The Plane and the Iron Horse — Part Three — July 29, 2011

The Plane and the Iron Horse — Part Two — July 22, 2011

July 22, 2011Main Line Carriers, Regional Carriers, Unions, and the Battle Lines are Drawn – August 12, 2011

August 12, 2011The Plane and the Iron Horse

Part Three

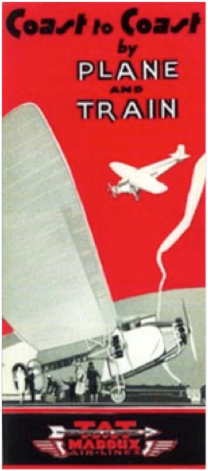

There was a time when coast to coast travel was not a five hour event in the life of a traveler but instead was accomplished by train over a period of days— but then someone decided that maybe a plane/train concept would work. This week we will finish our story.

The article presented below is by George E. Hopkins and is well written with all of the facts for the time so come with me now as we turn back the hands of time and revisit the beginning of a new era.

TRANSCONTINENTAL AIR TRANSPORT, INC.

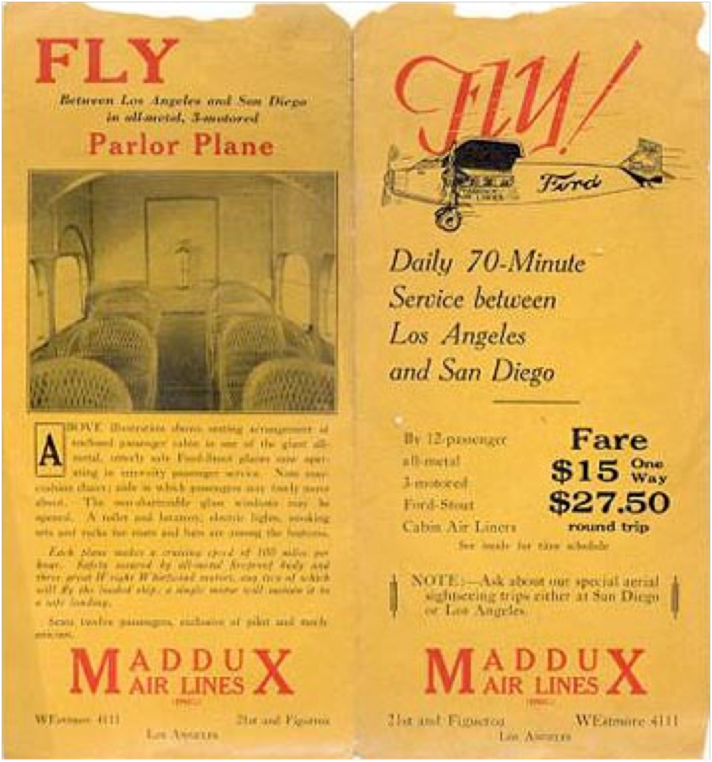

The second day aloft differed from the previous day only in that now the plane flew over western mountain ranges rather than the flat plains of the Midwest. This occasionally forced the Trimotor to altitudes in excess of 8.000 feet, engendering considerable popping in everybody’s ears. A cabin heater, however, kept the temperature at a relatively comfortable 60 degrees. After stops at Albuquerque, Winslow, and Kingman, Arizona, the big Ford finally breasted the coastal range east of Los Angeles, settling to a landing at the Los Angeles airport about 4 P.M. The transcontinental odyssey—about 1,000 miles by rail and the remaining 2,000 by air —had taken forty-eight hours.

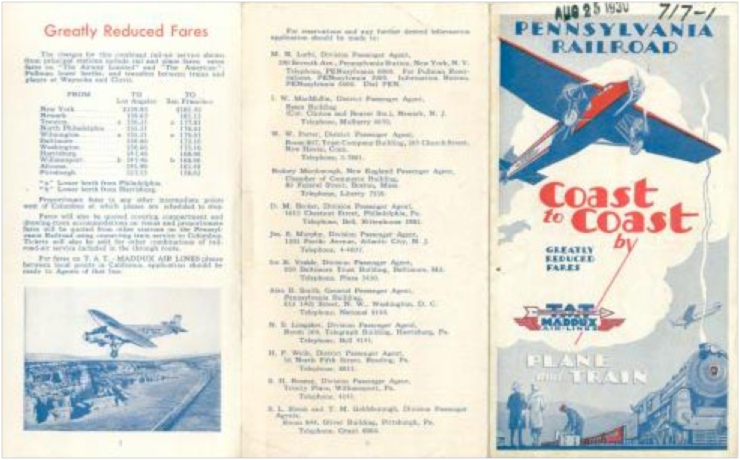

What became of this fascinating experiment in air-rail transportation? In one sense it was a casualty of the Depression. Transcontinental Air Transport catered exclusively to the “better class” of air traveler, charging 16¢ a mile for its services, or a minimum $351.94 one way with lowerberth Pullman accommodations. This fare was nearly half again as high as the most expensive railroad accommodations. In addition, TAT enhanced its snob appeal by lavishing luxury on every aspect of its operation, even going so far as to give every passenger on the full transcontinental run a solid gold fountain pen from Tiffany’s.

