The Plane and The Iron Horse – (Part Two) – September 27, 2013

The Plane and The Iron Horse – September 20, 2013

September 19, 2013The Plane and The Iron Horse – Part Three – October 4, 2013

October 4, 2013“Robert Novell’s Third Dimension Blog”

Good Morning—I hope everyone had a good week, and will have an even better weekend, but if you have to work then be safe/fly safe. Time to talk aviation history again and today we have Part Two of the story on TAT. If you missed last weeks blog click here.

Enjoy…………………..

TRANSCONTINENTAL AIR TRANSPORT, INC.

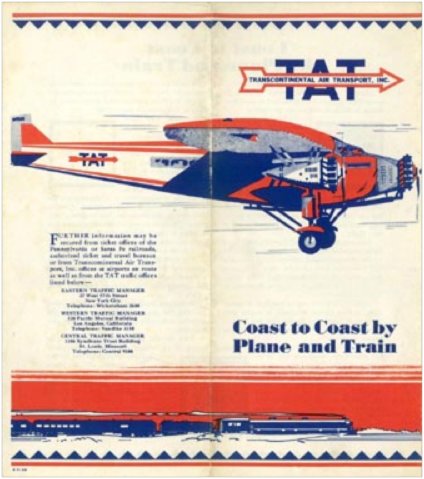

Thus TAT was certainly no flash-in-the-pan outfit. It had the resources to purchase ten of Ford’s mammoth Trimotors, each of them named after cities in the manner of locomotives, and to equip them with luxuries unheard of in that day: radios, in-flight attendants, lavatories, and kitchens. Furthermore, the service was inaugurated on a wave of press-agentry. The first trip eastbound from Los Angeles, on July 8, 1929, was piloted partway by Lindbergh himself. The new Ford plane was christened “The City of Los Angeles” by popular film star Mary Pickford. Whirring newsreel cameras and gawking spectators did not obscure the real significance of the flight, which was that even with the nighttime rail links included, the combined time bettered the all-rail time by twenty-four hours. “For those whose time is too important to waste” was the way TAT advertised itself.

For the typical westbound TAT passenger that summer the trip began at 6:05 P.M. at Pennsylvania Station in New York City, where he boarded the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Airway Limited, a luxury Pullman, for the first leg of the journey across the Alleghenies. The overnight train ride avoided the mountainous region veteran air-mail pilots called “Hell Stretch,” where winds were adverse, the weather subject to sudden change, and aside from a few small fields like Bellefonte in Pennsylvania there was almost no place to land. The only inconvenience to the train ride was the baggage restriction: thirty pounds per passenger.

The first stop the next morning was Port Columbus, a specially built air-rail facility outside Columbus, Ohio— the only one of its kind in the world. There the TAT traveler passed through a briskly efficient ticket confirmation, then walked out the airfield side of the Station under a luxurious orange and black striped canopy to a waiting Ford Trimotor. The aircraft stretched seventy-four feet from wing tip to wing tip. Its massive engines—as the copilot explained at a preboarding briefing—would sustain flight if only two were functioning; with only one engine the plane could maintain a long, slow glide that would enable the pilot to find a suitable emergency landing field. Thus reassured that parachutes were unnecessary (the question inevitably arose in those days), the passenger enplaned as an attendant rather self-consciously announced: “All aboard by air for Indianapolis, St. Louis, Kansas City, and points west.”

Once on board, the passenger was greeted by another attendant, who introduced himself by name as the inflight cabin steward. These attendants were selected by TAT for their clean cut college-boy good looks (flying was considered a man’s work in those days), and they lavished attention on the passengers. There were five wicker seats arranged along each side of the Ford, with a narrow aisle up the center. Each had a seat belt and was elegantly appointed, with a small window next to it draped in brown velvet curtains. There was even an individual reading lamp, with parchment shade, and an individual electric cigar lighter with ashtray. The cabin was a rhapsody of brown and gold lacquered surfaces.

The pilot was already in the cockpit, his head and shoulders visible through the half-partition separating the passenger cabin from the flight-control area. He was usually a man in his mid-thirties who was being paid up to twelve thousand dollars a year. The airline had adopted the policy of uniforming its flight personnel, giving them the titles “captain,” “first mate,” and “steward” in order to borrow the reputation for solid dependability those terms suggest. Furthermore, TAT encouraged its captains to mix with the passengers (though not in flight), and it was official company policy to have the pilots debunk the image of youthful daredevilry that the public then associated with flying. One method of accomplishing this was to have the pilots joke about their age by saying: “There are old pilots and there are bold pilots—but there are no old, bold pilots!”

For newcomers to aviation the takeoff was always exciting. A muffled shout came from the cockpit: “Clear!” First one, then the other two engines, in rapid succession, clanked, shuddered, popped, and sputtered to a full, even-throated life. The noise was loud and got worse as the pilot opened the throttle and eased the Ford toward the warm-up area.

