The Golden Years for Aviation and the USA – July 5, 2013

The Man Who Personifies The Independent Spirit – July 4, 2013

July 3, 2013American Airlines – History of a Great Airline – Part One – July 12, 2013

July 11, 2013“Robert Novell’s Third Dimension Blog”

Good Morning and Happy Friday. I hope everyone enjoyed their July 4th celebrations and will have a little time this weekend to take a rest, reflect back on events in aviation, and the history of our country. I have a few quotes from Thomas Jefferson and a reprint of a four part series I did in 2009 titled, “The Golden Years of Aviation.”

Enjoy…………………………

“Freedom and Liberty“

(The wisdom of Thomas Jefferson)

“I believe that banking institutions are more dangerous to our liberties than standing armies. If the American people ever allow private banks to control the issue of their currency, first by inflation, then by deflation, the banks and corporations that will grow up around will deprive the people of all property until their children wake-up homeless on the continent their fathers conquered. The issuing power should be taken from the banks and restored to the people, to whom it properly belongs.”

“The democracy will cease to exist when you take away from those who are willing to work and give to those who would not.”

“I predict future happiness for Americans if they can prevent the government from wasting the labors of the people under the pretense of taking care of them.”

“My reading of history convinces me that most bad government results from too much government.”

“The strongest reason for the people to retain the right to keep and bear arms is, as a last resort, to protect themselves against tyranny in government.”

“All tyranny needs to gain a foothold is for people of good conscience to remain silent.”

“When the people fear their government, there is tyranny; when the government fears the people, there is liberty.”

“Information is the currency of Democracy.”

A little known fact from history – Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were the last surviving members of the original American revolutionaries who had stood up to the British empire and forged a new political system in the former colonies. However, while they both believed in democracy and life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness, their opinions on how to achieve these ideals diverged over time. Both men died on July 4, 1826 in their homes and their deaths were less than five hours apart

Now let’s talk aviation……………………………..

The Golden Years and Technology

Part One – The Boeing 247 Airliner – June 05,2009

Quote of the Week

“The desire to fly is an idea handed down to us by our ancestors who, in their grueling travels across trackless lands in prehistoric times, looked enviously on the birds soaring freely through space, at full speed, above all obstacles, on the infinite highway of the air”— Wilbur Wright circa 1925

The Boeing 247 Airliner

In 1930, the traveling public was more likely to take the train for long journeys than fly. The current airliners were uncomfortable, noisy, and not much faster than the new streamliner trains. Boeing, as part of the United Aircraft and Transport Company, decided to develop a new airliner based on its previous single-engine Monomail. The result was the Model 247, which carried 10 passengers at 155 mph in a new level of comfort. A revolutionary aircraft, the Boeing 247 has since become regarded as a prototype for the modern airliner because it was a clean cantilever low-wing monoplane of all-metal construction with twin-engine power plant, retractable landing gear, and accommodation for a pilot, copilot, stewardess and 10 passengers. With one engine inoperative, it could climb and maintain altitude with a full load, and the new Boeing also introduced a new feature for a civil transport aircraft— pneumatic de-icing boots.

Company conflict accompanied the development of this aircraft. Boeing’s chief engineer had called for a plane no larger than the planes in current production, claiming that pilots liked smaller planes and a larger plane would create problems such as the need for larger hangars. Fred Rentschler of Pratt & Whitney Engine Company, a member of the UATC, as well as Igor Sikorsky, who had been building large planes for years and also a member of UATC, favored a larger plane and claimed that it would offer more comfort to their passengers on long flights. Those in favor of the smaller plane won, and performance prevailed over comfort.

Disagreements also ensued over whether to have a co-pilot, which would increase passenger safety and comfort but would also add to the weight. The co-pilot was added. The propeller was also a source of controversy. Frank Caldwell’s two-position variable-pitch propeller had already been perfected in 1932. But Boeing argued that the device weighed too much, and decided to use a fixed-pitch propeller. Nevertheless, with some foresight, the plane was designed so that there would be sufficient propeller clearance if a variable-pitch propeller was added later. This turned out to be a smart decision, since the 247D switched to the newer propeller.

The twin-engine Boeing 247 made the three-engine airplane obsolete and gave the U.S. airline industry an enormous boost. United Airlines, a member of the holding company United Airlines and Technology Corporation (UATC), purchased 60 of the planes and soon outdistanced all of its competitors.

It appeared that the Model 247 had a bright future in airline service but the large order took up all of Boeing’s manufacturing capacity and sent other airlines searching for alternatives. TWA went to Douglas and the DC-2—the DC-2 had a greater seating capacity and a higher speed— and soon most US airlines were ordering DC-2’s.

