Transocean Airways – A Look Back – May 10, 2013

Was The Forerunner of The Osprey A Better Design? – May 6, 2013

May 5, 2013Aviation Wisdom From The Past – May 27, 2013

May 27, 2013“Robert Novell’s Third Dimension Blog”

Good Morning and welcome back—This week we are looking back at one of the largest non-scheduled airlines in history. This was a seven part series I published on the blog in 2011, but this time I will divide the articles up over two weeks. I hope you enjoy reading this as much as I enjoyed doing the research and bringing you the results.

A great airline…a great company. Enjoy………………………

TRANSOCEAN AIR LINES

Part One

Captain Orvis Marcus Nelson, later to become the founder of Transocean Air Lines, was a veteran pilot flying for United Air Lines when the United States entered World War II in 1941. He had then been assigned to fly for The Air Transport Command (ATC) of the U.S. Army Air Corps under a contract held by United and was one of the civilians flying the C-54 four-engine transports in conjunction with “The Purple Mission.” This was the code name for the landing, set for November 1, 1945, of the first wave of occupation troops. Okinawa, the island nearest to the Land of the Rising Sun, had been designated as the staging area for “The Purple Mission.” Servicemen, supplies, and what seemed to be every C-54 transport in the world had been amassed on the island in preparation for the invasion of Japan before the atom bomb ended the need for a land invasion.

Nelson was in flight between Guam and Kwajalein when the first atom bomb was unleashed over Japan and between Kwajalein and Johnston Island when the news of the bomb was broadcast. By the time he arrived at Honolulu there were indications that Japan might surrender, and he was directed to return his aircraft to Okinawa. Grounded on Okinawa in mid-August, Nelson and several other United crewmen sat around talking, killing time while waiting for back-to-back typhoons to wear themselves out. In the group were Sid Nelson, who had been active in the Air Line Pilots’ Association with Orvis and who would become a director of TAL; Harry Huking, a senior United pilot; and radio operator Sherwood Nichols, destined to be secretary-treasurer and one of the original directors of the airline. In the light of a single candle, with torrential rain and wind battering the canvas Army tent they occupied near the Yontan Airstrip, the conversation quickly turned to the usual topic-what to do after the war ended. Most of the men had had a taste of flying to exotic places in all the corners of the world, and they did not want to let go of that thrill. If at all possible, they wanted to continue flying for commercial airlines. Nelson reasoned that it would undoubtedly be a long time before the Japanese would be permitted to have their own domestic airline and he suggested that someone from the group propose to United Air Lines to either extend its routes across the Pacific to the Orient or organize a domestic airline in Japan. If either idea proved unacceptable to United management, Nelson felt that the next step should be to try to set up a Japanese airline themselves. The men agreed with the plan and decided there in the tent to form an association. Each member agreed to put up money if and when the time came to do so. The name they chose was ONAT for Orvis Nelson Air Transport Company, and they elected Nelson their representative to contact United. United’s “Pat” Patterson rejected the proposal to extend its service to Hawaii or to establish a domestic airline in Japan. However, he did help Nelson by providing him with a letter of introduction to General Douglas MacArthur, the Allied Supreme Commander in charge of the reconstruction of Japan and from whom permission for the venture would be required. Nelson then went to an old friend, Colonel W.E. “Dusty” Rhoades, who had been MacArthur’s personal pilot throughout the war, and asked him to explore the project with the general in Tokyo. The answer was again discouraging. MacArthur rejected the proposal, saying he thought it inadvisable to set up an American carrier in Japan until a formal peace treaty was signed. Disappointed by his failure to interest either United or MacArthur in their plans, Nelson shelved the Okinawa group’s idea.

