Alaska Airlines Part Two – March 9, 2012

The Wright Brothers Flyer – March 7, 2012

March 7, 2012Flying Cargo Container – March 14, 2012

March 14, 2012“Robert Novell’s Third Dimension Blog”

http://splash.alaskasworld.com/newsroom/asnews/photos.asp

Good Morning—it is Friday and it is time to continue our series on Alaska Airlines. I hope everyone had a good week, that you enjoyed the preview on Wednesday and found the sales brochure on the Wright Flyer to be an interesting footnote on aviation history.

Today will be Part Two of the series on Alaska Air and this will finish up the series. So, let’s continue with our story and if you need to refresh your memory on Part One click here….. Alaska Air-Part One.

Enjoy……….

Alaska Airlines – Part Two of Two

http://www.fundinguniverse.com/company-histories/Alaska-Air-Group-Inc-company-History.html

When Cosgrave took over, Alaska Air was $22 million in debt to its creditors. In an effort to salvage the company, the airline cut flights and employees and dropped its freight business entirely. The new management also set out to improve the airline’s punctuality in hopes of banishing its unflattering image as “Elastic Airlines.” By 1973, the airline’s performance had improved and it was turning a small profit. In this new, less-flamboyant phase symbolized by the more sober logo of a native Alaskan that was painted on the tail of the company’s planes, the airline remained profitable throughout the mid-1970s.

With the passage of the Airline Deregulation Act of 1978, the American airline industry underwent a radical transformation. Alaska Airlines also underwent a transformation of sorts at the start of the new era. The real estate arm of the company was broken off into a separate company. Cosgrave became chairman of the new firm, relinquishing the reins of the airline to his close associate, Bruce R. Kennedy. In alliance with Alaska Air, Cosgrave then launched a failed campaign to take over one of the airline’s competitors, Wien Air Alaska, that later resulted in federal fines for Alaska Airlines and its leaders for improprieties during the attempt.

Kennedy’s role as leader of Alaska Air was to shepherd the airline through the marked expansion of the brave new unregulated world of the 1980s. Immediately, the company placed two more continental American cities on its route map: Portland, Oregon, and San Francisco, California. The Arctic cities of Nome and Kotzebue, and then Palm Springs, California, were added shortly; and Burbank and Ontario, California, came on line in 1981.

By 1985, Alaska Air was serving cities in Southern California, Idaho, and Arizona as well, and profits were up. The company was able to settle a three-month-long strike by its machinists in June, part of an overall strategy to pare labor costs to the bone and maintain peace with its unions. In November, the company introduced a popular daily air freight service from Alaska called “Gold Streak.”

Anticipating further expansion, the airline formed Alaska Air Group as a holding company in 1985. Horizon Air, a Seattle-based regional commuter airline serving the Pacific Northwest, was purchased in 1986. A year later, the company bought California-based Jet America Airlines, which was merged into Alaska Airlines after getting slammed by larger airlines on its East-West routes from Southern California to the Midwest. Despite this setback, Alaska Air pressed ahead with its expansion into the hotly contested California market.

In an effort to compensate for the seasonal imbalance in travel to Alaska, much of which takes place during the summer, the airline in 1988 inaugurated service to the Mexican resort cities of Mazatlan and Puerto Vallarta, whose high season is the winter. By 1989, the company served 30 cities in six western states outside Alaska, and 70 percent of its passengers flew south of Seattle. The airline had successfully used its base in Alaska as a springboard to profitable performance in larger markets. Alaska Air continued its emphasis on customer service as its calling card, stressing higher-quality food and more leg room on its flights than on other airlines.

In 1990, the company unveiled a strategic plan that included lease orders for 24 new Boeing 737-400 aircraft. One provision of the transaction was the company’s sale of a $60 million preferred stock position to International Lease Finance Corporation (ILFC), lessor of the airplanes. A creative feature of the stock transaction was that the conversion rights were purchased by a large group of Alaska’s management employees, who were to redeem the stock from ILFC and convert it to common stock no later than 1997. The conversion feature was structured to create an incentive for management to achieve strong stock performance through operating results. At the same time, Alaska announced a large repurchase of shares, using proceeds of the preferred stock sale, and began an employee stock purchase plan.