After the stock-market crash and a particularly nasty fatal accident in New Mexico—on September 4, 1929, when the “City of San Francisco” hit Mount Taylor during a thunderstorm, killing all eight persons aboard—the number of boardings declined precipitously. In desperation Keys took to flying his employees about to make it appear as if there were plenty of passengers. But in fact businessmen, the group TAT really focused on, suddenly found that they weren’t in nearly so much of a hurry as they had thought. Even in its best month, August of 1929, TAT lost money. Overall it lost nearly three million dollars in its short life. In October, 1930, TAT was merged with Western Air Express, which, after many corporate twists and turns, became Transcontinental & Western Air, the predecessor of TWA.

The inability of TAT to turn a profit convinced Postmaster General Brown that he would have to bludgeon the air-mail contractors into undertaking passenger operations. Most of the contractors shook their heads sagely and vowed to stick with open-cockpit mail planes. Far better, they thought, to placate Brown by offering rudimentary passenger services (mostly unadvertised), in cramped, noisy single-engine planes, than to get into the risky business of competing with the railroads. But Brown had other ideas, and in May of 1930 he called a conference of all air-mail contractors (TAT, one must remember, had no mail contract) during which he engineered shotgun weddings of several lines, offering as inducement long-term contracts. In addition, he consistently rigged the bidding process to favor the larger aeronautical concerns, which alone could afford the multiengine aircraft that made passenger operations feasible.

Brown was operating in a completely legal, though somewhat devious, manner; but his critics—mostly-smaller aeronautical operators who lacked the financial capacity to buy large airliners—labeled the meetings “Spoils Conferences,” charging fraud and collusion. Democratic politicians began to listen to their complaints after 1932, in almost direct proportion to the amount they contributed to party coffers, and such men as Tom Braniff, an unsuccessful bidder who owned an airline in the Southwest, were known to be generous and on good terms with President Roosevelt himself. Accordingly, Senator Hugo L. Black of Alabama held a sensational series of hearings in 1933-34 during which the testimony tended to support Brown’s critics. The Black Committee’s report prompted Roosevelt to cancel the contracts Brown had awarded, and his decision to allow the Army to fly the mail brought forth the first great barrage of criticism from the business community alleging that the New Deal was “socialistic.” This criticism, in which Lindbergh, Eddie Rickenbacker, Amelia Earhart, and other aviation personalities joined, was the New Deal’s first public-relations setback, but it was the Army’s sorry performance in flying the mail, rather than aviators’ taunts, that persuaded the President to return the mail service to private contractors. A few new airlines got in under the wire to join the old (reorganized) contractors in qualifying for subsidies under the Air Mail Act of 1934. but in essence the entire process tended to vindicate the much maligned Walter Kolger Brown. A viable national air-passenger service required the hidden subsidy, and the fine hand of government control was necessary. Once these facts were established, the future success of the nation’s major airlines was assured.

But all this came too late for TAT— “The Lindbergh Line.” In reality TAT represented a dream for which the technology of the day was inadequate. The transcontinental trip was fast, but it wasn’t that fast. It only beat the train by twenty-four hours, and the train was reliable—a businessman could make an appointment and keep it. With TAT he might be able to keep an appointment one day sooner.

Still, for all its drawbacks, TAT was a pioneering success in aviation history. It set new standards for safety and comfort, and, above all, its association with Lindbergh generated an enormous amount of enthusiasm for commercial passenger service. This enthusiasm began to pay off soon— but not in time to save TAT.

Many years later most of its crumbling air-rail stations still stood, mute and futile monuments to an idea whose time had not yet come. And today, nearly a half century later, in Waynoka, Oklahoma, all but the oldest residents seem puzzled at the mention of the name of Transcontinental Air Transport.

(http://cprr.org/Museum/Ephemera/PRR_TAT_1929.html)

Next week I have some commentary on the state of affairs at the airlines/unions and then I will begin a series on Delta Airlines. Take care, fly safe, and remember that all aviators are “Gatekeepers of the Third Dimension” and each of us must protect our profession and those who follow in our footsteps.

Robert Novell,

July 29, 2011