By early March, Nelson was back flying United’s Denver-to-San Francisco route when he received a call from Jack Herlihy, vice-president in charge of operations for UAL. Herlihy asked Nelson how soon he could organize a flying operation in the Pacific for the ATC under a subcontract from United to provide twice-daily transport service between Hamilton Field near San Francisco, and Hickam Field, Hawaii. Nelson jumped at the opportunity without concern for “how soon.” He knew he could do it. Herlihy offered to lend key personnel to begin the organization and told Nelson that negotiations were already under way for the lease of twelve surplus U.S. Air Force C-54s. Then he issued a nearly impossible demand: position the first airplane in Honolulu in time for a return flight to the West Coast on March 18. This meant that Nelson, a pilot without an airplane or a hangar to put it in, had just ten days to construct an airline. Nelson began moving at top speed within seconds after his conversation with Herlihy.

He first called his wartime radio operator, Sherwood Nichols, who was then working as a station attendant for United at Boise, Idaho. Nichols immediately agreed to join Nelson as chief of communications. The next items on Nelson’s agenda were to locate the rest of the Okinawa group, borrow the United men Herlihy had promised, place classified ads for flight crews in the San Francisco and Los Angeles newspapers, and then telephone Hamilton Field to inform them he was in business. To his surprise, this news had already reached the installation earlier in the day. Base personnel told Nelson that some fifty demobilized pilots were already on their way to apply for jobs. Several thousand telephone calls for Nelson were received at his San Lorenzo, California, home during the first twenty-four hours of his search for flight crews, setting a record at the local telephone company for the most calls ever routed to a residence.

Source Document (Article and Photos)

TRANSOCEAN AIR LINES

Part Two

On March 11, 1946, Nelson terminated his employment with United Air Lines and then attended a conference sponsored by the ATC staff for United Air Lines and the other subcontractors on the transpacific project. General Bob Nowland presided over the discussion. Nowland, who was then the commanding general of the Pacific Wing of the ATC, had been a first lieutenant in Nelson’s Army Air Corps outfit in the Philippines in 1928 and 1929. Colonel Ray T. Elsmore, another prominent officer at the conference, had once been employed by Western Air Lines, had practiced law, and had been a pilot for the U.S. Postal Service. Elsmore had served as Director of Air Transport, Allied Air Forces in the Southwest Pacific, under General George C. Kenney during World War 11. On active duty since 1940, Elsmore had been in the Philippines when the Japanese invaded the islands but had managed to escape to Australia on the last airplane out. He subsequently directed troop-carrier ATC operations in the Pacific.

Nelson was impressed with Elsmore’s demeanor and military and commercial flying record and hired him on the spot as his chief assistant. Elsmore soon would carry the title of executive vice president of ONAT. When Nelson returned to his San Lorenzo home that night, he was greeted by a large group of pilots, copilots, radio operators, navigators, flight engineers, and operations men filling his front porch and milling around in front of his house. Most were hired that night, including William Word, who would become a flight captain for ONAT, and Harvey Rogers, later to be chief pilot of the airline.

The hiring of Sam Wilson, Wally Simpton, and Art Bisset was typical of the flamboyant way Nelson gathered his personnel. Wilson was still in the Air Corps but had decided to make the switch to civilian life when he heard of Nelson’s “start-up” airline in March, 1946. He called the local United Air Lines office for information and waited while someone there telephoned Nelson’s home. When Nelson answered, Wilson got on the line: “I hear you’re looking for pilots,” said Wilson. “Yes,” replied Nelson. “You are looking for a job?” Maybe,” said Wilson cautiously. “O. K. – you’re hired.” This seemed a little abrupt to Wilson. “Don’t you even want to see my logbook?” he asked. “Hell, no – I’ve heard all about you.” “Well … say, Nelson, there’s another fellow here who’s looking for a pilot’s job-name of Wally Simpton.” “Is he O.K.?” asked Nelson. “Yes. . . “O. K.-he’s hired.”

