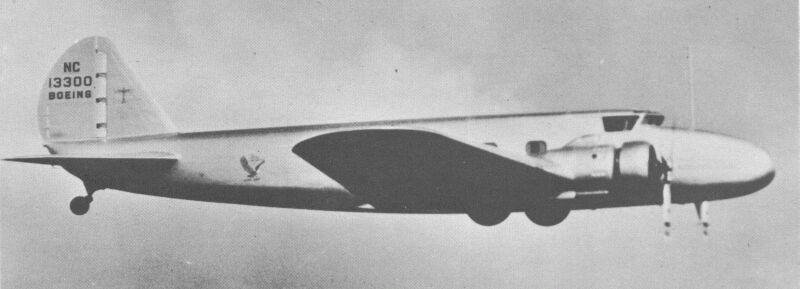

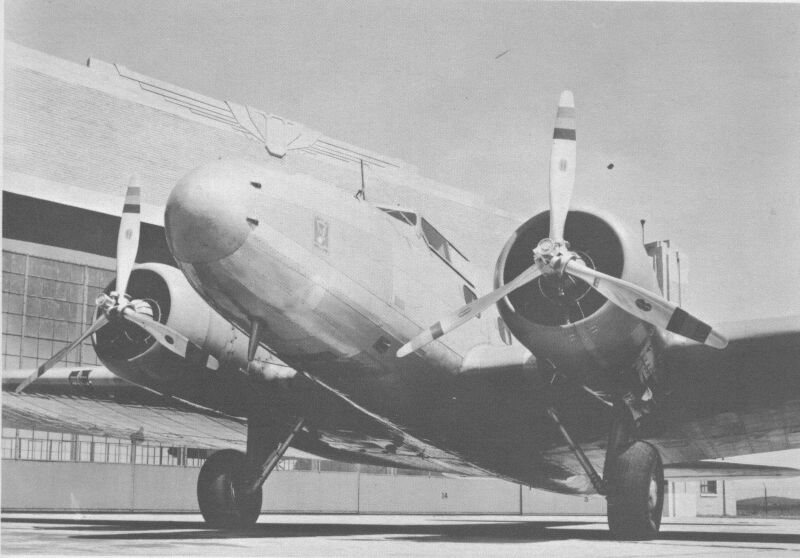

In 1930, the traveling public was more likely to take the train for long journeys than fly. The current airliners were uncomfortable, noisy, and not much faster than the new streamliner trains. Boeing, as part of the United Aircraft and Transport Company, decided to develop a new airliner based on its previous single-engine Monomail. The result was the Model 247, which carried 10 passengers at 155 mph in a new level of comfort. A revolutionary aircraft, the Boeing 247 has since become regarded as a prototype for the modern airliner because it was a clean cantilever low-wing monoplane of all-metal construction with twin-engine power plant, retractable landing gear, and accommodation for a pilot, copilot, stewardess and 10 passengers. With one engine inoperative, it could climb and maintain altitude with a full load, and the new Boeing also introduced a new feature for a civil transport aircraft— pneumatic de-icing boots.

Company conflict accompanied the development of this aircraft. Boeing’s chief engineer had called for a plane no larger than the planes in current production, claiming that pilots liked smaller planes and a larger plane would create problems such as the need for larger hangars. Fred Rentschler of Pratt & Whitney Engine Company, a member of the UATC, as well as Igor Sikorsky, who had been building large planes for years and also a member of UATC, favored a larger plane and claimed that it would offer more comfort to their passengers on long flights. Those in favor of the smaller plane won, and performance prevailed over comfort.