The airline further expanded its route map in 1991, adding the international destinations of Magadan and Khabarovsk in the Russian Far East, and Toronto, its first city served north of the American border and east of the Rockies. (Toronto was eventually dropped in July 1992) As the company notched awards for customer service and marked its 19th consecutive year of profits in a turbulent industry, Kennedy retired in May 1991 and was succeeded by Raymond J. Vecci.

Furious competition descended on Alaska Air’s home turf after the carrier declined to buy its rival MarkAir Inc. in the fall of 1991. Since it began carrying passengers in 1984, MarkAir had worked out feeder arrangements with Alaska Air that kept competition to a minimum. However, after the buyout offer was refused, it unleashed low-cost service on the Anchorage-to-Seattle market and others within Alaska, where Alaska Air earned nearly one-third of its revenues.

In 1992, Alaska Air posted its first loss–$121 million–in 20 years. Under Vecci, the carrier canceled two planned maintenance facilities and deferred a massive $2 billion aircraft purchase; it was able to increase utilization of its existing planes, however. The company cut back on unprofitable routes and even tampered with its award-winning customer service formula, economizing on in-flight meals and other amenities. Attempting to reduce costs on labor resulted in predictably tense relations with the unions. The strict fiscal regimen produced prompt results; Alaska’s losses fell to $45 million in 1993 and produced a $40 million profit in 1994. Record-setting cargo operations accounted for about eight percent of these revenues.

In 1993, competition heated up, as the legendary low-cost airline Southwest Airlines entered the Pacific Northwest market by acquiring regional carrier Morris Air. United Airlines simultaneously transferred many competing routes to its less expensive shuttles. Alaska Air was able to reduce its costs, while maintaining a level of customer service that helped make it the leading carrier out of Seattle, Portland, and Anchorage. Alaska Air billed itself as “the last great airline.” Still, analysts argued that Alaska Air was in need of deeper cuts, and the company was also plagued by union strikes by flight attendants.

In early 1995, Vecci was dismissed and replaced by John Kelly, formerly CEO of Horizon Air. Alaska and Horizon expanded West Coast routes to capitalize upon a new “open skies” agreement between the United States and Canada. Alaska Air also added a new Russian destination. Its competitor MarkAir had by then centered its jet service on Denver.

In 1996, Alaska Air conducted the first commercial passenger flight using Global Position System (GPS) navigation technology. It announced plans to become the first airline in the world to integrate GPS and Enhanced Ground Proximity Warning System (EGPWS) technology, adding a real-time, three-dimensional display of terrain. The system was scheduled to be operational in all of the carrier’s Boeing 737-400s by April 1999.

Innovation was important to the company. In 1989, Alaska Air had become the first airline to use head-up guidance systems to operate in foggy conditions. In 1995, it became the first U.S. carrier to sell tickets over the Internet. The airline installed self-service “Instant Travel Machines” that printed boarding passes and allowed customers to bypass the traditional ticket counter. The addition of an X-ray device to the unit was being tested in Anchorage in the spring of 1999, which would allow passengers to check their own baggage.

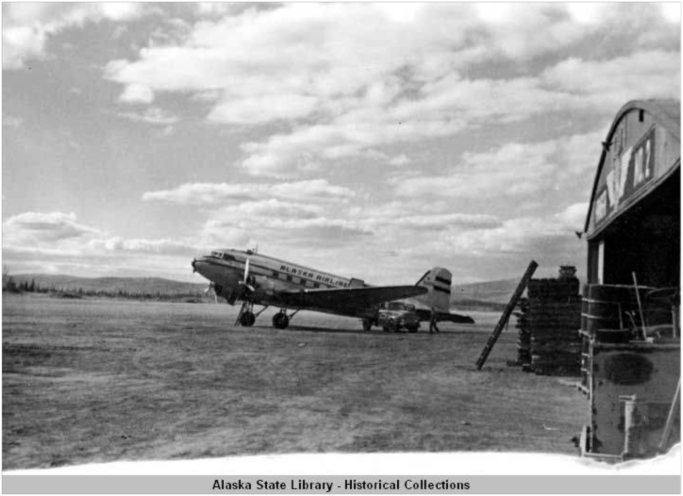

I have a few photos for you at the end of the blog you will enjoy and until next week I wish you and yours the best life has to offer.

Take Care and Fly Safe

Robert Novell

March 2, 2012

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Boeing_727-100_Alaska_Airlines_Gilliand.jpg

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Boeing_727-100_Alaska_Airlines_Gilliand.jpg