Bisset had just been discharged from the military when he spotted the “Flight Engineers Wanted” advertisement in a local newspaper and went to Oakland Municipal Airport (now Oakland International Airport) to check it out. When Nelson asked what kinds of airplanes he’d flown, Bisset started to reply with B-17s and B-24s when Nelson interrupted to tell him he was hired. The frenetic pace picked up. On Wednesday, March 13, Nelson and Captain W. W. “Pop” Warner headed for the San Francisco International Airport to receive the first of the twelve Army owned C-54s to be leased to GNAT and ferry it across San Francisco Bay to Oakland. No sooner had they taxied the aircraft to a stop when Nelson hurried off to find office space for the operation. He discovered that the old two-story stucco hotel at Oakland Municipal Airport (said to be the first airport hotel in the nation) was vacant and signed a lease with the Port of Oakland.

Oakland Municipal Airport had been the departure point for many of the early air races such as the Dole Pineapple Race on August 16, 1927. That year eight fliers competed for $35,000 in prize money offered by Jim Dole, so-called “Pineapple King” of Hawaii. The Oakland Airport was also aviatrix Amelia Earhart’s departure point on May 20, 1937 when she and her navigator, Paul Noonan, began their second attempt to circle the globe. The Lockheed lifted off from Runway 27 heading east. They hop scotched across the country, landing at Tucson, New Orleans, and Miami. On June 1 they left Miami, stopping en route at such places as Caripito, Venezuela; Natal, Brazil; Fort Lamy, Chad, French Equatorial Africa; Calcutta, India; and Singapore. They were more than half way around the world when they landed at Lae, New Guinea, on June 30. On July second, after departing Lae, Amelia Earhart’s plane vanished over the Pacific without even an oil slick. A new era at the historic Oakland Airport was about to begin as Orvis Nelson Air Transport went into business. Soon veterans from all branches of’ the armed forces were queued in a long line stretching from the entrance, down the steps and to the tiny airport restaurant up the street. They looked as though they had just been discharged as most were still dressed in their military uniforms and carrying duffel bags.

Nelson’s “executive office” was bare except for a single telephone positioned in the middle of the floor. Between phone calls Nelson asked few questions of the men who came through his door to be interviewed and hired nearly every one of them. Within several days Nelson had established the dispatch office, the chief pilot’s office, and a room for communications and navigation personnel on the first floor. On the second floor he installed the payroll and accounting departments, a pilot’s lounge for the standby crew, plus offices for the secretaries, Elsmore, and himself. The place hummed with activity and excitement. Even Nelson’s former bosses at United were caught up in the enthusiasm generated by the exuberant GNAT group. Jack Herlihy not only kept his word to Nelson for the loan of certain personnel but also persuaded UAL management to supply some of the needed office equipment and furniture, applications and other business forms. But most important, he provided two office managers to assist in creating office procedures and company policies. On the eleventh day, after the ten days of “creation,” Nelson rested. In that time, Nelson had managed to create the foundation for an airline that would eventually become the world’s largest supplemental air carrier.

Source Document (Article and Photos)

TRANSOCEAN AIR LINES

Part Three

On the morning of March 16, 1946, the first flight departed for Honolulu in one of the leased C-54s. The ATC wanted the airplane to be in position in Honolulu to ferry to the U.S. mainland a load of military personnel returning from the South Pacific theaters of war on March 18, which was Nelson’s thirty-ninth birthday. This was the inaugural flight of the ATC contract calling for two round trips daily between Hamilton Field, California, and Hickam Field, Hawaii. At the controls was Captain Jerry Byrd, a former Navy pilot. In the right seat was Jack Brissey, who had been one of the Air Corps’ famous “Wilmington Warriors,” the ferrying group for domestic and transatlantic flights during the war. Art Bisset, former Air Corps flight engineer, who had trained pilots in B-17s ‘and B-24s during World War II, was the flight engineer. Bisset’s meticulous attention to detail would later earn him the position of chief inspector for the airline. Ralph Lewis, violinist in the Lawrence Welk Orchestra before the war and a former radio broadcaster, was the radio operator. Al Mays, ONAT’s first chief navigator, a soft-spoken southerner with a penchant for being precise in his calculations, was tabbed for that first flight. Ten days after the historic first flight of ONAT, Nelson flew to New Jersey to marry Edith Frohboese, a petite blonde United Air Lines stewardess. Less than two hours after the wedding ceremony, the newlyweds were headed for California on a cross-country honeymoon by train.