Once there, the pilot braked the plane abruptly about into the wind and commenced checking out each engine individually by running up to high power. The roar, merely unpleasant at first, became so deafening that the cabin attendant passed out balls of cotton to stuff in the ears. A Very pistol was discharged, and its green fireball, arcing up from the distant terminal building, signaled the all clear for takeoff. The plane began moving to a crescendo of noise and vibration. Bump, bump, the tail was up; a few more bumps on the two main wheels and the craft was airborne. After a climb to an altitude of about 2,500 feet, the plane leveled off, the engine noise decreasing somewhat as the pilot retarded the throttle. Cruising at about 100 miles an hour, a westbound plane maintained a relatively low altitude in order to stay below strong head winds higher up (on the eastbound route the pilot flew higher to take advantage of the velocity of the prevailing westerly).

Once the plane was airborne, the steward passed out small aluminum trays bearing coffee, rolls, and small bottles of milk. The serving ware was a specially designed lightweight service called dirigold.

At 10:00 A.M., after a two-hour flight, the plane arrived over Indianapolis and commenced a slow descent toward the turf landing field on the southwestern outskirts of the city. Another green fireball arced upward, clearing the pilot to land.

After deplaning at the spanking-new terminal, which housed a telegraph office and a small but elegant dining room, passengers had a few minutes to walk about and send messages while a swarm of TAT linemen pumped gasoline into the Ford and performed other routine checks, often to an audience of curious onlookers. The terminal building also contained a weather-reporting station, one of a nationwide network of seventy-two observation and reporting stations recently established by the Department of Commerce.

The Ford Trimotor had a fuel capacity sufficient to sustain altitude for nearly six hours, but TAT scheduled stops every 250 miles or so, partly because this increased the margin of safety in case of emergency and partly because there was a logical spacing of cities at about that interval throughout the Midwest, thus increasing the possibility of developing a profitable intercity passenger service. Accordingly, after Indianapolis the next stop was St. Louis, a harrowing landing over several houses and two high-power electric lines onto a narrow asphalt strip.

During the short ground period a sandwich lunch was brought aboard to be served en route to Kansas City, a three-hour Might away. The tedium of this leg of the journey was often broken by allowing the passengers to peek at the cockpit over the pilot’s shoulder—as long as they did not speak to or otherwise distract him. The cockpit was somewhat narrower than the rest of the airship, crowded with a bewildering array of gauges, dials, levers, and switches. There was a periscope through which the pilot could observe the tail assembly for signs of ice accumulation or mechanical malfunction. Unlike the single- and two-seat planes of that era, which had control sticks for steering, the Trimotor had two steering wheels, one for the pilot and one for the copilot.

After an uneventful stop in Kansas City, whose airport was much like the others, the plane continued to the southwest toward Wichita, a short leg of less than two hundred miles but one often subject to turbulence, The remedy for airsickness then was slices of lemon, handed out by the accommodating steward, though frequently passengers just opened their windows for a breath of fresh air. For those who could not stomach continuing, a train could always be taken, because the flight path followed roughly the route of the Santa Fe Railroad from Kansas City to Los Angeles.

The day’s air travel ended about 7 P.M. on a prairie field four miles east of remote Waynoka, Oklahoma. Waynoka was chosen because it was just a day’s flying time from Port Columbus. The town numbered barely twelve hundred souls, but its selection for the TAT system engendered a wild little speculative boom, local townspeople expecting to become rich by purchasing the empty pastureland surrounding the TAT field. Despite the modern look of TAT’S new terminal, however, it was an unpromising place, stranded in the midst of parched semi desert.

A small but luxuriously upholstered trailer bus, called an Aero Car and manufactured for TAT by General Motors, carried passengers into Waynoka proper on a gravel road. There, shortly before 9 P.M. and after dinner in a special TAT Harvey House restaurant at the train station, they boarded a luxury-class Pullman for the nighttime trip across the Texas panhandle. It arrived at 6 A.M. in Clovis, New Mexico, where passengers were conveyed by Aero Cars five miles outside of town to the adobe TAT airport dubbed “Portair, New Mexico” for breakfast and an 8 A.M. flight to Albuquerque. The Waynoka-to-Clovis rail link was to be eventually eliminated once the government beacon light system went into operation. These beacons, to be positioned at regular intervals along the route of flight, would allow the pilot to follow a winking series of lights in the darkness, and were similar to, though smaller than, the 2,000,000-candlepower “Lindbergh Beacon” already in use atop the Palmolive Building in Chicago.

Next week we will continue with Mr. Hopkins so be sure you on stop by for the conclusion of our story.Until next time remember that all aviators are “Gatekeepers of the Third Dimension.”

Robert Novell

September 27, 2013