United Airlines had great success with its sixty planes for the relatively short time that it flew them, and many of United’s aircraft were later purchased by Western Airlines.

Below are a few pictures of the Boeing 247. These were borrowed from Holcomb’s Aerodrome located at www.airminded.net. Great website for all of us aviation enthusiast—take a look!

| Specifications: | Boeing Model 247D |

|---|---|

| Wing span: | 74 ft (22.6 m) |

| Length: | 51 ft 7 in (15.7 m) |

| Height: | 12 ft 6 in (3.8 m) |

| Wing Area: | 836.44 sq ft (77.70 sq m) |

| Empty Weight: | 8,940 lb (4,055 kg) |

| Gross T/O Weight: | 13,650 lb (6,192 kg) |

| Maximum Speed: | 200 mph (322 km/h) |

| Service Ceiling: | 25,400 ft (7,740 m) |

| Rate of Climb: | 1,150 ft (350m)/min |

| Normal Range: | 800 miles (1,297 km) |

| Engines: | Two Pratt & Whitney Wasp S1H1-G, 550 hp, 9-cylinder radial engines. |

The Golden Years and Technology

Part Two – The Douglas Airliners – June 12, 2009

Quote of the Week

“Flying was a very tangible freedom. In those days, it was beauty, adventure, discovery — the epitome of breaking into new worlds.”— Anne Morrow Lindberg introduction to:”Hour of Gold, Hour of Lead” 1929

The Douglas Airliners

Donald Douglas was initially reluctant to participate in the invitation from TWA to build a new airplane. He doubted there would be a market for 100 aircraft which was the number of sales necessary to cover development costs. Nevertheless, he submitted a design consisting of an all-metal, low-wing, twin-engine aircraft seating twelve passengers, a crew of two, and a flight attendant. The aircraft was insulated against noise, heated, and fully capable of both flying and performing a controlled takeoff or landing on one engine.

Only one aircraft was produced and it made its maiden flight on July 1, 1933 flown by Carl Cover. The plance was given the model name “DC-1”. During a half year of testing, it performed more than 200 test flights and demonstrated its superiority over the most used airliners at that time. In addition, a new speed record was set when the DC-1 was flown across the United States in a record time of 13 hours and 6 minutes.

TWA accepted the model with a few modifications—mainly increasing seating to 14 passengers and adding more powerful engines—and ordered twenty aircraft. The production model was called the “DC-2”.

The DC-2 was an instant hit. In its first six months of service, the DC-2 established 19 American speed and distance records. In 1934, TWA put the DC-2 on overnight flights from New York to Los Angeles, CA. and called the service The Sky Chief. The flight left New York at 4 p.m. and after stops in Chicago, Kansas City and Albuquerque, it arrived in Los Angeles at 7 a.m. For the first time the air traveler could fly from coast to coast without losing the business day.

The DC-2 was the first Douglas airliner to enter service with an airline outside the United States. In October 1934, KLM Royal Dutch Airlines entered one of its DC-2 aircraft in the London-to-Melbourne air race. It made every scheduled passenger stop on KLM’s regular 9,000 mile route—1,000 miles longer than the official race route— carried mail and even turned back once to pick up a stranded passenger. Yet the DC-2 finished in second place behind a racing plane built especially for the competition. After that, the reputation of the Donald Douglas creation was assured and it became the airplane of choice for many of the world’s largest airlines.

Early U.S. airlines like United, American, Eastern and TWA ordered over 400 of the Douglas Airliners and it is these fleets and these carriers that paved the way for our modern air travel industry in the United States, quickly replacing trains as the favored means of long-distance travel across the country.

Below are a few pictures of the DC-1/2/3. These were borrowed from Holcomb’s Aerodrome located at http://www.airminded.net. Great website for all of us aviation enthusiast—take a look.

First flight: Dec. 17, 1935

Model number: DC-3

Wingspan: 95 feet Length: 64 feet 5.5 inches Height: 16 feet 3.6 inches

Ceiling: 20,800 feet

Range: 1,495 miles

Weight: 30,000 pounds

Power plant: Two 1,200-horsepower

Wright Cyclone radial engines Speed: 192 mph

Accommodations

3 crew and 14 sleeper passengers

Three crew and 21 to 28 day passengers

Two Crew and 3,725 to 4,500 pounds freight

The Golden Years and Technology

Part Three – The Clippers of Pan Am – June 19, 2009

Quote of the Week

The Wright Brothers created the single greatest cultural force since the invention of writing. The airplane became the first World Wide Web, bringing people, languages, ideas, and values together.— Bill Gates CEO of Microsoft Corporation

The Clippers of Pan Am

The history of Pan American Airways is inextricably linked to the expansive vision and singular effort of one man – Juan Trippe. An avid flying enthusiast and pilot Trippe, only 28 years old when he founded the airline, lined up wealthy investors and powerful government officials from his personal acquaintances in the high-society of the 1920s. However, Pan Am’s first flight was an inauspicious start to its epic saga.