Esther Lavagnim, an attractive, dark haired, twenty-two year old girl, was the first secretary of the airline. Esther came for her job interview dressed in an eye-catching black and white checked suit, high heels, and a wide brimmed black hat. She was greeted by a chorus of whistles and appreciative comments by the young aviators waiting outside the door. Before many days had passed, Patricia Olesten and Vivian Sims were hired. Patricia’s job was to type statistical reports; Vivian was to be Nelson’s private secretary for many years.

Others of the original GNAT office personnel and ground crew were William R. Rivers, Douglass F. Johnson, John Markusen, Jack Ullner, Louis Lombard, Don Sheets, Andrew McKelvie, and James Clarksen. This small band of employees, along with the flight crew members hired during that first month, forged the family-like bond that became the hallmark of the company through the years. Orvis Nelson had always admired the older pilots and held a certain fondness and admiration for them. Later, he would add such men as E.L. Sloniger, Colonel Benton “Lucky” Baldwin, and Chuck Sisto to the airline’s roster.

Transocean is born…

ONAT was profitable from the start. In Just two months the company netted nearly $70,000. But because income tax rates for individuals were high and as Nelson had no extraordinary expenses to write off, he decided to incorporate. A contest was held to name the new corporation. Ray Foster, a dispatcher at the headquarters, submitted the winning name. ONAT became Transocean Air Lines on June 1, 1946.

Nelson immediately sold $200,000 worth of stock and gave one percent to each department head and to the loyal members of the Okinawa group. His only personal outlay of cash was $1,000 down payment for a $25,000 insurance policy for his employees. During the first months of operation, maintenance work was subcontracted to the Air Transport Division of the Matson Navigation Company at Oakland Airport. But with the quick growth of Transocean, the corporation was able to secure quarters in a large hangar vacated by MATS and took over its own maintenance by the end of July. Nelson had a clear concept of what was required of an airline to succeed in the post-war years: a carrier capable of supplementing and assisting the scheduled airlines; one with a high load factor, maximum utility and no frills; plus a system to secure return loads when needed in order to keep rates generally lower than other carriers. With this vision, Nelson and his team decided to enter the commercial contract field with company owned aircraft. At the end of World War II, military surplus airplanes were available for purchase by veterans from the War Assets Administration of the U.S. government at a fraction of their real worth. Veterans Ray T. Elsmore and William L. Word, representing Transocean Air Lines, were among the first to receive their C-54s. Ownership of the four-engined transports would later be registered with the CAA in Transocean’s, name. Ted Vinson, Bill Word, and Jim McCoy flew aircraft N66635 and N66644 from Walnut Ridge, Arkansas and Albuquerque, New ‘Mexico, to a modification center in Southern California for CAA conversion from military to commercial configuration and for certification. By the time these two airplanes were purchased, Transocean was flying twelve government-leased planes on the San Francisco-Honolulu run.

With the arrival of the first two C-54s at Transocean’s headquarters in Oakland, California, TAL began its rapid ascent into sunny skies. Several years would pass before Nelson would reflect on the irony that Transocean, conceived during a raging storm, would pass through innumerable squalls in its corporate life and end by being engulfed in a predatory tidal wave.