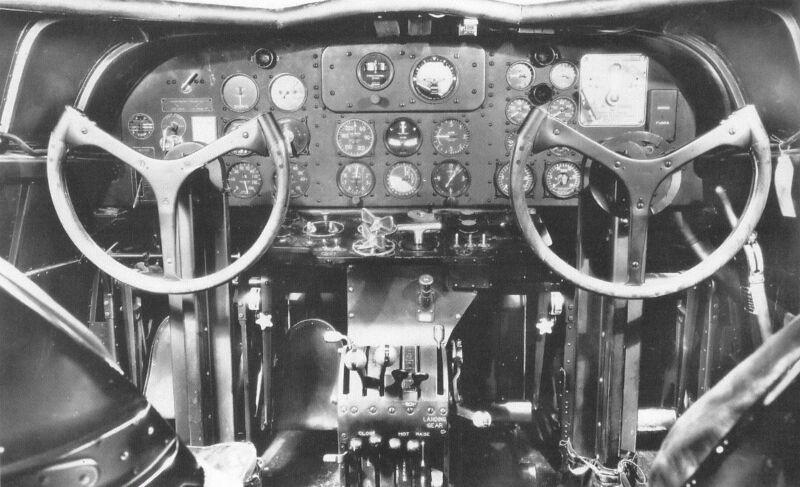

Disagreements also ensued over whether to have a co-pilot, which would increase passenger safety and comfort but would also add to the weight. The co-pilot was added. The propeller was also a source of controversy. Frank Caldwell’s two-position variable-pitch propeller had already been perfected in 1932. But Boeing argued that the device weighed too much, and decided to use a fixed-pitch propeller. Nevertheless, with some foresight, the plane was designed so that there would be sufficient propeller clearance if a variable-pitch propeller was added later. This turned out to be a smart decision, since the 247D switched to the newer propeller.

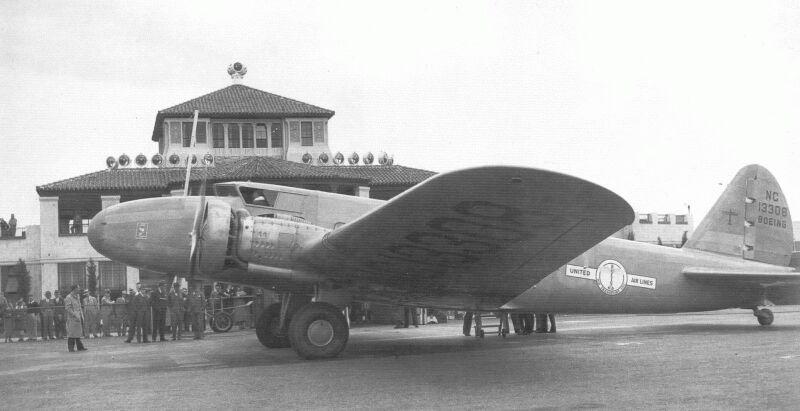

The twin-engine Boeing 247 made the three-engine airplane obsolete and gave the U.S. airline industry an enormous boost. United Airlines, a member of the holding company United Airlines and Technology Corporation (UATC), purchased 60 of the planes and soon outdistanced all of its competitors.

It appeared that the Model 247 had a bright future in airline service but the large order took up all of Boeing’s manufacturing capacity and sent other airlines searching for alternatives. TWA went to Douglas and the DC-2—the DC-2 had a greater seating capacity and a higher speed— and soon most US airlines were ordering DC-2’s.

United Airlines had great success with its sixty planes for the relatively short time that it flew them, and many of United’s aircraft were later purchased by Western Airlines.

Next week we will continue this series by highlighting the DC-1/2/3. Until then, take some time to look back, connect with your past and remember as an aviator you are a “Gatekeeper of the Third Dimension”.

Protect your profession, your future, and the future of your fellow aviators.

Robert Novell

July 14, 2023

P.S. The rest of this page has a few pictures of the Boeing 247. These were borrowed from Holcomb’s Aerodrome located at www.airminded.net. Great website for all of us aviation enthusiast—take a look!

| Specifications: | Boeing Model 247D |

|---|---|

| Wing span: | 74 ft (22.6 m) |

| Length: | 51 ft 7 in (15.7 m) |

| Height: | 12 ft 6 in (3.8 m) |

| Wing Area: | 836.44 sq ft (77.70 sq m) |

| Empty Weight: | 8,940 lb (4,055 kg) |

| Gross T/O Weight: | 13,650 lb (6,192 kg) |

| Maximum Speed: | 200 mph (322 km/h) |

| Service Ceiling: | 25,400 ft (7,740 m) |

| Rate of Climb: | 1,150 ft (350m)/min |

| Normal Range: | 800 miles (1,297 km) |

| Engines: | Two Pratt & Whitney Wasp S1H1-G, 550 hp, 9-cylinder radial engines. |