In 1927, facing a Post Office deadline for the commencement of mail carriage, Pan Am had no working equipment for its sole airmail contract between Key West and Havana. Fortunately for Pan Am, a pilot with his Fairchild seaplane arrived at Key West and was willing to carry the mail to Cuba for the start up operation.

Pan Am’s fortunes took a turn for the better in the fall of 1927. Through the heavy lobbying efforts of Juan Trippe, Pan Am was selected by the United States government to be its “chosen instrument” for overseas operations. Pan Am would enjoy a near monopoly on international routes. Pan Am added lines serving Mexico, Central America, the Dominican Republic and Haiti. Most of these destinations were port cities, which could be reached only by landing on water so Pan Am made good use of its “flying boats,” the Sikorsky S-38 and S-40. Flights were eventually expanded to serve much of South America.

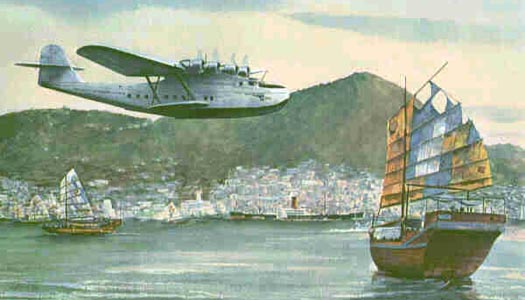

Just a few years later, Pan Am launched its effort to cross the world’s largest oceans. Survey flights across the Pacific were conducted with the Sikorsky S-42 in 1935, but passenger service required bigger and better aircraft. Accompanied by much fanfare, the Martin M-130 was introduced in 1936, followed by the Boeing 314 in 1939. Known as Pan Am Clippers, these mammoth flying boats flew from San Francisco harbor skipping across the Pacific with stops at Hawaii, Midway Island, Wake Island, Guam, the Philippines and then Hong Kong. Advance teams had prepared the stopover islands by blasting coral to make safe coves for sea landings and constructing luxury hotels for Pan Am’s discerning, rich clientele. Next on the Pan Am list for conquest was the world’s other major ocean – the Atlantic.The Boeing 314 entered European service in 1939 flying from New York to Lisbon and Marseille by way of the Azores.

Boeing 314

As airplane travel became popular during the mid-1930s, passengers wanted to fly across the ocean, so Pan American Airlines asked for a long-range, four-engine flying boat. In response, Boeing developed the Model 314, nicknamed the “Clipper” after the great oceangoing sailing ships.

The Clipper used the wings and engine nacelles of the giant Boeing XB-15 bomber on the flying boat’s towering, whale-shaped body. The installation of new Wright 1,500 horsepower Double Cyclone engines eliminated the lack of power that handicapped the XB-15. With a nose similar to that of the modern 747, the Clipper was the “jumbo” airplane of its time.

The Model 314 had a 3,500-mile range and made the first scheduled trans-Atlantic flight June 28, 1939. By the year’s end, Clippers were routinely flying across the Pacific. Clipper passengers looked down at the sea from large windows and enjoyed the comforts of dressing rooms, a dining salon that could be turned into a lounge, and a bridal suite. The Clipper’s 74 seats converted into 40 bunks for overnight travelers. Four-star hotels catered gourmet meals served from its galley.

Boeing built 12 Model 314s between 1938 and 1941. At the outbreak of World War II, the Clipper was drafted into service to ferry materials and personnel. Few other aircraft of the day could meet the wartime distance and load requirements. President Franklin D. Roosevelt traveled by Boeing Clipper to meet with Winston Churchill at the Casablanca conference in 1943. On the way home, President Roosevelt celebrated his birthday in the flying boat’s dining room.

Sikorsky S-42

The Sikorsky S-40 had laid the groundwork for Pan Am’s Latin American route system, but Pan Am was never fully satisfied with its compromise design,. Even before the S-40 first entered service, Pan Am technical adviser Charles Lindbergh was developing specifications for a streamlined airliner that could truly span the oceans and fulfill Pan Am’s intercontinental ambitions.

Two aircraft manufacturers made credible bids for Pan American’s next airliner. Igor Sikorsky wanted the chance to build improve the S-40, whose limitations he fully understood, and Glenn Martin wanted to expand his business from military to commercial aircraft. To hedge his bets against either company’s possible failure, and to stimulate competition, so that Pan Am would not be overly dependent on any one firm, Juan Trippe accepted both bids and ordered three planes from each company. On October 1, 1932, Pan Am placed a firm order for three S-42 aircraft, with an option for seven additional planes.