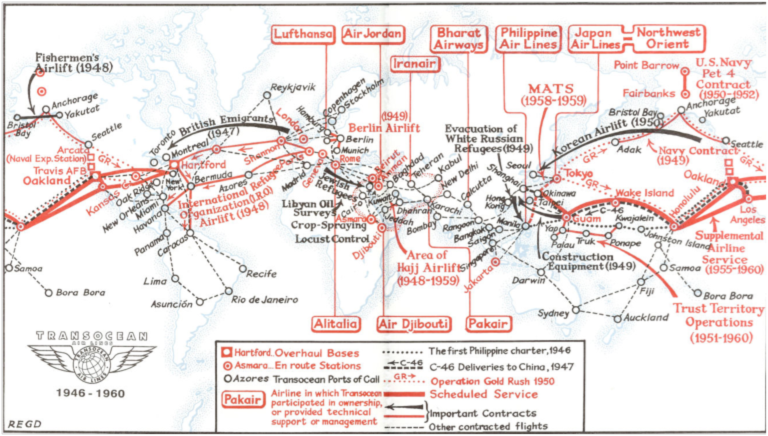

At its height, the Transocean organization included 10 companies, making it the first aviation conglomerate. The airline itself employed 2.200 persons. Including the personnel of its subsidiary companies, the total number exceeded 6,700. Transocean’s gross annual sales climbed as high as 50 million dollars and by April 1958, after 12 years of business, Transocean’s aircraft had flown a total of 1,290,966,900 passenger miles, 126,990,642 cargo ton-miles, and 66,828,237 aircraft miles – the equivalent of more than 135 round-trips to the moon!

Source Document (Article and Photos)

TRANSOCEAN AIR LINES

Part Four

Transocean’s first commercial contract was a round-trip charter between the U.S. mainland and the Philippines in June 1946, not long after the start of the ATC contract. Nelson negotiated with a Filipino newspaper publisher, a Dr. Yap, to fly to Manila a group of his countrymen who wanted to participate in the first Independence Day activities on the Fourth of July 1946. But the modification center in Van Nuys, California was unable to finish on schedule the conversion from cargo to passenger configuration of either of Transocean’s two aircraft. As a consequence, TAL lost the job. The Philippine contingent had to find its own transportation to Manila. With help from Washington, D.C., most were able to hitch rides on ATC planes.

Finally, the conversion work on one of the C-54s was completed during the first week in July and Nelson sent it to Manila to bring the Yap Group back to the states. It turned out that Colonel Andres Soriano, president of Philippine Air Lines and owner of the San Miguel Brewery, had seen the TAL DC-4 leave Manila with Dr. Yap’s passengers, and he called Nelson from Manila to find out if he would set up a transpacific charter service with him under Philippine Air Lines sponsorship. After Nelson paused briefly to contemplate the proposal, he and Soriano agreed on two trips. An extension of the contract would have to be preceded by further discussion. Colonel Soriano wanted to start the charter service immediately. This news touched off a flurry of activity at Transocean’s headquarters in Oakland. The airline’s second C-54 was still undergoing modification to DC-4 standards in Southern California. The first aircraft, now back from Manila, was still equipped with bucket seats, and there was insufficient time to install regular passenger seats.