Martin M-130

Even before the first Sikorsky S-40 entered service in 1931, it was obvious that the plane — which Charles Lindbergh called a flying forest — would not provide the performance necessary to fulfill Pan Am’s ambitions. Consequently, the airline began searching a streamlined airliner that could truly span the oceans. Two manufacturers wanted the job. Igor Sikorsky wanted a chance to improve on his own S-40, and Glenn Martin wanted to establish his company in the commercial aviation business. Juan Trippe ordered planes from both.

The driving force behind Pan Am’s specifications for a new plane was Andre Priester, the Dutch immigrant who had worked for KLM and who became Pan Am’s detail-obsessed chief engineer. Charles Lindbergh, who had been so deeply involved with Pan Am’s earlier designs, had just undergone the trauma of his son’s kidnapping and murder on March 1, 1932, and was only minimally involved with the plans for the new clipper.

Pan Am wanted a plane that could fly 3,000 miles (long enough to reach Europe or Hawaii) while carrying a payload equal to its own weight, and the Glenn L. Martin Aircraft Company designed a plane that met the airline’s needs. Although the first Martin M-130 was delivered over a year behind schedule, and its $417,200 cost was almost twice that of the Sikorsky S-42 (and more than five times the $78,000 price of the leading airliner of the day, the Douglas DC-2), the M-130 had the speed, size, and range to carry mail and passengers profitably across the Pacific or Atlantic.

The first M-130, named China Clipper, was delivered to Pan American on October 9, 1935, just two days after its first test flight. A little more than a month later, on November 22, 1935, China Clipper left San Francisco on the first scheduled mail flight across the Pacific ocean.

Below are a few pictures of Clippers. These were borrowed from Holcomb’s Aerodrome located at www.airminded.net Great website for all of us aviation enthusiast–take a look.

The Golden Years and Technology

Part Four – The Boeing 707 – June 26, 2009

Quote of the Week

“After about 30 minutes I puked all over my airplane. I said to my self, “Man, you made a big mistake.”—Charles ‘Chuck’ Yeager regards his first flight

The Boeing-707

Before we begin with the 707, let’s look again at where we have come from in this series. The Boeing-247 set the stage for air travel as we know it and the DC-3 took it to the next level. Transcontinental flights were now a daily occurrence, more and more communities were being added and served on a daily basis, and operational safety was improving. The Clippers opened up the door for international travel and blazed a trail for other international carriers to follow and then as piston engine design hit its limit World War 2 provided new technology. Now, forward in to the jet age and the Boeing-707.

The Boeing 707 was to become the first turbine-engine powered airliner in the United States. The basic design was derived from the Boeing 377 Stratocruiser as the B-47 bomber. So pure was the design of the Boeing 707 that it has served as the basis for all future Boeing transports to the current day as well as those of its rivals. By the time production finally ended in 1991 there had been 1,010 aircraft built for passenger, freight, and military operations.

The 707 had seating for approximately four times as many passengers as its closest rival, the British De-Havilland Comet, as well as a higher maximum speed. These basic points, combined with a structural problem of the British aircraft that led to a number of well publicized accidents, helped establish the 707 in World-Wide service. The British returned to the skies in 1958 with the Comet-4 and were the first to open a transatlantic passenger jet service. However, Pan Am inaugurated the first round-the-world jet passenger service on October of 1959.

The first commercial 707s, labeled the 707-120 series, had a larger cabin and other improvements compared to the prototype. Powered by early Pratt & Whitney turbojet engines, these initial 707s had range capability that was barely sufficient for the Atlantic Ocean. A number of variants were developed for special use, including shorter-bodied airplanes and the 720 series, which was lighter and faster with better runway performance.

Boeing quickly developed the larger 707-320 Intercontinental series with a longer fuselage, bigger wing and higher-powered engines. With these improvements, which allowed increased fuel capacity from 15,000 gallons to more than 23,000 gallons, the 707 had truly intercontinental range of over 4,000 miles. Early in the 1960s, the Pratt & Whitney JT3D turbofan engines were fitted to provide lower fuel consumption reduce noise and further increase range to about 6,000 miles.

There is a lot of information on the 707 readily available on the web and a good start point is the Boeing web site, http://www.boeing.com/commercial/707family/index.html, where I have spent many hours researching different airplanes.

Below are a couple photos of the Boeing 707 chosen from open sources on the web.

Thanks for stopping by and letting me be a part of your week. Remember those who are following in your/our footsteps need your help. Take care, keep friends and family close and fly safe.

Robert Novell

July 5, 2013