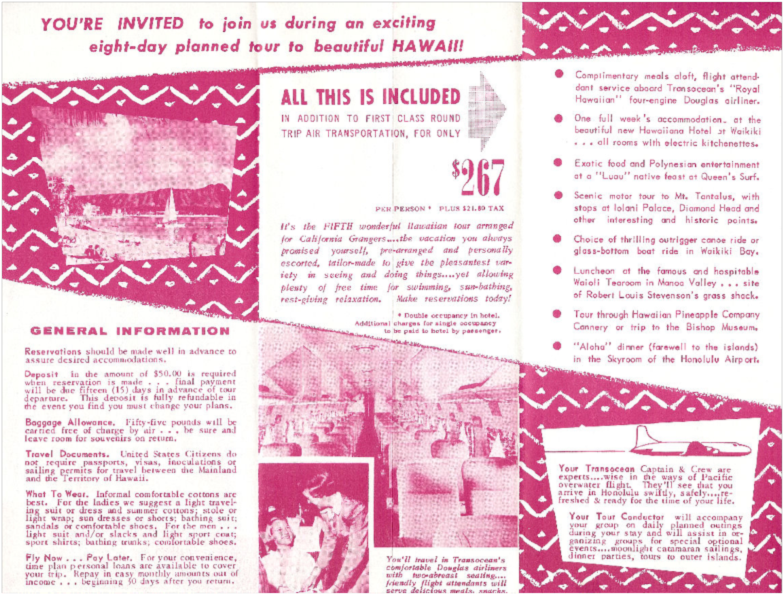

On the night of July 22, the TAL employees were in high spirits as they set out to fix up the plane for the first trip under contract to Philippine Air Lines. Bill Rivers, the airline’s new purchasing agent, spent the night on his knees padding the seats with foam rubber while Flight Engineer Jim McCoy fastened the headlining. People from administration, operations, maintenance, and several flight crew members assisted as needed. When their work was nearly completed, they put air mattresses aboard so the passengers could spread them out on the cabin floor and stretch out to sleep. Because Colonel Soriano would be meeting the flight, Nelson decided to fly the DC-4 himself. It would be a good time to cultivate their relationship and develop more business with Philippine Air Lines. His wife, Edie, accompanied him on the trip and served as stewardess. It was morning before the last of the work had been finished on the DC-4, and it was ready to fly. Nearly every employee-even their husbands, wives, and children – showed up to give an enthusiastic send-off to the DC-4, which had been named Miss Independence for the Yap charter flight, now renamed Taloa-Manila Bay to honor the new service. The load consisted of thirty-five passengers and a small quantity of freight. Transocean’s first commercial flight gave the Philippines its first post-war air link with the United States. Edith Nelson had the distinction of being the first stewardess to complete the Pacific crossing for a commercial airline as Pan American employed only male stewards at the time.

Later, after Transocean sold PAL two DC-4s in return for a considerable block of stock in the Philippine airline, PAL canceled a contract it had given Trans World Airlines for the management of PAL’s domestic runs on the islands and gave the contract to Transocean. United Air Lines lent to Transocean John Hodgson, one of their captains, who had been manager of United’s Alaskan operation during the war, to go to the Philippines and establish the domestic division of PAL. He was in Manila for a year when Nelson sent Sam Wilson to take over the operation. Eventually, Nelson, Sherwood Nichols, and Ed Ringo worked out a contract with Soriano for the establishment and operation of a Philippine Air Lines international service to the United States, the Orient, and Europe. In the months following those first flights to the Philippines, however, N66635, referred to within the airline as 635, was the most widely known and flown aircraft in the Pacific. During the late summer and fall of 1946, aircraft 635 was the only commercial channel of communications between the United States and the Orient. This was because Pan American had suspended its operations and a maritime strike put the ships at anchor. That single DC-4 played a dual role carrying the flags of both the United States and the Philippines. Adding to the mystique already surrounding Transocean were the quick-change paint jobs given 635 every time it arrived in Manila. As soon as the engines were shut down, a crew of painters would rush to paint over the TAL lettering to read “Philippine Air Lines” before departure time to the Orient. This created the impression along the route that Transocean had an entire fleet of aircraft servicing the South Pacific.

The TAL-PAL combination began service to Shanghai in September of 1946 and to Bangkok in November. On this route between Honolulu and Manila, Nelson used double crews, each crew consisting of captain, copilot, radio operator, navigator, and flight engineer. The first crew would fly the aircraft from Honolulu to Wake Island, where the second would take over en route to Guam. Then the first flight crew would again take command for the journey to Manila. After a 24 to 48 hour layover at each station, the two crews would alternate in flying the aircraft. Some flights would continue on from Manila to Shanghai, Bangkok, or Karachi. The double crew concept was a novel idea later to be used by other airlines.

Source Document (Article and Photos)

That is it for this week. Have a good weekend, keep friends and family close, and remember that those who will follow in your footsteps are depending on you. Be a “Gatekeeper.”

Robert Novell

May 10, 2013